America’s biggest education experiment is happening in Houston

This article first appeared on Houston Landing and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Todo cambió. Everything changed.

That’s how Arturo Monsiváis described life this year for his fifth-grade son, who attends Houston ISD’s Raul Martinez Elementary School. Teachers raced through rapid-fire lessons. Students plugged away at daily quizzes. Administrators banned children from chatting in the hallways.

Sitting in the parent pickup line on the last day of school, Monsiváis said his son often complained that the new assignments were too difficult. But Monsiváis, a construction worker, wouldn’t accept any excuses: Study hard, he advised.

“I tell my son, ‘Look, do you want to be working out here in the sun like me, or do you want to be in an office one day? Think about it,’” Monsiváis said.

The seismic changes seen by Monsiváis’ son and the 180,000-plus students throughout HISD this school year are the result of the most dramatic state takeover of a school district in American history, a grand experiment that could reshape public education across Texas and the nation.

In stunningly swift fashion, HISD’s state-appointed superintendent and school board have redesigned teaching and learning across the district, sought to tie teacher pay more closely to student test scores, boosted some teacher salaries by tens of thousands of dollars and slashed spending on many non-classroom expenses.

(Left photo) Demonstrators rally in front of Hattie Mae White Educational Support Center in opposition to a possible takeover of the HISD's elected board by the TEA. (Houston Landing file photo / Marie D. De Jesús) (Right photo) From left, Jaelauryn Brown, 8, Jaedis Brown, 13, and Jaeson Brown, 4, walk through the front rotunda of Houston ISD's Wheatley High School on June 1, 2023, in Houston's Greater Fifth Ward. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

(Left photo) Demonstrators rally in front of Hattie Mae White Educational Support Center in opposition to a possible takeover of the HISD's elected board by the TEA. (Houston Landing file photo / Marie D. De Jesús) (Right photo) From left, Jaelauryn Brown, 8, Jaedis Brown, 13, and Jaeson Brown, 4, walk through the front rotunda of Houston ISD's Wheatley High School on June 1, 2023, in Houston's Greater Fifth Ward. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

The changes in HISD rival some of the most significant shake-ups to a public school system ever, yet they’ve received minimal national media attention to date.

Still, district leaders, citing private conversations with researchers and superintendents, said education leaders throughout the U.S. are following the HISD efforts to see whether they may be worth replicating. Adding to the intrigue: Texas lawmakers have looked in recent years to policies used by HISD’s new superintendent, former Dallas Independent School District chief Mike Miles, as inspiration for statewide legislation.

“I think people are watching and waiting,” HISD Board Secretary Angela Lemond Flowers said. “We’re stepping out there big, and it’s important because we are a big district and we have lots of students that we need to make sure we’re serving better. Not in the next generation. Not in five years. Like, immediately.”

Houston ISD Superintendent Mike Miles. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

Houston ISD Superintendent Mike Miles. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

Miles, the chief architect of HISD’s new blueprint, has pointed to early successes — including strong improvement in state test scores this year — as evidence that his model works where others have failed. For decades, Black and Latino children in urban school districts like Houston have trailed well behind wealthier and white students in school.

Miles’ critics, however, have blasted his approach as an unproven, unwanted siege on the district orchestrated by Texas Republicans. They cite high teacher turnover headed into the next school year and long-term questions about the affordability of Miles’ plans as indicators the effort may be doomed.

Regardless of whether the HISD intervention becomes a shining success, a historic failure or something in between, it could help answer one of the most pressing questions in education: Can a large, urban public school district dramatically raise student achievement and shrink decades-old performance gaps, ultimately helping to close America’s class divide?

'Back to the future'

The HISD intervention represents “by far the most bizarre state takeover that we’ve ever seen,” said Jonathan Collins, a Columbia University Teachers College associate professor who has worked with another takeover district, Providence Public Schools.

Typically, states take the reins of districts following major academic or financial scandals. HISD, by comparison, has scored at a “B” level in recent years under Texas’ A-through-F rating system and kept its financial house in order.

But in 2019, HISD allowed one campus, Wheatley High School in Greater Fifth Ward, to receive a seventh straight failing grade from the state. Wheatley’s scores triggered a Texas law — authored in 2015 by a Houston-area Democrat fed up with years of poor outcomes at some HISD schools — that gave Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath the right to replace the district’s school board.

Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath. (Houston Landing file photo / Sergio Flores)

Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath. (Houston Landing file photo / Sergio Flores)

After three years of legal battles with HISD trustees, who tried to halt the takeover, Morath emerged victorious. He appointed Miles and nine local residents to run the district in June 2023.

Rather than focusing on the handful of HISD schools with the most flagrant academic underperformance, Miles overhauled a huge swath of the district — 85 out of roughly 270 schools — in his first year.

In doing so, Miles relied heavily on practices pioneered in the 2000s and 2010s by the so-called “education reform” movement, a loose collection of politicians, charter school organizers and district chiefs.

The group argued that instilling a “no-excuses” attitude toward student achievement and partially tying teacher pay to test score growth could dramatically improve American education. Miles implemented a similar playbook during his three-year stint leading Dallas ISD, an approach that helped improve student test scores but contributed to a near-doubling of the district’s teacher turnover rate.

In recent years, the reform movement that inspired Miles’ policies has largely fallen out of favor. The changes haven’t consistently moved the needle on exam results nationwide, while high-stakes testing has become less popular.

What hisd families say

The Houston Landing spoke to about 30 family members of children attending campuses overhauled this year, asking for their thoughts on the changes. Some of their thoughts are featured throughout this story.

Mary Daughtery, grandmother, Hilliard Elementary School

Daughtery’s four grandchildren at Hilliard Elementary spent the year complaining: Classes were harder, school culture was more militant and, at the end of the year, school leaders skipped the campus’ typical end-of-year celebrations to squeeze in more instruction.

“They used to have a graduation march and awards … but they’re not doing it this year,” Daughtery said. “It’s like, pick up and leave.”

One grandchild, Lauren Daughtery, who just finished fourth grade, said she hadn’t made up her mind on the demanding classes — the assignments were tougher not in a good or bad way, but in a “medium way.” Lauren had learned “a little bit” more than usual this year, she said, but her teacher was “too mean,” sometimes raising her voice.

But to Miles, the movement fell short for one main reason: It didn’t go big enough.

So Miles required over 1,000 HISD teachers at over two dozen campuses to reapply for their jobs, ultimately replacing about half of them. He rearranged how educators teach students, requiring them to use an approach that mandates students must participate in class roughly every four minutes. And he rolled out new lesson plans for about a third of the district’s schools that included short, daily quizzes in nearly all subjects.

Thomas Toch, the director of Georgetown University’s FutureEd think tank, said Miles’ approach “feels like sort of a ‘back to the future’ moment.” The HISD overhaul currently represents “the largest effort to implement school improvement at scale,” Toch said.

While major public school reforms aren’t new, the scope and speed of HISD’s overhaul stand out.

Former District of Columbia Public Schools chancellor Michelle Rhee famously fought in the late 2000s to partially tie pay to exam score growth, but she didn’t dictate classroom instruction techniques and school staffing models. New Orleans turned its 45,000-student district into an all-charter school system post-Hurricane Katrina, but fewer children saw big changes than in HISD. Even Miles’ most ambitious reforms in Dallas targeted a fraction of the students as HISD.

“This is an effort, the largest in the country, to turn around a traditional, urban district,” Miles said. “That’s what we’re engaged in.”

A student works at a team center, Aug. 31, 2023, at Houston ISD's Sugar Grove Academy in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

A student works at a team center, Aug. 31, 2023, at Houston ISD's Sugar Grove Academy in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

David Espinoza, at right, looks over his students’ work during an Art of Thinking class Jan. 25 at Houston Math, Science, and Technology Center High School in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

David Espinoza, at right, looks over his students’ work during an Art of Thinking class Jan. 25 at Houston Math, Science, and Technology Center High School in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

A teacher helps a student in one of the team centers Aug. 31, 2023 at Sugar Grove Academy in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

A teacher helps a student in one of the team centers Aug. 31, 2023 at Sugar Grove Academy in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

Wider model?

One year in, Miles’ administration has scored some key victories.

The elementary and middle schools Miles targeted for changes saw, on average, a 7 percentage point increase in the share of students scoring at or above grade level on statewide reading and math tests, commonly known as the STAAR exams. Other HISD schools saw a 1 percentage point increase, while state averages slid in math and remained flat in reading.

“I think you can say pretty clearly that (the transformation model) has been working well,” Miles said when the scores came out.

HISD also has made some progress in meeting legal requirements for serving students with disabilities, an area in which the district has struggled for more than a decade, according to state-appointed conservators monitoring the district.

But other indicators could spell trouble for Miles’ administration in year two and beyond.

As of early June, four weeks before educators’ deadline to resign without penalty, roughly one-quarter of HISD’s 11,000-plus teachers had left their positions ahead of the upcoming school year, district administrators said. Historically, HISD’s teacher turnover rate has hovered around 15 to 20 percent.

The departures follow widespread complaints that, under Miles’ leadership, district administrators micromanage teachers by frequently observing classroom instruction and providing feedback. David Berry, a former journalism teacher at Wisdom High School, recalled a fall meeting where district administrators scolded teachers for using student engagement strategies too infrequently.

“They proceeded to rip us apart,” said Berry, who plans to teach in a neighboring district next year. “I’ve never been talked to like that as a teacher, really, as a grown up.”

The financial viability of Miles’ plans also remains in question. HISD ran a nearly $200 million deficit on a roughly $2.2 billion budget in Miles’ first year, with much of the shortfall tied to dramatic increases in staffing and pay at overhauled schools. The district is budgeting a similar deficit next year, though it plans to use $80 million in unspecified property sales to lessen the blow.

what hisd families say

Maria Colunga, mother, Raul Martinez Elementary School

Colunga’s fourth grade son had always earned As and Bs, but under new lesson plans with daily quizzes and extra work packets, his grades slid to Cs and Ds. The trend spooked Colunga, and she mulled alternatives, such as transferring her son to a different school next year. But the child’s teacher assured the family that he would adjust and get back on track.

“Sure enough, by the second progress report he started bringing up his grades,” Colunga said. “But I would ask him and he would say, ‘It’s hard, it’s fast, the pace is really fast for me.’”

Colunga added: “I’m like, ‘As long as it works and you stay at your grade level that I’m used to seeing you in,’ then I’m happy.’”

Still, if HISD can continue to post strong test scores, history suggests Miles’ model could soon spread beyond Houston.

Texas lawmakers, inspired by Miles’ work, passed legislation in 2019 that allocated money to school districts that adopted teacher evaluation systems like the one he used in Dallas. Texas districts received nearly $140 million in 2022-23 under the law.

They also passed a law that allowed long-struggling campuses to skirt closure by replicating a turnaround plan Miles implemented in Dallas. Participating schools have to provide high levels of feedback on instruction, extend school hours and offer incentives for top-rated teachers and principals.

Miles last fall said his Houston work is “not a test case” for statewide policy. More recently, however, he alluded to the possibility of his model being implemented more widely.

“There's a lot of interest across the country, mostly from people who are educators, of what's happening here,” Miles said in a May interview. “This actually could be a proof point for others if it can be done."

Harvard Graduate School of Education economist Thomas Kane, who has researched students struggling to rebound from the pandemic nationwide, said he believes HISD’s overhaul could interest many district leaders.

“If there have been substantial improvements in student achievement gains simultaneously with improvements in student attendance, I think that will grab a lot of attention nationally and will make people curious about the Houston reforms," Kane said.

Kourtney Revels, at center, the mother of a third-grade student at Houston ISD's Elmore Elementary School, confronts district staff limiting public access to a June 2023 school board meeting at HISD headquarters in northwest Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Annie Mulligan)

Kourtney Revels, at center, the mother of a third-grade student at Houston ISD's Elmore Elementary School, confronts district staff limiting public access to a June 2023 school board meeting at HISD headquarters in northwest Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Annie Mulligan)

Houston ISD teacher Jonathan Bryant holds a sign showing his disapproval of the district's newly appointed board during a June 2023 public meeting at the HISD headquarters in northwest Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Annie Mulligan)

Houston ISD teacher Jonathan Bryant holds a sign showing his disapproval of the district's newly appointed board during a June 2023 public meeting at the HISD headquarters in northwest Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Annie Mulligan)

Standing on a chair, Rosalie Longoria spoke to the Houston ISD board members during an August 2023 school board meeting in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Marie D. De Jesús)

Standing on a chair, Rosalie Longoria spoke to the Houston ISD board members during an August 2023 school board meeting in Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Marie D. De Jesús)

Community members attending Houston ISD's school board meeting stand and hold ‘thumbs down” signage in opposition to Superintendent Mike Miles' plans announced in June 2023 at the district's headquarters in northwest Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Douglas Sweet Jr.)

Community members attending Houston ISD's school board meeting stand and hold ‘thumbs down” signage in opposition to Superintendent Mike Miles' plans announced in June 2023 at the district's headquarters in northwest Houston. (Houston Landing file photo / Douglas Sweet Jr.)

Community appetite

Even if HISD produces remarkable gains in the coming years, many elected school boards — which answer directly to local voters, unlike Miles and the state-appointed board — might not stomach upheaval on the level of Houston.

Miles’ policies, coupled with his bulldozer style of leadership, have prompted family protests and student walkouts throughout his first year. Typically, more than 100 community members criticize his administration during school board meetings. In one particularly heated exchange from June, a district administrator repeatedly yelled “scoreboard” at a group of jeering audience members while pointing to a screen displaying student test scores.

Even some families that approached Miles’ arrival with hopefulness have turned against the district’s leadership. Tish Ochoa, the mother of an HISD middle schooler, said she began the school year “cautiously optimistic” but soured on Miles’ plans as she heard reports of stressed-out teachers and changes to high-performing schools.

“I wouldn’t say that I was like, ‘Rah-rah takeover,’ but I was also like, ‘I hope this works.’ I was supportive of the new administration coming in,” Ochoa said. “I don’t feel that way anymore.”

Houston ISD Superintendent Mike Miles observes a classroom on Aug. 11, 2023, at Sugar Grove Academy in Houston's Sharpstown neighborhood. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

Houston ISD Superintendent Mike Miles observes a classroom on Aug. 11, 2023, at Sugar Grove Academy in Houston's Sharpstown neighborhood. (Houston Landing file photo / Antranik Tavitian)

Miles has argued that many families quietly back his administration. However, few community members have spoken out in support of his efforts, save for a handful of nonprofits and civic groups largely backed by big-dollar philanthropy or business organizations.

At HISD’s overhauled schools, many parents said they’re open to timers ticking in classroom corners and rapid-fire quizzes — so long as their children aren’t left behind.

“I don’t care about the changes,” McReynolds Middle School mother Christina Balderas said. “The only thing I care about is when my daughter gets home and she tells me, ‘This is what I learned today, mom.’ They can have all the changes in the world that they need.”

what hisd families say

Sheena Washington, mother, Bruce Elementary School

Washington’s son typically looked forward to summer after finishing at the top of his class. But after completing fourth grade this year, he had to attend summer school because his grades slipped in math — a penalty Washington found out about last-minute in a call from the school, she said.

When Washington asked her son about his grades, he said he struggled to finish his classwork on time.

“I was like, ‘But it’s their fault because they timed everything,’” Washington said. “It was chaotic this year as far as the kids getting to learn the new system with the new superintendent.”

In the next few years, Morath likely will begin gradually bringing some of HISD’s elected trustees back onto the school board, as outlined in state law. From there, they will decide which Miles policies to keep or dismantle.

Three of HISD’s nine elected trustees responded to interview requests for this story: Sue Deigaard, Plácido Gómez and Dani Hernandez. They said they want to see multiple years of data on the impact of Miles’ approach before solidifying their impressions.

Most said they would reverse unpopular details of Miles’ plan, such as requiring some children to carry a traffic cone to the bathroom as a hall pass, but they found early evidence of the academic impact promising.

“If I had to make a decision right now of whether to continue (the overhaul model), I would,” said Gómez, who represents parts of eastern and central HISD. “There isn’t enough data to say, ‘This definitely works,’ but there’s enough for me to want to continue on this path.”

Asher Lehrer-Small covers Houston ISD for the Landing and Danya Pérez covers diverse communities. Reach them at asher@houstonlanding.org and danya@houstonlanding.org.

Danielle Stephen, 20, found herself homeless during her teenage years. Stephen now serves in organizations supporting homeless youth and is working to get her psychology degree from Houston Christian University. (Marie D. De Jesús / Houston Landing)

Danielle Stephen, 20, found herself homeless during her teenage years. Stephen now serves in organizations supporting homeless youth and is working to get her psychology degree from Houston Christian University. (Marie D. De Jesús / Houston Landing)

(Top left) Danielle Stephen, 20, has a beverage she received May 8 at Montrose Street Reach. Montrose Street Reach is an organization dedicated to transitioning at-risk people off the streets. (Top right) Stephen holds a few dollars before offering the cash to Montrose Street Reach. (Bottom left) Stephen attends a Montrose Street Reach service, which she calls "street church." (Bottom right) Stephen closes her eyes while Mike MacLaughlin prays for her at a Montrose Street Reach service. (Marie D. De Jesús / Houston Landing)

(Top left) Danielle Stephen, 20, has a beverage she received May 8 at Montrose Street Reach. Montrose Street Reach is an organization dedicated to transitioning at-risk people off the streets. (Top right) Stephen holds a few dollars before offering the cash to Montrose Street Reach. (Bottom left) Stephen attends a Montrose Street Reach service, which she calls "street church." (Bottom right) Stephen closes her eyes while Mike MacLaughlin prays for her at a Montrose Street Reach service. (Marie D. De Jesús / Houston Landing) Prince Hayward, a traditional support specialist at University of Houston’s Charge Up program, at center, says hello to a friend while grabbing lunch with “Spider,” at left, a young adult he is mentoring, on April 26 at Chipotle Mexican Grill in Houston. (Antranik Tavitian / Houston Landing)

Prince Hayward, a traditional support specialist at University of Houston’s Charge Up program, at center, says hello to a friend while grabbing lunch with “Spider,” at left, a young adult he is mentoring, on April 26 at Chipotle Mexican Grill in Houston. (Antranik Tavitian / Houston Landing) Prince Hayward, a traditional support specialist at the University of Houston’s Charge Up program, takes a meeting while getting a haircut by Walter White III on April 18 in Houston. (Antranik Tavitian / Houston Landing)

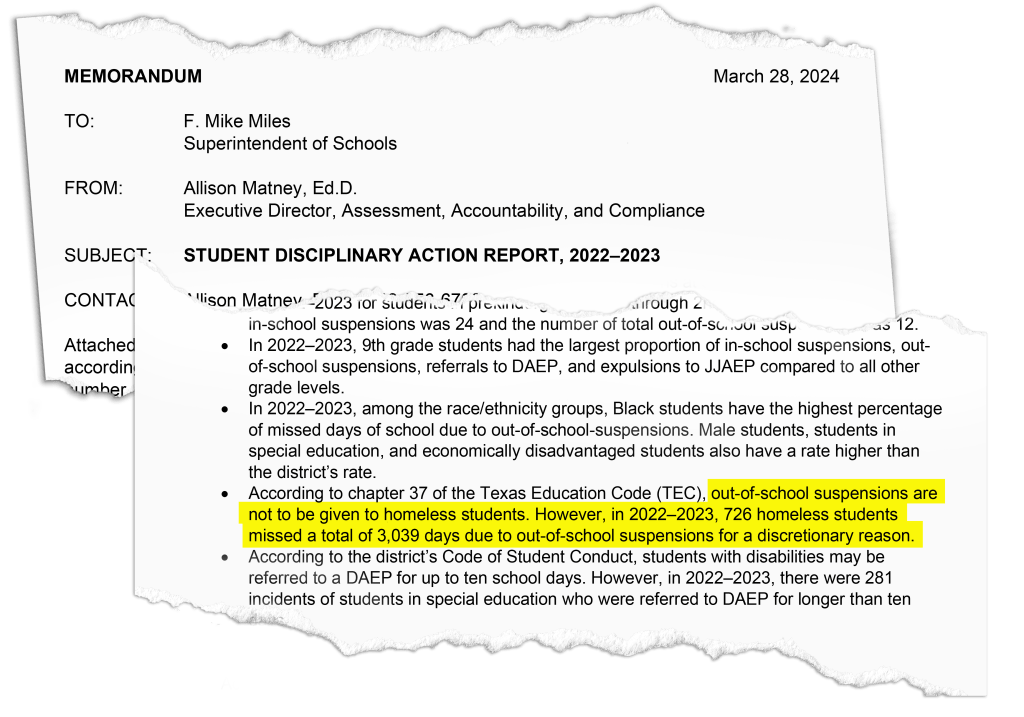

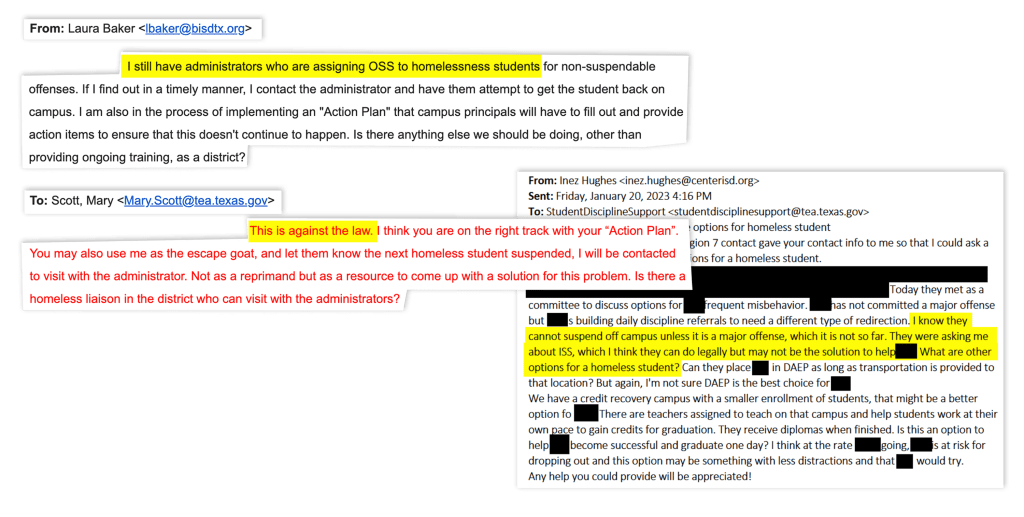

Prince Hayward, a traditional support specialist at the University of Houston’s Charge Up program, takes a meeting while getting a haircut by Walter White III on April 18 in Houston. (Antranik Tavitian / Houston Landing) A Houston ISD report from 2024 detailed the district's continued practice of suspending homeless students for discretionary reasons, which are illegal under Texas law.

A Houston ISD report from 2024 detailed the district's continued practice of suspending homeless students for discretionary reasons, which are illegal under Texas law.

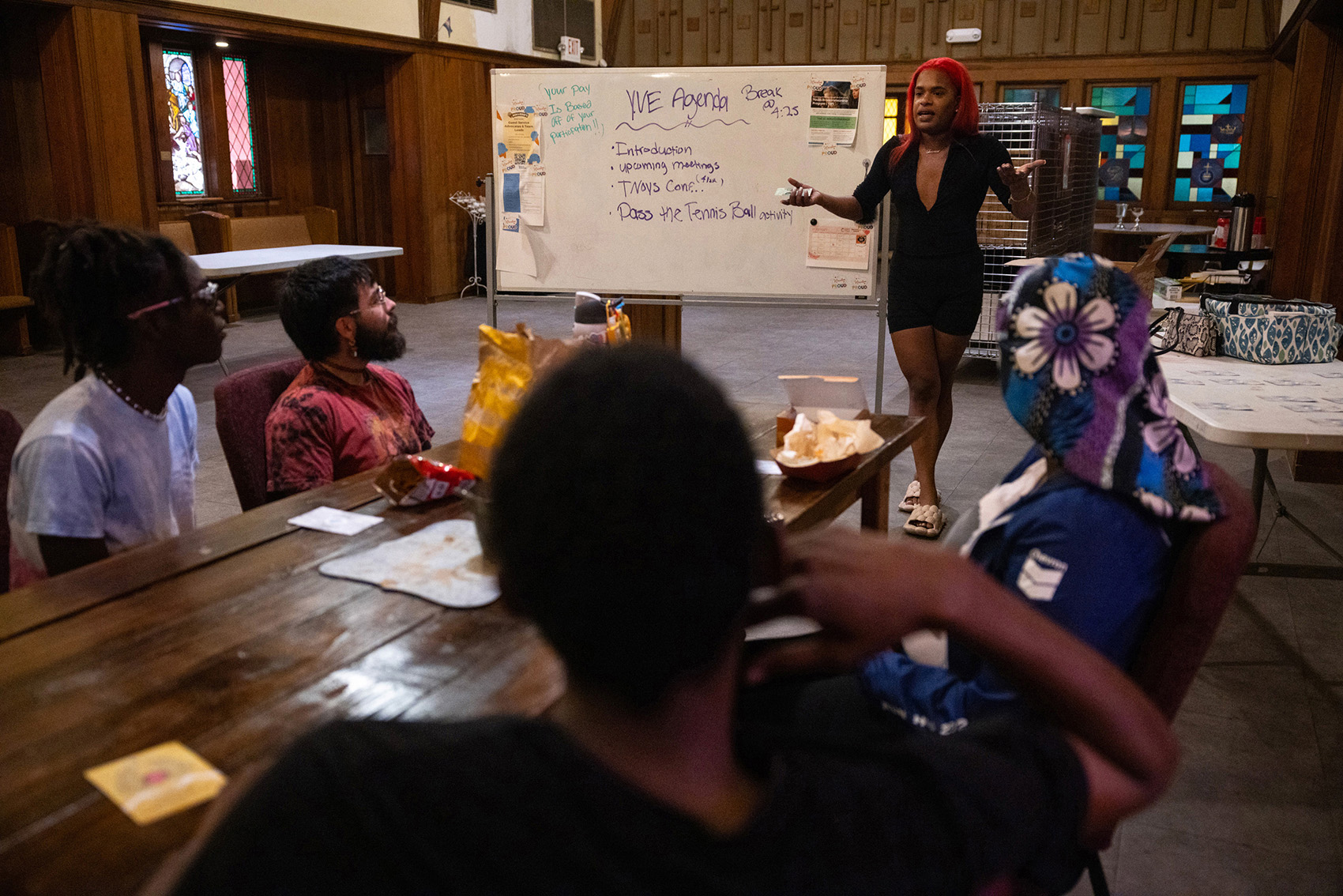

(Top left) Brandon Williams looks at a positive affirmation card during a Youth Voices Empowered event at Montrose Grace Place on May 1 in Houston. Williams was suspended multiple times from Houston ISD's Yates High School while he was homeless. (Top right) Williams plays a group game during a Youth Voices Empowered gathering. (Bottom left) Kenny Easley leads a discussion during a Youth Voices Empowered event. (Bottom right) Alicia Bain, at left, and Williams hug and laugh during a Youth Voices Empowered gathering. (Antranik Tavitian / Houston Landing)

(Top left) Brandon Williams looks at a positive affirmation card during a Youth Voices Empowered event at Montrose Grace Place on May 1 in Houston. Williams was suspended multiple times from Houston ISD's Yates High School while he was homeless. (Top right) Williams plays a group game during a Youth Voices Empowered gathering. (Bottom left) Kenny Easley leads a discussion during a Youth Voices Empowered event. (Bottom right) Alicia Bain, at left, and Williams hug and laugh during a Youth Voices Empowered gathering. (Antranik Tavitian / Houston Landing)

Former HISD teacher and soccer coach Sakis Brown poses in front of some his teaching and coaching awards, Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023, in Richmond. (Douglas Sweet Jr. for Houston Landing)

Former HISD teacher and soccer coach Sakis Brown poses in front of some his teaching and coaching awards, Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023, in Richmond. (Douglas Sweet Jr. for Houston Landing)