Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba boarded a yacht off the coast of Florida with the top prosecutor in charge of fighting crime in his city and several rowdy out-of-state men who said they wanted to drop millions revitalizing downtown.

Lumumba, who is running for reelection in 2025, had planned to wear his normal suit and tie during this fundraising trip to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the mayor’s spokesperson said, but the men assured him it was a casual affair. He opted for dark jeans and a black button-up.

As they cruised through the Atlantic on a boat stocked with expensive booze in April, the supposed developers were angling to arrange a deal between Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens and the mayor.

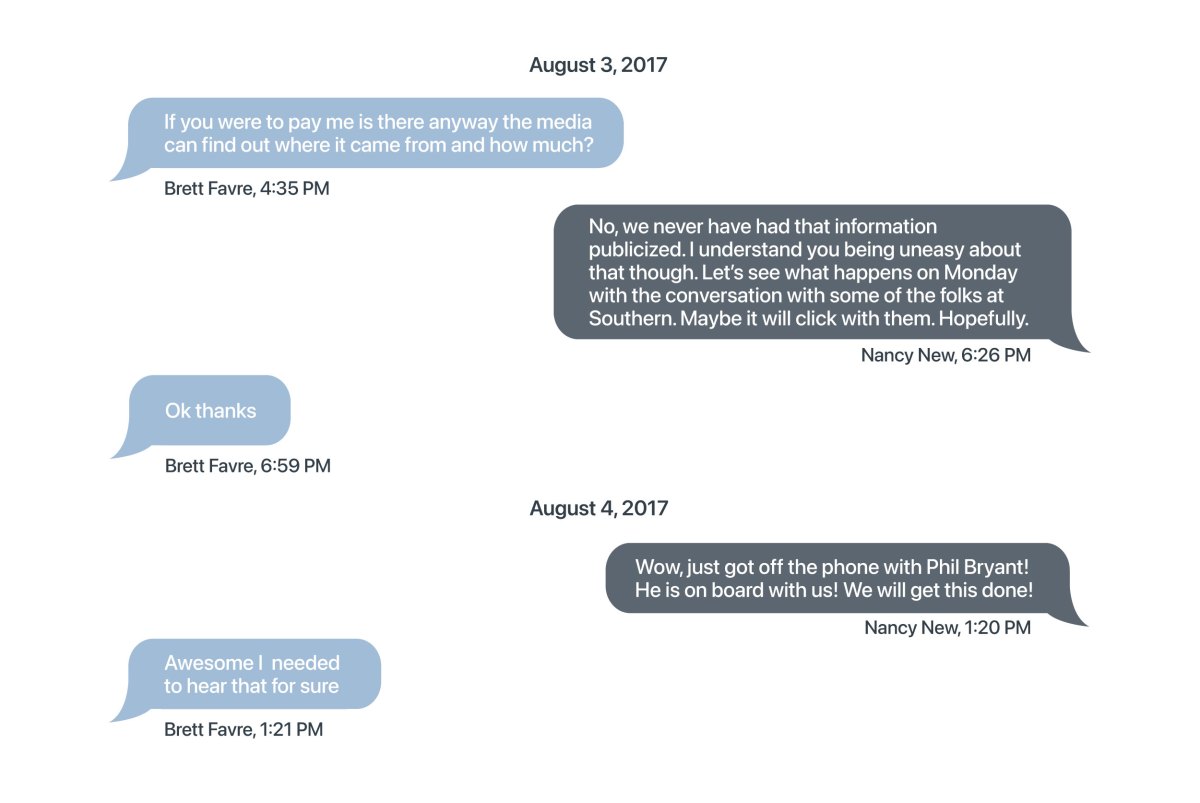

The investor group, known as Facility Solutions Team, had given Owens $50,000 that he divvied up into campaign checks to Lumumba from multiple donors.

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens

Owens, who moonlights as a businessman and consultant, had been working for the company since the previous year to entice local officials to support their proposal for a long-welcomed downtown hotel complex in the capital city.

Liquor flowed at Owens’ downtown tobacco lounge where the men first met and regularly spent time in a room hidden behind a bookcase door. A video shows one of the gregarious real estate moguls dancing to club music at the well-lit, nearly empty bar. In Miami, the developers took the mayor and district attorney to a 76,000-square-foot “full nude” cabaret called Tootsie’s and indulged in evening cigars.

But the high-rollers weren’t who they appeared to be. They were FBI agents and an informant using a familiar playbook — masquerading as the same Goodfellas-esque characters, flaunting the same yacht and dropping thousands of taxpayer funds at the same strip club — they’ve used to bust public officials in other cities. One of the undercover cops was publicly condemned by the FBI for having a sexual relationship inside a Cincinnati penthouse suite that the government rented as part of their sting there, according to news reports.

By the time Lumumba and Owens took the sunset cruise, the city had already opened a bid soliciting information from prospective developers for the downtown project. According to the feds, the mayor could help them by shortening the time to respond, hopefully hurting the competition.

From the yacht, Lumumba made the call to change the deadline. One of the undercover agents handed the mayor the campaign checks while they were still on the boat, prosecutors allege.

A few days later, prosecutors alleged Lumumba took out nearly $15,000 of that by writing checks from his campaign to himself and cashing them.

Federal indictments against Owens and Lumumba unsealed Thursday accuse them of several counts including conspiracy, bribery, racketeering, wire fraud and money laundering — some of which come with possible sentences up to 20 years. Owens is also accused of making false statements to the FBI.

Lumumba announced the indictment Wednesday before it was unsealed, denying the allegations and calling the case “political prosecution.” They both pleaded not guilty Thursday.

The agents were drawn to Mississippi’s capital as early as December of 2022 after years of suspected corruption among its leaders. And they recorded.

“I don’t give a shit where the money comes from. It can come from blood diamonds in Africa, I don’t give a fucking shit,” Owens said, according to the indictment, during one of their raucous meetings at his cigar shop. “I’m a whole DA.”

“We can take dope boy money,” he added, “... but I need to clean it and spread it.”

Outside the federal courthouse Thursday, Owens described his quotes in the indictment as “cherry-picked,” and, echoing President-elect Donald Trump’s rationale for his reported vulgarity from 2016, “drunken, locker room banter.”

Jackson City Council member Aaron Banks, who allegedly took cash bribes and favors in exchange for his future vote on the development, also pleaded not guilty in the case on Thursday. He did not speak with reporters.

READ MORE: The full indictment against Owens, Lumumba, and Banks

Another city council member Angelique Lee was the first to resign and plead guilty in August to her part in the scheme, including a $6,000 FBI-funded shopping spree for, among other things, Valentino sandals and a Christian Louboutin tote bag. Owens’ cousin and business associate, Sherik “Marve” Smith, also pleaded guilty in October to acting as a go-between for the district attorney with both Lumumba and Banks.

This kind of political corruption not only erodes public trust, it “hampers economic development and further exacerbates inequality,” according to global anti-corruption coalition Transparency International.

When officials choose contracts with companies based on bribes and kickbacks rather than fair competition, it can increase the costs and reduce the quality of basic services and goods. In communities already facing high poverty, which are more susceptible to corruption, people “don’t necessarily have time to hold their government to account because they don’t have the resources or the ability to do so,” said Transparency International researcher Caitlin Maslen.

“So it just further drives their vulnerability, and of course, at the end of the day, the people who are benefitting from that are corrupt public officials,” Maslen said.

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens (right) addresses a question as Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (left) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023, in Jackson.

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens (right) addresses a question as Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (left) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023, in Jackson.

Jackson has made national headlines in recent years for its crumbling infrastructure, which Lumumba largely inherited when he took office in 2017 and has left residents without clean water — or sometimes without water at all — at their faucets.

Partly to blame was a highly political and badly bungled $90 million water billing and meter installation contract with German-based manufacturer Siemens signed a decade earlier, and the city got its money back through a court settlement in 2020. But the lawyer, one of Lumumba’s top political donors, took $30 million of that.

The Capital City caught the eye of federal authorities during a years-long conflict between the mayor and council starting in 2021 over selecting a garbage collection vendor, resulting in recurring emergency contracts.

Once in the spring of 2023, residents didn’t see their trash picked up for 17 days.

The mayor lobbed bribery allegations against council members to explain the stalemate and the FBI reportedly examined the ordeal.

If federal criminal investigators gathered evidence of corruption related to the garbage procurement or the other attention-grabbing snafus in city government in recent years, they haven’t released it to the public.

Instead, the FBI decided to concoct its own bribery scheme.

The agents found an obvious weakness: The city’s desire to build a hotel complex downtown on Pascagoula Street on three empty parcels across from the 15-year-old convention center — a long running saga of questionable characters, financial miscalculations and bidding missteps.

Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024.

Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024.

In a separate investigation, the FBI had already found that Jackson’s previous mayor took $80,000 in donations and gifts from a contractor who bid on the same project, according to transcripts from a 2022 trial in Atlanta. They never charged him.

Getting Owens to partner with FST, their development front, proved crucial to the undercover agents’ plan. Owens bragged to them that he and his cousin “‘own enough of the city’ and that he had ‘a bag of fucking information on all the city councilmen’ that allowed him to ‘get votes approved,’” according to the indictment.

The district attorney and mayor, both Democrats, have a friendship. Owens lent an air of credibility to the undercover scheme that without, local politicians may have never entertained the men.

At a Feb. 12 dinner Owens arranged to introduce Lumumba to his partners, the district attorney said, “I’ve done background checks. They’re not FBI by the way,” according to the indictment.

To secure indictments, the agents had to provide the officials a benefit — whether cash, fancy clothes, a job for a family member, a private driver, or simply a campaign contribution — and record them agreeing to take some official act, however insignificant to their company actually securing a deal with the city.

In late March, Owens and the agents took Lee, who represented northwest Jackson on the city council, out to dinner at Pulito Osteria Italian restaurant in Belhaven. As they were leaving, one of the agents handed Lee a bag of $3,000 in cash. “Oh my god,” Lee said, according to a recording transcript read in court. “... I’m not reporting this.”

“I mean it’s cash, why would you report it? Don’t report it,” the FBI agent responded, then thanked Lee for her support for their project.

“You’ve got more votes coming,” she responded. “I’ll make sure of that.”

In Lee’s case, she admitted to agreeing to approve closing a small portion of Farish Street between two city parcels so the developers could build on top of it — a vote that was not then actually slated to come before the council. Lee also agreed to approve the actual development proposal, which would also have occurred several steps ahead in the process.

To ensnare the mayor, who does not vote on development projects, the agents exercised some creativity in establishing an official act. They asked Lumumba to close the deadline to respond to the city’s procurement two weeks earlier than planned under the guise that, prosecutors allege, it would exclude their competition — though two other firms managed to squeak through their proposals just in time, according to public records.

The indictment includes a photo from the yacht of the mayor, sitting next to Owens, talking on his phone to his city planning director.

A photo included in the federal indictment shows Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, left, talking on the phone while sitting with Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens on the yacht.

A photo included in the federal indictment shows Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, left, talking on the phone while sitting with Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens on the yacht.

The city never selected FST as the winning proposer and the council never took a vote on the project — not that it mattered for the purpose of charging the officials.

“It’s a broad statute … Under the conspiracy statute, (the crime is) doing an official act in exchange for some type of benefit, and it’s the contemplation of doing it in exchange for that benefit,” said attorney Aafram Sellers, who represented Lee through her guilty plea. “The fact that it wasn’t imminent that they were going to do it doesn’t matter.”

Weeks after the alleged bribes were delivered, the FBI raided Owens’ businesses and the district attorney’s office, where they found $20,000 in cash hidden in a lockbox disguised as a book titled, “The Constitution of The United States of America,” according to the indictment. They also seized phones from the mayor and the two city council members.

The FBI found $20,000 in cash hidden in a lockbox disguised as a book titled, “The Constitution of The United States of America,” according to the indictment.

The FBI found $20,000 in cash hidden in a lockbox disguised as a book titled, “The Constitution of The United States of America,” according to the indictment.

The investigation has been a slow burn in the months since, with the feds waiting until just after the presidential election to snag the big fish.

In cases where there’s evidence a public official has taken a direct personal benefit, such as cash or expensive gifts, in exchange for some official action, the government’s case for bribery is typically a slam dunk.

In Cincinnati, the federal government secured a conviction and two-year prison sentence for Cincinnati City Council member Jeff Pastor after he allegedly took $55,000 in bribes, much of it cash. Testimony in that case revealed that the agents also took Pastor to Miami and, like they did for Owens and Lumumba, treated him to expensive liquor, a yacht cruise and Tootsie’s Cabaret.

But when the only benefit to the official is a campaign contribution, a fine line exists between bribery and plain old politicking — especially in a political environment fueled by lax campaign finance requirements and a robust lobbying industry.

And in some cases resulting from these same FBI stings elsewhere, the criminality hasn’t been so clear.

Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, whom the undercover agents attempted to bribe with tickets to the broadway show Hamilton, was acquitted last year on one charge of lying to the FBI. A judge dismissed several other charges alleging he promised city contracts in exchange for donations during his 2018 run for the governor of Florida, according to POLITICO.

Cincinnati Councilman Alexander “PG” Sittenfeld, who was convicted last year of taking $20,000 in campaign contributions in exchange for his support of a development project in a nearly identical FBI sting, was released from prison early in May — a rare occurrence — after the court found his appeal raised a “close question” about his guilt.

Though agents recorded Sittenfeld saying questionable things like, “I can move more votes than any single other person,” he argued there was no evidence his future vote or lobbying effort was predicated on him receiving the donation. This exchange — what’s known as a “quid pro quo” — has to be explicit for a campaign donation to be considered a bribe. With his pro-development record, Sittenfeld argues he would have voted in favor of the developers regardless of the donation.

Dozens of high-profile legal scholars, including President Donald Trump’s attorney general and President Barack Obama’s White House counsel, signed a brief to the court that argued Sittenfeld’s conduct was not criminal.

The authors said that the councilman’s “statements of puffery” “typify the everyday discourse between politicians and their supporters.” Sittenfeld's appeal is pending.

U.S. Attorney Todd W. Gee for the Southern District of Mississippi, addresses a reporter's question at a news conference, Wednesday, Nov. 8, 2023, in Jackson, Miss. Approximately 40 people with connections to multiple states and Mexico were arrested Tuesday, Jan 23, 2024, after a four-year federal investigation uncovered multiple drug trafficking operations throughout East Mississippi, federal prosecutors announced. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis, File)

U.S. Attorney Todd W. Gee for the Southern District of Mississippi, addresses a reporter's question at a news conference, Wednesday, Nov. 8, 2023, in Jackson, Miss. Approximately 40 people with connections to multiple states and Mexico were arrested Tuesday, Jan 23, 2024, after a four-year federal investigation uncovered multiple drug trafficking operations throughout East Mississippi, federal prosecutors announced. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis, File)

The prosecution of Owens, Lumumba and Banks is being handled by President Joe Biden appointee U.S. Attorney Todd Gee, a Vicksburg native who previously served as lead counsel for U.S. Congressman Bennie Thompson on the House Homeland Security Committee.

Thompson, the only Democrat in Mississippi’s delegation, recommended Gee for the position. Most recently, Gee was a deputy chief of the Public Integrity Section of the U.S. Department of Justice.

But the agents who conducted the sting came from out of state.

Sources close to the investigation said they believed two of the FBI agents posing as Nashville developers “Brian” and “Rob” were the same agents who went by “Brian” and “Rob” in similar investigations in Cincinnati and Columbus. The short, bald man playing the wealthy yacht-owning boss “Pauli” during Lumumba’s fundraiser, matches the description of the agent who went by “Vinny” in the Ohio cases.

Chris Lancaster, a realtor from outside of Nashville whose name was listed on the public development proposal in Jackson, shares a name with the businessman who worked undercover in a similar FBI sting in Tallahassee with an agent who also went by “Brian,” according to news reports. The logos used in those operations mirror the logo FST used.

These FBI agents’ assignments featured in criminal cases against at least the following public officials, according to news reports:

- Andrew “PG” Sittenfeld, Cincinnati City Council member

- Jeff Pastor, Cincinnati City Council member

- Larry Householder, Ohio Speaker of the House

- Andrew Gillum, Mayor of Tallahassee

- Scott Maddox, Tallahassee City Commissioner

- Paige Carter-Smith, executive director of the Tallahassee Downtown Improvement Authority

In Cincinnati and Columbus, the primary undercover agents went by aliases “Brian Bennett” and “Rob Miller.” Miller received a letter of censure from the FBI for his unprofessional conduct during the investigation. Like “Pauli” in the Jackson investigation, “Vinny” made a cameo appearance in the Cincinnati case, albeit a memorable one. At trial, Vinny described his persona as a “high-balling,” “wealthy investor boss,” the local TV station reported, who “liked to spend time on his yacht in Miami” and “was rich and rude.”

In Tallahassee, the newspaper characterized the agent known as “Brian Butler” as “bald-headed and stocky” and an agent known as “Mike Miller,” posing as an Atlanta-based developer, as “mysterious” and a “handsome bearded man” — descriptions matching the agents sources said dealt with the Jackson officials.

Lancaster, who had reportedly partnered with “Brian” in Tallahassee, appears to own a legitimate real estate firm in Hendersonville, Tennessee. The company boasts the down-to-earth sales style of Lancaster and his son: “muddy boots and dirty leather gloves in their pocket.”

Sources said two women, who they believe were also undercover agents, often accompanied the supposed developers. Those women joined Lee, the councilwoman, on her shopping spree at Maison Weiss women’s clothing store in Jackson’s Highland Village shopping center, sources said.

“Some of these four agents have checkered pasts and others have even engaged in misconduct in this particular investigation,” defense lawyers for Gillum, the former Tallahassee mayor, said in a court motion in his case, according to media reports. “Some have gotten plastered with alcohol during undercover meetings, some have actually offered and bought drugs, and some have even tried to ensnare their targets with women.”

The local FBI office did not respond to questions about these allegations.

By the time the out-of-state FBI agents came to Jackson, the city had been trying and failing to secure a developer to build a hotel complex on three empty blocks of Pascagoula Street for nearly two decades, especially since the $65 million convention center opened in 2009.

Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024.

Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024.

Under former Mayor Frank Melton in 2007, the city sold most of the land in question — a business deal that took years to unravel — to a Texas-based company pushing a proposal tied to a controversial developer previously charged and acquitted in a bribery scandal. Jackson Redevelopment Authority, which manages and oversees city property, eventually passed on that proposal in 2011.

At the end of former Mayor Harvey Johnson’s administration in 2013, he and then-Mayor-elect Chokwe Lumumba Sr. announced they’d reached a deal on a $60 million development in partnership with Hyatt Hotels. But it also fell through.

The next mayor, Tony Yarber, took at least $14,000 worth of campaign donations and other favors that prosecutors alleged Atlanta-based pastor and political consultant Mitzi Bickers gave him in an attempt to secure a piece of the convention center hotel project and a city wastewater contract in 2016. The FBI investigated this but eventually zeroed in on Bickers, who was convicted and sentenced to 14 years in prison for accepting $3 million in bribes to steer contracts in Atlanta when she served as the city’s director of human services.

In her 2022 trial, the prosecutor alleged Yarber received $80,000 worth of donations and gifts — described as bribes — from Bickers. Yarber testified to accepting a first class plane ticket, limousine rides and a private dance from a stripper during his trips to meet Bickers in Atlanta.

But Yarber also said he had no direct oversight of the awarding of Bickers’ contracts, which ultimately failed, and he was never charged. The $75 million hotel proposal Bickers helped put together, which Jackson Redevelopment Authority was still considering as the Bickers investigation became public, unsurprisingly died.

Asked about the current corruption probe in Jackson, Yarber said, “I’m just glad to be on the other side of the street watching this time.”

“But if there’s any difference, guess who didn’t get indicted?” Yarber told Mississippi Today Monday, denying that he ever testified to taking bribes from Bickers. “There was a lot of allegations. It was a lot of stuff, a lot of talk, a lot of writing. But yeah, no.”

Shortly after current Mayor Lumumba took office, the city spent at least a year developing a detailed downtown revitalization scope of work, which included a market analysis report, before issuing a Request for Proposals, or RFP, in 2019. An RFP is the document that spells out the city’s needs and officially solicits development proposals. Of the companies that responded to the bid, the city chose to interview one, but found their presentation insufficient and declined to pursue it, then-director of planning and development Mukesh Kumar told Mississippi Today.

Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (center) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis (right), listen as U. S. Marshals Service Director Ronald L. Davis (left) answers a question, during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023 in Jackson.

Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (center) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis (right), listen as U. S. Marshals Service Director Ronald L. Davis (left) answers a question, during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023 in Jackson.

The opportunity that those three empty blocks of Pascagoula street holds — or the missed opportunity it represents now — is bigger than downtown Jackson.

“Quality of life and being a revenue-generating economic driver for the city of Jackson is what that property has potential to be,” said Jhai Keeton, the current director planning and development. “It impacts everybody in central Mississippi. This is the heart of the state of Mississippi. Everybody says, ‘So goes Jackson, so goes the state.’ So goes that property.’”

The Tennessee realtor-turned-undercover-informant Lancaster and FBI agent Brian poked around Jackson for months before officially establishing FST in Miami in June of 2023.

The company was incorporated by a Jack Steele — which happens to be the pseudonym of an FBI informant who reportedly lived in Florida. It listed an operating address in Hendersonville, Tennessee, also where Lancaster’s company is located.

The next month in July, the city and Jackson Redevelopment Authority issued a new RFP for a convention center complex on the long-vacant downtown property.

Weeks later, while Lancaster was in town visiting a local lobbyist FST had hired, the informant asked where he could grab some cigars, and the lobbyist recommended the Downtown Cigar Company. The indictment said the informant had “a genuine interest in the products.”

The phony developer chummed it up at the lounge on Pearl Street — which the FBI would raid less than a year later — and shortly after met the owner, known to most as the county’s top prosecutor.

The indictment makes allusions, using Owens’ own quotes, to the DA running a larger money laundering operation out of the cigar bar: “I can do it in here. That’s why we have businesses. To clean the money. Right?” Owens said.

The indictment alleges Owens told the agents he was mixing the cash he received from them with “dope money and drug money and more than a million dollars” and storing it at the district attorney’s office. But the indictment does not include charges related to these comments.

Before Hinds County voters elected Owens as district attorney in 2019, the Terry native headed up the Mississippi office of the Southern Poverty Law Center, where he brought class action lawsuits on behalf of disenfranchised Mississippians and exposed unconstitutional child imprisonment. There, he was also accused of sexually harassing several women colleagues.

He opened Downtown Cigar Company in 2018. He also claims to be the co-founder and co-owner Magnolia 360 LLC, a real estate and property management firm run by the owner of a California-based tree service company.

Republican State Auditor Shad White, right, and Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens discuss the auditor's office investigation of the former director of Mississippi's welfare agency and four other people, accused of embezzling millions in federal money meant for the poor, Thursday, Feb. 6, 2020, in Jackson, Miss. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Republican State Auditor Shad White, right, and Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens discuss the auditor's office investigation of the former director of Mississippi's welfare agency and four other people, accused of embezzling millions in federal money meant for the poor, Thursday, Feb. 6, 2020, in Jackson, Miss. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

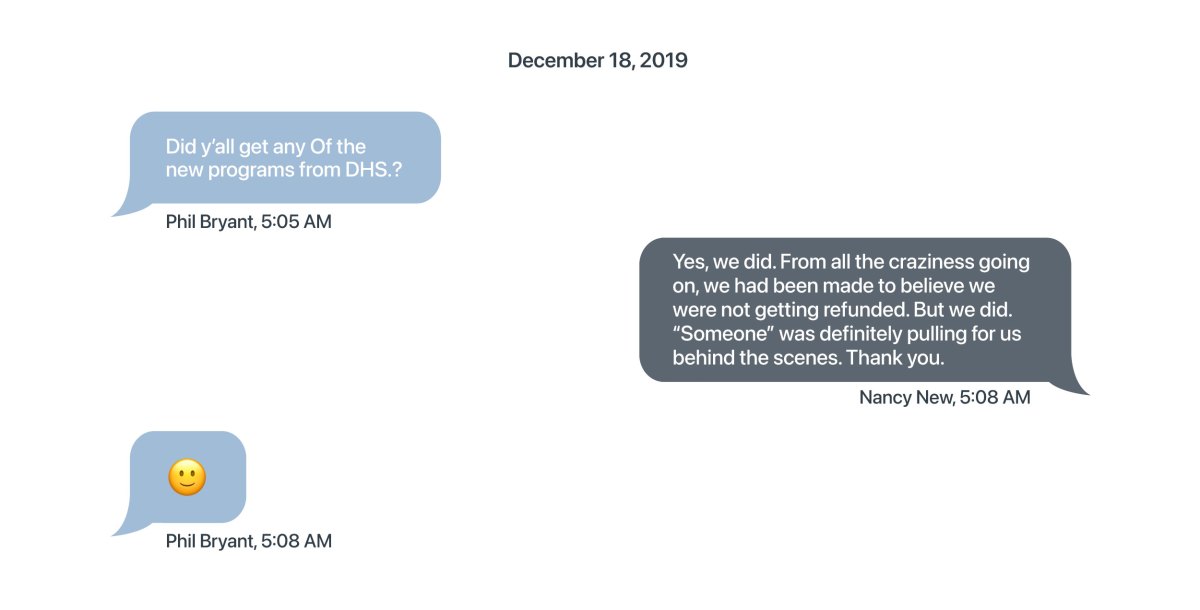

In early 2020, State Auditor Shad White, who went to the same church as Owens while they both converted to Catholicism, brought the local DA the findings of an eight-month investigation that would rock the state for years to come. State welfare officials and a politically-connected nonprofit had been illegally funneling millions of federal assistance for the poor to their family, friends and professional athletes.

Owens swiftly indicted six individuals before the U.S. Attorney's Office or FBI were even looped into the investigation — to the dismay of the federal government. Owens hasn’t charged any additional people in the case since.

Early on, the agents' conversations about development in downtown Jackson were frenetic. Keeton, the city planning director, said they talked about “buying Farish Street.”

“They were saying all the fuzzy, feel good stuff,” Keeton said.

He said he got turned off after they invited him to a strip club and after they once asked to push a meeting later in the day because they were “still hungover from last night,” Keeton recalled.

In the fall of 2023, FST didn’t participate in the city’s then-open bid for downtown development proposals. By the deadline for submissions, the city had received none.

Regardless of the opportunity the agents would later pretend to pursue, they wanted Owens on their team. In November of 2023, Owens won reelection. The agents came to Jackson to celebrate with him, secretly recording him into the night.

“This is the part time job,” Owens said, describing his role as district attorney, “to get leverage for the full time job. This is the part time job to get the conversations and the access.”

All while the U.S. Attorney's Office was operating a sting on Owens the businessman at night, during the day, it was coordinating with Owens the prosecutor on grand jury matters.

The day after the election, Owens and Smith negotiated payment of $100,000 each for their roles in consulting the developers, the indictment alleges. A third person, identified as a witness, negotiated payment of $50,000.

The next month, Owens sent the agents the city’s previous RFP and took the first of two trips to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, north of Miami, to meet with the men. During a meeting on their yacht, the agents handed the district attorney $125,000 in cash — the fees for Owens and his associates. Owens said that cash was “easier,” according to the indictment, “and that he had brought a bag on the trip specifically for that purpose.”

The District Attorney’s Office’s policies and procedures do not prohibit the prosecutor from having outside business interests. In his latest Statement of Economic Interest he’s required to file with the Mississippi Ethics Commission, Owens listed himself as a partner for Facility Solutions Team.

“If the money is for an innocent purpose on the face of it, they (the FBI) are basically financing the target to keep them involved and that shows a lack of judgment at least,” longtime San Francisco trial lawyer James Brosnahan told Mississippi Today.

Brosnahan, who has practiced for over six decades, including five years as a federal prosecutor, argued that’s what undercover agents did to his client, former school board member and political consultant Keith Jackson. Undercover FBI agents had hired Jackson and paid him “to do perfectly lawful things,” Brosnahan told reporters after Jackson pleaded guilty in 2014 to bribing former California state Sen. Leland Yee with campaign contributions.

“They also promised him great wealth. After they had done that, they began to embroil him in the matter that brings him to his plea,” Brosnahan said. “What authorized them to come into the Bay Area and do what they did? Is this government doing what we want them to do? My answer is no.”

An FBI agent in that case posing as a businessman from Atlanta, whose evidence was used to justify wiretapping the target, was shortly after removed from Keith Jackson’s case for financial misconduct, according to media reports.

Brosnahan also found that in the course of its Bay Area investigation, the FBI sent agents disguised as real estate investors to Joe Montana to lure him into the corruption sting. “It shows the deepest lack of judgment I can imagine,” Brosnahan said at the time. But the former 49ers quarterback didn’t bite, according to media reports.

Angelique Lee speaks at a Mississippi Poor People's Campaign rally at the state Capitol in Jackson, Miss., Monday, June 18, 2018, calling out for lawmakers and statewide elected officials to address education more fully. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Angelique Lee speaks at a Mississippi Poor People's Campaign rally at the state Capitol in Jackson, Miss., Monday, June 18, 2018, calling out for lawmakers and statewide elected officials to address education more fully. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

In January, Owens began setting up meetings with each of the city council members so his new supposed business partners could gauge their interest in working with them.

“There was very little discussion of what they were offering,” council member Vernon Hartley said.

Hartley said the men wanted to pay for his salmon croquette at Walker’s Drive-In, but he insisted on paying his own bill. While some of the council found the phony developers unimpressive, Lee, and allegedly Banks, took the bait.

During their first meeting with Banks, one of the FBI agents asked what the council member would need to support the development moving forward.

“Fifty grand as soon as possible would help,” Banks said, according to the indictment.

The next night, Banks was pulled over for drinking and driving, but he wasn’t booked; the state trooper released him to Owens, WLBT reported. A judge would later require Banks to install a breathalyzer in his car’s ignition.

Banks wasn’t the only one dealing with personal issues. Lee, who was also charged with a DUI the previous year, was in thousands of dollars in debt from her 2020 election campaign. The sign printing shop she allegedly stiffed had sued her, and the court began garnishing her city council wages in 2023, WLBT reported.

The annual pay for Jackson City Council members, a part time job, is around just $25,000.

In the following weeks and months, agents spent thousands wining and dining the politicians at expensive restaurants around Jackson.

In the back room at the cigar lounge one night, Owens handed Banks an envelope containing $10,000, the indictment alleges, and asked the council man if he was comfortable taking cash because it was “not a check like we normally do.”

To make sure Banks was on board, prosecutors allege, FST also funded a paid internship position at the district attorney’s office for Banks’ family member and a driver service for Banks as he dealt with the aftermath of his DUI arrest — benefits totaling $6,300.

Two days later, Owens allegedly made the $10,000 payment towards Lee’s campaign debt in exchange for her future vote.

While this was going on, the city and Jackson Redevelopment Authority opened a new downtown project bid on Jan. 31. This time, the bid was a Request for Statements of Qualifications, which solicits information from prospective developers but does not require as many details about specific construction plans. The city said it was seeking a 335-room hotel, open entertainment space and parking garage.

By the end of February, the request was set to expire in two weeks and Keeton, the planning director, said the city hadn’t seen any nibbles — besides from FST. Keeton said he asked the mayor to extend the deadline to April 30 to give developers more time to respond.

“When it was extended, someone said to me that the (FST) developer was like, ‘Well, if it’s about money, we’ll wire $90 million tomorrow,’ and I said, ‘For what?’ That’s stupid,” Keeton said. “When you talk money around people that don’t have money, they get excited about it.”

FST pretended to partner with a Michigan-based construction and property management company called Contour Development to form the joint venture Jackson Development Group, according to the team’s 32-page statement dated March 10.

The document names Owens and his cousin Smith as the development group’s local partners. In describing Owens’ qualifications, it says his company Magnolia 360 manages more than 100 affordable homes and three apartment complexes in Jackson and that Owens has “spent the last decade recruiting business and developments in downtown Jackson.”

On the same day FST finalized the proposal, Owens wrote City Hall using his district attorney’s office email to confirm the investor group would be hosting a fundraiser for the mayor in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Owens indicated he was writing “Per Mayor Lumumba’s request.”

On March 19, Owens filed paperwork to incorporate FST in Mississippi, listing the cigar lounge as the address and his personal email as the contact, and he also opened a Mississippi bank account for the company.

Owens emailed Lumumba’s executive assistant Tiffany Murray an itinerary for the Florida trip, which included a “sunset cruise.” He attached an official letter, dated a month earlier on Feb. 10 and signed by Lancaster, inviting the mayor to the fundraiser to discuss their proposal for a state-of-the-art mixed-use development in downtown Jackson.

“We have a private charter that me and my detail will accompany the Mayor on,” Owens wrote.

Mississippi Today retrieved the emails through a public records request.

Days before the trip, prosecutors allege the agents met with Owens and Banks and told the officials they wanted the bid response deadline moved back and Banks responded, “If that’s an advantage for you guys, yes.”

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba speaks during a news conference at City Hall in Jackson, Miss., regarding updates on the ongoing water infrastructure issues, Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2022. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba speaks during a news conference at City Hall in Jackson, Miss., regarding updates on the ongoing water infrastructure issues, Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2022. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

At a mansion on a street lined with palm trees in Fort Lauderdale, sources said the mayor delivered impassioned remarks about Jackson’s challenges and its potential.

Lumumba, an attorney, first ran for mayor when he was just 30 years old in 2014 shortly after his father, former Mayor Chokwe Lumumba Sr., died eight months into office. After Lumumba’s loss in that election, he ran again in 2017 and earned a stunning 55% of the vote in a field of nine candidates in the Democratic primary. After his election, he promised to make Jackson “the most radical city on the planet.”

On the yacht with the FBI agents, Owens explained to Lumumba how he was dividing up the money — which the government alleged was meant to conceal the bribe. “We filtered it through several accounts in a way we comfortable doing,” Owens said, according to the indictment.

Owens assured Lumumba that the team was delivering $50,000 then, but that it planned to deliver more down the road, “to make sure there’s no worries about you financially in this thing cause you’re as big part of this thing as anybody,” according to the indictment.

The informant then asked Lumumba to move the Statement of Qualifications deadline, the indictment alleges. The mayor called Keeton, his planning director overseeing the bid process.

Keeton is described the phone call: “Phone rings. ‘What’s up boss man?’ ‘Aye man, let’s go ahead and move that date back.’ ‘Alright cool.’ ‘Alright goodbye.’ That was the conversation.”

The request didn’t come as a surprise, Keeton said, because the bid had already been open longer than planned and the mayor didn’t “want to lose anyone we’ve got hoping to get new people.”

The indictment alleges that Lumumba understood the campaign donation from the developers was in exchange for him directing his employee to change the deadline, but it does not include quotes from Lumumba about this.

Unlike Owens, the indictment does not heavily quote Lumumba. The mayor is quoted saying “yeah” three times and “okay” once in reference to the structure of the campaign contributions, but the indictment does not quote him in reference to the date change.

Later that night, the indictment alleges, the agents showered cash on Lumumba at the strip club.

While Lee and Banks allegedly took cash and other personal favors, the only bribe Lumumba has been charged with taking are the campaign contributions. Lumumba declined to provide Mississippi Today a record of his most recent campaign contributions, which he is not required to report until January.

Mississippi campaign finance law is notoriously loose, and there are almost never consequences for non-reporting. The state has no limit on the dollar amount an individual, LLC or PAC can donate to candidates, and there is no prohibition on donations from those doing business with the government or “gift law” curbing lavishment from lobbyists.

In theory, laws requiring candidates to disclose their campaign contributors should provide the transparency needed to examine whether wealthy contractors are buying politicians. But the statutes are confusing, and where the law is clear, there is little enforcement, especially on the municipal level.

Though Lumumba is statutorily required to file campaign finance reports with the city clerk annually in non-election years, Lumumba has not filed a report since his 2021 reelection.

“Unfortunately, that is not uncustomary for my campaign,” he said at a press conference in October, the Clarion Ledger reported.

Municipal Clerk Angela Harris would not answer questions about her office’s handling of nonfilers. The Secretary of State, which receives reports from state candidates, is required to turn over possible reporting violations to the Mississippi Ethics Commission. But the ethics commission director Tom Hood said to his recollection, his office had never received notice of a possible violation from a city clerk, and there’s no mention of city candidates in the law that authorizes the commission to assess fines.

Meanwhile, pay-to-play in state government is so common, State Auditor White casually described the occurrence in a Facebook post advertising a recent study his office commissioned: “A lot of waste … works like this: a lobbyist walks in the door and convinces an agency head they need to buy a new thing. The lobbyist and the agency head go to a lawmaker and ask them to appropriate some money for the new thing (and the lobbyist gives the lawmaker a campaign donation, just for good measure). The money gets appropriated, the agency head buys the thing, and everyone is happy – except the taxpayer, who had no idea this was happening.”

According to a 2023 Mississippi Today investigation, Gov. Tate Reeves has received $1.6 million in campaign donations from companies that have received more than $1.4 billion in state contracts or grants since 2003.

Sittenfeld’s lawyer stressed to jurors that the councilman had taken 1,800 donations during his campaign, but the only ones causing him trouble were those from the FBI agents. “If any of the other donations were illegal, you would have heard of them,” the lawyer said in closing arguments, according to news reports.

Both Lumumba and Owens made no indication of plans to step down from office. The trial likely won’t occur for months or longer. Each of them strongly defended themselves against the charges.

During one of the meetings with the agents, in which Owens described how he “want(ed) the paper trail to look” for the campaign contributions, the state’s most populous county’s top prosecutor made his goal known: “At the end of the fucking day, my most important job is to keep everybody out of jail or prison because I’m not fucking going.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

![]()

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens (right) addresses a question as Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (left) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023, in Jackson.

Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens (right) addresses a question as Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (left) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023, in Jackson. Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024.

Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024. A photo included in the federal indictment shows Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, left, talking on the phone while sitting with Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens on the yacht.

A photo included in the federal indictment shows Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba, left, talking on the phone while sitting with Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens on the yacht. The FBI found $20,000 in cash hidden in a lockbox disguised as a book titled, “The Constitution of The United States of America,” according to the indictment.

The FBI found $20,000 in cash hidden in a lockbox disguised as a book titled, “The Constitution of The United States of America,” according to the indictment. U.S. Attorney Todd W. Gee for the Southern District of Mississippi, addresses a reporter's question at a news conference, Wednesday, Nov. 8, 2023, in Jackson, Miss. Approximately 40 people with connections to multiple states and

U.S. Attorney Todd W. Gee for the Southern District of Mississippi, addresses a reporter's question at a news conference, Wednesday, Nov. 8, 2023, in Jackson, Miss. Approximately 40 people with connections to multiple states and  Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024.

Lots used for parking in front of the Jackson Convention Complex Center, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024. Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (center) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis (right), listen as U. S. Marshals Service Director Ronald L. Davis (left) answers a question, during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023 in Jackson.

Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba (center) and Jackson Police Chief James Davis (right), listen as U. S. Marshals Service Director Ronald L. Davis (left) answers a question, during a Violent Crime Prevention Summit held at the Two Mississippi Museums, Thursday, Jan. 5, 2023 in Jackson. Republican State Auditor Shad White, right, and Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens discuss the auditor's office investigation of the former director of Mississippi's welfare agency and four other people, accused of embezzling millions in federal money meant for the poor, Thursday, Feb. 6, 2020, in Jackson, Miss. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Republican State Auditor Shad White, right, and Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens discuss the auditor's office investigation of the former director of Mississippi's welfare agency and four other people, accused of embezzling millions in federal money meant for the poor, Thursday, Feb. 6, 2020, in Jackson, Miss. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis) Angelique Lee speaks at a Mississippi Poor People's Campaign rally at the state Capitol in Jackson, Miss., Monday, June 18, 2018, calling out for lawmakers and statewide elected officials to address education more fully. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Angelique Lee speaks at a Mississippi Poor People's Campaign rally at the state Capitol in Jackson, Miss., Monday, June 18, 2018, calling out for lawmakers and statewide elected officials to address education more fully. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis) Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba speaks during a news conference at City Hall in Jackson, Miss., regarding updates on the ongoing water infrastructure issues, Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2022. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba speaks during a news conference at City Hall in Jackson, Miss., regarding updates on the ongoing water infrastructure issues, Tuesday, Sept. 6, 2022. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)