The Moon might be older than scientists previously thought

A physicist, a chemist and a mathematician walk into a bar. It sounds like the start of a bad joke, but in my case, it was the start of an idea that could reshape how scientists think about the history of the Moon.

The three of us were all interested in the Moon, but from different perspectives: As a geophysicist, I thought about its interior; Thorsten Kleine studied its chemistry; and Alessandro Morbidelli wanted to know what the Moon’s formation could tell us about how the planets were assembled 4.5 billion years ago.

When we got together to discuss how old the Moon really was, having those multiple perspectives turned out to be crucial.

How did the Moon form?

At a conference in Hawaii in the late 1980s, a group of scientists solved the problem of how the Moon formed. Their research suggested that a Mars-size object crashed into the early Earth, jettisoning molten material into space. That glowing material coalesced into the body now called the Moon.

This story explained many things. For one, the Moon has very little material that evaporates easily, such as water, because it began life molten. It has only a tiny iron core, because it was mostly formed from the outer part of the Earth, which has very little iron. And it has a buoyant, white-colored crust made from minerals that floated to the surface as the molten Moon solidified.

The glowing, newly formed Moon was initially very close to the Earth, at roughly the distance that TV satellites orbit. The early Moon would have raised gigantic tides on the early Earth, which itself was mostly molten and spinning rapidly.

These tides took energy from the Earth’s spin and transferred some to the Moon’s orbit, slowly pushing the Moon away from the Earth and slowing the Earth’s spin as they did so. This motion continues today – the Moon still recedes from the Earth about 2 inches per year.

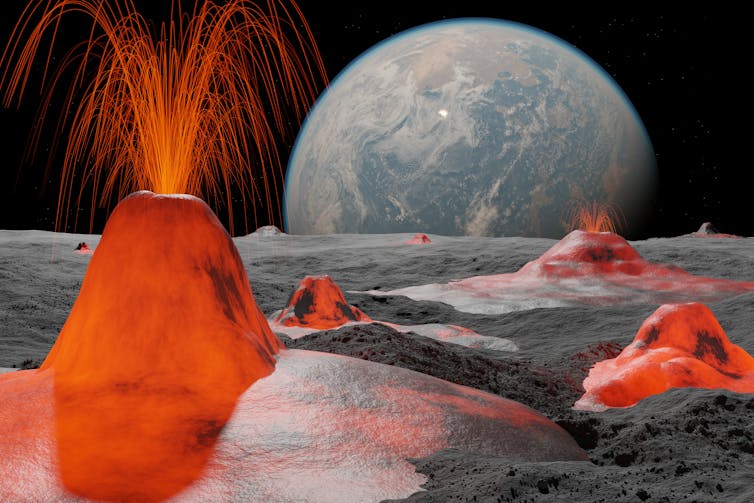

An artist’s impression of what the Moon looked like during the tidal heating event. There would have been intense volcanism everywhere. The early Earth would have loomed much larger in the sky because it was closer. MPS/Alexey Chizhik

As the Moon moved away, it passed through particular points where its orbit temporarily became disturbed. These orbital disturbances were an important component of its history and are a key part of our hypothesis.

When did the Moon form?

When the Moon actually formed and receded away from the Earth is a thorny issue.

Thanks to the Apollo astronauts, scientists have a collection of Moon rocks, which they can measure the age of. The oldest rocks are all about 4.35 billion years old, which is roughly 200 million years after the birth of the solar system.

Many geochemists, like my colleague Thorsten Kleine, suggested (not unreasonably) that the age of these rocks is the same as the age of the Moon.

But people like Alessandro Morbidelli, who study planet formation, didn’t like this answer very much. In their models, planets swept up most of the material floating around the early solar system long before 200 million years had elapsed. A giant, Moon-forming impact as late as the rock samples suggested seemed pretty unlikely.

What did we suggest?

This is where Kleine, Morbidelli and I came in. We followed up on a suggestion from a 2016 study that found the Moon might occasionally experience extreme heating events during its slow outward journey from Earth.

This heating happens the same way that heating does on Jupiter’s hyperactively volcanic moon Io. The smaller body’s shape gets squeezed and stretched by tides from the big body. And just like a rubber ball warms up if you squeeze it enough, so too do the rocks on Io and the Moon.

All rocks contain little internal clocks – radioactive elements that decay and allow researchers to tell how old the rock is. But here’s the key point: If the Moon warmed up enough, its clocks would lose their memory and would start recording time only once the Moon cooled down again.

So in this picture, the pileup of rocks aged around 4.35 billion years isn’t telling us when the Moon formed, but just when it went through this tidal heating event. That means the Moon’s formation must have happened earlier.

An early formation date satisfies the physicists studying planet formation, while explaining that the later dating recorded from the rocks is due to the tidal reheating.

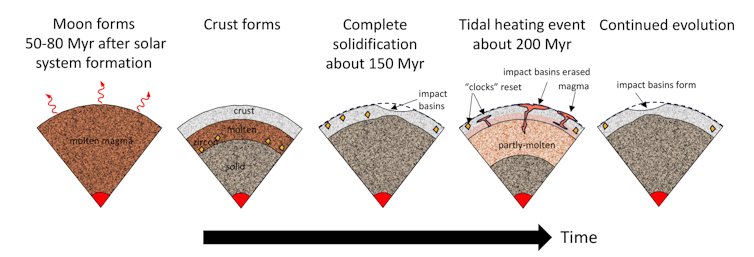

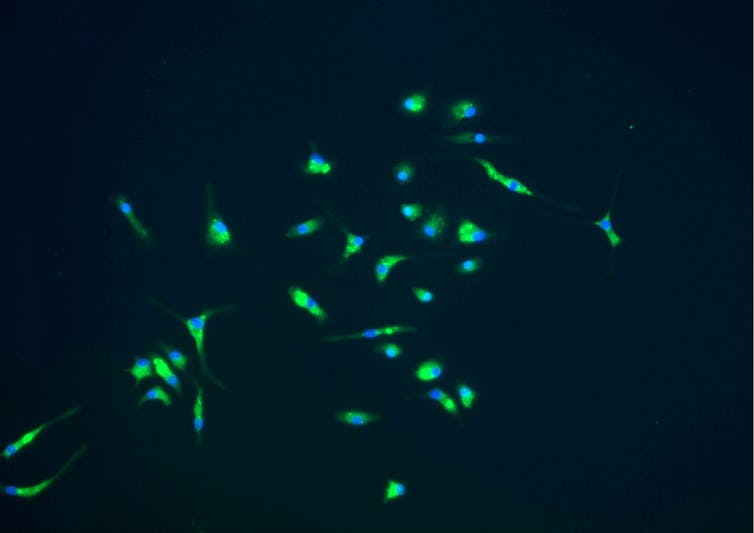

The Moon started out molten and then cooled down, only to be reheated roughly 100 million years later. This heating event could have reset most of the ages recorded by lunar rocks. Francis Nimmo

What next?

As often happens in science, two groups simultaneously came up with a similar idea. Our group focused on a tidal heating event that happened when the Moon was quite distant from the Earth, while research from Steve Desch at Arizona State University points to an event that happened when the Moon was closer. Sorting out which of these two hypotheses is right will take some time – and maybe neither is correct.

Testing these hypotheses will require more samples from the Moon. Fortunately, China’s Chang’e 6 mission just returned samples from the dark side of the Moon in June 2024. If these samples also show a lot of rocks all having ages of around 4.35 billion years ago, that would be consistent with our story. If the ages are much older, we’ll have to figure out a new story.

Very often in earth and planetary sciences, geochemists and geophysicists end up with different and contradictory hypotheses. This happens partly because these fields use different kinds of measurements, but also because they speak very different scientific languages. Overcoming this language barrier is hard.

Our study is an example of how – sometimes – bridging that linguistic and scientific divide can benefit researchers on both sides.![]()

Francis Nimmo, Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.