Palaeontologists re-examine a 200-million-year-old fossil from Greenland, reigniting debate about the origins of mammals

How old are you? What if, when someone asked you this question, you answered with the age of all humans? 2.3 million years, you would say. What about all primates? Around 80 million years old. If you wanted to answer for the whole of mammal-kind, you’d find the answer depends who you ask.

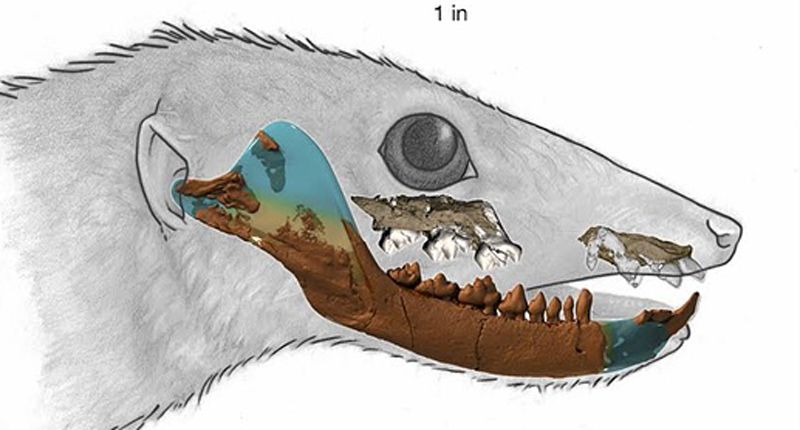

In November a new paper came out that stirred an ongoing debate among palaeontologists working on the first mammals and their close relatives. Early-mammal expert Professor Zhe-Xi Luo, from the University of Chicago, led a team reanalysing the fossil of a mouse-sized creature called Haramiyavia clemenseni using CT-scans . They found anatomical details that appear to push this little beastie out of the bushy crown of the mammalian tree, relegating it to the side branches. This has big implications for the age of all mammals.

Related: What if the story of life on Earth isn't what you think it is?

One thing that really gets an early-mammal researcher talking is the question: what is a mammal? Any seven-year-old could answer this about the lions, elephants and armadillos alive today, but rewind 230 million years to the Triassic and things get trickier. If we had a time machine, we could send the BBC natural history unit back with their film equipment to create a stunning documentary showing us whether these ancient ancestors laid eggs, produced milk, or had full coats of fur. Along with them, a scientist could extract some blood and use genetics to tell us who is related to who, and how closely. For now though, we can only rely on fossils to provide evidence. We must examine their petrified skinless skeletons for clues about when mammal-like reptiles became actual mammals.

Palaeontologists class early mammals as either mammaliformes, or crown mammals. The mammaliaformes are mammal-like, but not quite mammals. The crown mammals are considered mammals and include our ancient relatives, alongside a plethora of extinct brothers and sisters. Slight changes in anatomy – such as different grooves in the jaw and the development of the inner ear bones - indicate to palaeontologists whether these creatures are more closely related to later mammal groups. Whether the haramiyidans – the group that includes the re-described Haramiyavia clemenseni specimen – are crown mammals or not, has divided expert opinion.

Haramiyidans were originally identified from individual teeth scattered randomly through the Triassic rocks of Europe . Scientists couldn’t figure out how the teeth fit into a jaw, and without that information, assessing where they fit in the mammal tree was difficult. Researchers suggested they were related to another extinct group of mammals called multituberculates (named for the multiple knobbles on their teeth) who shared some of their dental characteristics.

In time, more haramiyidan specimens emerged, including H. clemenseni from the frozen rocks of Greenland. This comprised teeth set into a jaw, as well as some pieces of the body skeleton. For a long time it was the most important fossil in the debate about haramiyidans. A team led by the late palaeontologist Farish Jenkins used it as evidence to place the haramiyidans right at the base of crown Mammalia , arguing that although the little animal’s teeth were distinctly different from other early mammals, it was indeed an early crown mammal, and had the jaw grooves to prove it. Others said the grooves necessary to diagnose H. clemenseni as a crown mammal were missing and inconclusive - it was probably only a mammaliaform.

Why, you may be wondering, does it matter if this little mouse-thing* was a crown mammal or not? It makes all the difference for the timing of our mammal origins – the age of us.

The haramiyidans first appear in the late Triassic – H. clemenseni is one of the oldest found so far. If it is a crown mammal, this pushes our common ancestor right back into the Triassic. It means mammals survived not only the end-Cretaceous extinction that killed off the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, but also the end-Triassic extinction 200 million years ago. This lesser known extinction event wiped the decks clear and allowed dinosaurs to dominate the earth.

However, if the haramiyidans are not crown mammals, and are instead just close relatives, then mammals have their origins much later, in the Jurassic. Such details are important to scientists studying macro-evolution; large scale patterns of life on earth and the forces that drive them. Lots of new creatures emerged in the early Jurassic as life recovered from the end-Triassic mass extinction, so if mammals appeared at this time it would make sense. However, if crown mammals diversified before the extinction event, this raises questions about what drove their evolution. It may not sound like a big deal, but the time difference in crown mammal origins is about 30 million years. To put that into perspective, the primates that would become humans split away from our common ancestor with chimps about 7.5 million years ago. Geologically it seems trivial, but a lot can happen in 30 million years.

Related: Extinct thinking: was the hapless dodo really destined to die out?

Haramiyidans are one of many enigmatic beasts to emerge from new fossil beds in China. Specimens like Arboroharamiya jenkinsi from the Tiaojishan Formation , described by a team led by palaeontologist Xiaoting Zheng of Linyi University in Shandong, are stunningly complete, giving us a whole body to work with for the first time, and a wealth of new anatomical data to argue over. Just last year three more amazingly complete haramiyidans from the same rock formation were the basis of a fresh argument by Shundong Bi (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and colleagues that these creatures are crown mammals after all, related to multituberculates as previously suggested, and that the common ancestor of all crown mammals was, indeed, 30 million years older in the late Triassic.

And so the argument continues. Last month’s paper is the most recent in a line of contributions to scientific knowledge. It uses the latest techniques to update the discussion: reconstructing that battered H. clemenseni jaw from Greenland using x-ray computed tomography – the same CT scanning carried out in hospitals to see inside the human body. This is something the early palaeontologists could never have dreamed of when they tried to stick those first fiddly haramiyidan teeth together over 100 years ago.

Until that time machine becomes available, teams of palaeontologists will use complex dental arrangements and the placement of jaw grooves in fossils to try and determine just how long ago our last common ancestor scurried away from the rest of the mammaliaformes to become the first “true” mammal. We will continue to write new pages in the story of us.

*mouse-like, but rodents didn’t exist for another 140 million years.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2015