Pig farmer dreamed of first ever profit — then Trump's cuts hit

Two piglets jostled in the barnyard as Jess D'Souza stepped outside. Neither youngster seemed to be winning their morning game of tug-of-war over an empty feed bag.

Jess approached the chicken coop. She swung open the weathered door. The flood of fowl scampered up a hill to a cluster of empty food bowls.

Groans resembling bassoons and didgeridoos leaked from the hog house as groggy pigs stirred. Jess often greets them in a singsong as she completes chores.

Hi Mama! Hi babies!

She asks if she can get them some hay. Or perhaps something to drink? The swine respond with raspy snorts and spine-rattling squeals.

Jess unfurled the hose from the water pump as pigs trudged outdoors into their muddy pen.

“Is everybody thirsty? Are you all thirsty? Is that what’s going on?”

That morning, Jess slipped a Wisconsin Farmers Union beanie over her dark brown hair and stepped into comfy gray Dovetail overalls — “Workwear for Women by Women.” The spring wind was still crisp. Bare tree branches swayed across the 80-acre farm.

She filled a plastic bucket, then heaved the water over a board fence into a trough.

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm, pours water for pigs at Wonderfarm during her morning chores, April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. She knows she shouldn’t view her pigs like pets, but she coos at them when she works. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm, pours water for pigs at Wonderfarm during her morning chores, April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. She knows she shouldn’t view her pigs like pets, but she coos at them when she works. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)Growing up, the Chicago native never imagined a career rearing dozens of Gloucestershire Old Spots pigs in Klevenville, Wisconsin — an agricultural enclave surrounded by creeping neighborhoods of the state’s capital and surrounding communities.

She can watch the precociously curious creatures from her bedroom window much of the year. Their skin is pale, dotted with splotchy ink stains. Floppy ears shade their eyes from the sun like an old-time bank teller’s visor.

Jess spends her days tending to the swine, hoisting 40-pound organic feed bags across her shoulder and under an arm. Some pigs lumber after her, seeking scratches, belly rubs and lunch. Juveniles dart through gaps in the electric netting she uses to cordon off the barnyard, woods and pastures up a nearby hill.

She knows she shouldn’t view her pigs like pet dogs, but she coos at them when she works. Right until the last minute.

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm, installs new electric fencing as she prepares to move her pigs, April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. (Photos by Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm, installs new electric fencing as she prepares to move her pigs, April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. (Photos by Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)Jess hadn’t anticipated politics would so dramatically affect her farm.

Last year, Jess doubled the size of her pig herd, believing the government’s agriculture department, the USDA, would honor a $5.5 million grant it awarded to Wisconsin.

Under the Biden administration, the agency gave states money for two years to run the Local Food Purchase Assistance program, or LFPA, which helped underserved farmers invest in local food systems and grow their businesses.

In Wisconsin, the state, Indigenous tribes and several farming groups developed a host of projects that enabled producers to deliver goods like plump tomatoes and crisp emerald spinach to food pantries, schools and community organizations across all 72 counties.

The Trump administration gutted the program in March, just as farmers started placing seed orders. For her part, Jess must anticipate the size of her pork harvests 18 months in advance. She banked on program funding as guaranteed income.

This was supposed to be the year Jess, 40, broke a profit after a decade of toiling. She has never paid herself.

Jess chuckles as she admits she worries too much. She’s an optimist at heart but mulls over questions that lack ready-made answers: How will she support herself following her recent divorce? How are her son and daughter faring during their tumultuous teens? How will she keep the piglets from being squished by the adults?

Now, if she can’t find buyers for the four tons of pork she expects to produce, will she even be able to keep farming?

The world, she thinks, feels like it’s on fire.

A piglet nurses at Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

A piglet nurses at Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)***

In childhood, Jess, the elder sibling, strove to meet her parents’ expectations. School was her top priority. Academic achievement would lead to a good job, material comfort and happiness. She realized only as an adult that her rejection of this progression reflected a difference in values, not a personal deficiency.

She almost taught high school mathematics after college, but didn’t like forcing lukewarm students to learn.

Jess D'Souza, who raises Gloucestershire Old Spots pigs at Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., looks out the window of her home on April 8, 2025. She doubled the size of her pig herd last year, believing the federal government would honor a $5.5 million grant it awarded to Wisconsin. But it didn't. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D'Souza, who raises Gloucestershire Old Spots pigs at Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., looks out the window of her home on April 8, 2025. She doubled the size of her pig herd last year, believing the federal government would honor a $5.5 million grant it awarded to Wisconsin. But it didn't. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)Jess moved in 2005 to Verona, Wisconsin, where she planted fruit trees and vegetable gardens in her suburban yards. But a yard can only produce so much. She wanted chickens and ducks and perennial produce.

Jess can’t pinpoint a precise moment when she decided to farm pigs.

She attended workshops where farmers raved about Gloucestershires. The mamas attentively care for their offspring. Jess wouldn’t have to fret that the docile creatures would eat her own kids. Pigs also are the source of her favorite meats, and the breed tastes delicious. Her housemate wanted to harvest one.

It took almost 3 ½ years to name the farm after Jess and her then-husband located and purchased the property in 2016.

She hiked it during a showing and discovered a creek and giant pile of sand in the woods that for her children could become the best sandbox ever.

What did the place encapsulate, she mused.

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., pets Candy, a female breeding pig, while installing new fencing as she prepares to move her pigs on April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., pets Candy, a female breeding pig, while installing new fencing as she prepares to move her pigs on April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)She chronicled life on “Yet to be Named Community Farm” across social media: Photographs of piglets wrestling in straw piles next to lip-smacking pork entrees.

Also, lessons learned.

“I like to tell people I’m a recovering perfectionist, and farming is playing a large part in that recovery,” Jess posted to Facebook. She can’t develop the perfect plan in the face of unpredictability. Farmers must embrace risk. Maybe predators will infiltrate the hen house, the ends of a fence don’t quite align or a mama will crush her litter.

On the farm, life and death meet.

Some days, Jess can only keep the dust out of her eyes and her wounds bandaged.

Years later, the creatures living on the land still insist she take a moment to pause.

Jess once encountered a transparent monarch chrysalis. She inspected the incubating butterfly’s wings, noticing each tiny gold dot.

The farm instills a sense of wonderment.

When the idea for a name emerged, she knew.

Wonderfarm.

***

In March, a thunderstorm crashed overhead, and Jess couldn’t sleep. Clicking through her inbox at 5 a.m., she had more than five times her usual emails to sift through.

The daily stream of news from Washington grew unbearable. Murmurings that LFPA might be cancelled had been building.

President Donald Trump’s administration wasted no time throttling the civil service since he took office in January. Billionaire Elon Musk headed a newly created Department of Government Efficiency that scoured offices and grants purportedly seeking to unearth waste and fraud.

The executive branch froze payments, dissolved contracts and shuttered programs. Supporters cheered a Republican president who promised to finally drain the swamp. Detractors saw democracy and the rule of law cracking under hammer blows.

Wonderfarm’s silo stands above the farm on April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Wonderfarm’s silo stands above the farm on April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)But agriculture generally gleans support from both sides of the aisle, Jess thought. Although lawmakers disagree over who may claim to be a “real” farmer versus a mere hobbyist, surely the feds wouldn’t can the program.

Like the lightning overhead, the news shocked.

LFPA “no longer effectuates agency priorities,” government officials declared in terse letters sent to states and tribes.

Its termination left Jess and hundreds of producers and recipients in a lurch. The cut coincided with ballooning demand at food banks and pantries while congressional Republicans pushed legislation to shrink food assistance programs.

LFPA is a relic of a bygone era, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said in May.

She smiled as she touted the administration’s achievements and defended agency reductions before congressional appropriations subcommittees.

Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., pressed the secretary, asking if the department will reinstate “critical” food assistance programs. One in five Wisconsin children and one in 10 adults — often elderly, disabled or employed but struggling — are unable to or uncertain how they will obtain enough nutritious food.

“Those were COVID-era programs,” Rollins said, shaking her head. “They were never meant to go forever and ever.”

But LFPA also strengthened local food infrastructure, which withered on the vine as a few giant companies — reaching from fields to grocery aisles — came to dominate America's agricultural sector.

The pandemic illustrated what happens when the country’s food system grinds to a halt. Who knows when the next wave will strike?

***

Nearly 300 Wisconsin producers participated in LFPA over two years. A buyer told Jess their organization could purchase up to $12,000 of pork each month — almost as much as Jess previously earned in a year.

Wisconsin’s $8 million award was among the tiniest of drops in the USDA’s billion-dollar budget. The agency’s decision seemed illogically punitive.

Only a few months earlier, Biden’s agriculture department encouraged marginalized farmers and fishers to participate so underserved communities could obtain healthy and “culturally relevant” foods like okra, bok choy and Thai chilis.

Then the Trump administration cast diversity, equity and inclusion programs as “woke” poison.

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., looks through stored meat in her basement after finishing the morning chores on April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., looks through stored meat in her basement after finishing the morning chores on April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)Cutting LFPA also clashes with Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Make America Healthy Again initiative and his calls to ban ultra-processed foods. Farmers and distributors wondered what goods pantries would use to stock shelves instead of fresh produce. Boxed macaroni?

The aftershocks of the canceled award spread through Wisconsin’s local food distribution networks. Trucks had been rented, staff hired and hub-and-spoke routes mapped in preparation for three more years of government-backed deliveries.

For a president who touts the art of the deal, pulling the plug on an investment that neared self-sufficiency is just bad business, said Tara Turner-Roberts, manager of the Wisconsin Food Hub Cooperative.

Democratic Gov. Tony Evers accused the Trump administration of abandoning farmers, and Attorney General Josh Kaul recently joined 20 others suing to block grant rescissions.

Meanwhile, participants asked the agriculture department and Congress to reinstate the program. Should that fail, they implored Wisconsin legislators to fill the gap.

Meanwhile, participants asked the agriculture department and Congress to reinstate the program. Should that fail, they implored Wisconsin legislators to fill the gap and continue to seek local solutions.

Jess is too.

***

Jess alternately texted on her cellphone and scanned a swarm of protesters who gathered across the Wisconsin State Capitol’s lawn.

She had agreed to speak before hundreds, potentially thousands, of people and was searching for an organizer.

Madison’s “Hands off!” rally reflected national unrest that ignited during the first 75 days of Trump’s term. In early April, a coalition of advocates and civil rights groups organized more than 1,300 events across every state.

Jess D’Souza, a farmer raising heritage pigs at Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., delivers a speech on April 5, 2025, at the "Hands off!" protest in downtown Madison. She is one of nearly 300 Wisconsin growers who over two years participated in the Local Food Purchase Assistance program, which the Trump administration canceled. (Bennet Goldstein / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D’Souza, a farmer raising heritage pigs at Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., delivers a speech on April 5, 2025, at the "Hands off!" protest in downtown Madison. She is one of nearly 300 Wisconsin growers who over two years participated in the Local Food Purchase Assistance program, which the Trump administration canceled. (Bennet Goldstein / Wisconsin Watch)Jess pulled out a USDA-branded reusable sandwich bag, which she had loaded with boiled potatoes to snack on. She and her new girlfriend joined the masses and advanced down State Street to the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus.

A hoarse woman wearing a T-shirt covered in peace patches and a tie-dye bandana directed the marchers. She led them in a menagerie of greatest protest hits during the 30-minute walk past shops, restaurants and mixed-use high-rises.

“Money for jobs and education, not for war and corporations!” her metallic voice crackled through a megaphone.

Trump’s administration had maligned so many communities, creating a coherent rallying cry seemed impossible. The chant leader hurriedly checked her cellphone for the next jingle in a dizzying display of outrage.

“The people, united, will never be defeated!”

“Say it loud! Say it clear! Immigrants are welcome here!”

Jess leaned into her girlfriend, linking arms as they walked.

They ran into a friend with violet hair. Jess grinned sheepishly, trying not to think about the speech.

“You’ll be fine,” her friend said.

The chant captain bellowed.

“Hands off everything!”

A black police cruiser flashed its emergency lights as the walk continued under overcast skies.

An hour later, Jess stood atop a cement terrace, awed by the sea of chatter, laughter and shouts that swamped the plaza.

A friend took her photo. Jess swayed to the chant of “Defund ICE!” A protester walked past, carrying a sign bearing the silhouette of Trump locking lips with Russian President Vladmir Putin.

Someone passed Jess a microphone. The crowd shouted to the heavens that “trans lives matter!” A cowbell clanged.

She grinned.

“I don’t want to slow us down,” Jess began.

She described her dilemma as the crowd listened politely. The government broke its commitments. She struggles to pay bills between unpredictable sales. Some farm chores require four working hands.

Jess only has two.

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm, installs new fencing as she prepares to move her pigs, April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. This was supposed to be the year Jess broke a profit after a decade of toiling. But cuts to a federal program jeopardize those plans. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm, installs new fencing as she prepares to move her pigs, April 8, 2025, in Klevenville, Wis. This was supposed to be the year Jess broke a profit after a decade of toiling. But cuts to a federal program jeopardize those plans. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)“LFPA kind of gave me hope that I'd be able to keep doing the thing that I love,” she said.

Bystanders booed as she recounted the night of the fateful email. Jess chuckled and rocked on her foot, glad to see friends in the audience.

“The structures around us are crumbling,” she said, shrugging. “So let's stop leaning on them. Let's stop feeding them. Let’s grow a resilient community.”

The crowd whooped.

***

It’s hard for Jess to stomach meat on harvest days.

Naming an animal and later slaughtering it necessitates learning how to grieve. Jess had years to practice.

The meat processor’s truck rumbled up the farm driveway at 7 a.m. in late April.

Jess spent the previous week sorting her herd, selecting the six largest non-breeding swine. She ushered them to either side of a fence that bisected the barnyard.

It took roughly 30 minutes for the two butchers to transform a pig into pork on Jess’ farm. The transfiguration occurred somewhere between the barnyard, the metal cutting table and the cooler where the halved carcasses dangle from hooks inside the mobile slaughter unit.

Mitch Bryant of Natural Harvest butchering uses an electrical stunner on a pig on April 29, 2025 — harvest day at Jess D’Souza's Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis. Electricity causes the animal to seize and pass out before butchers cut into it. (Patricio Crooker for Wisconsin Watch)

Mitch Bryant of Natural Harvest butchering uses an electrical stunner on a pig on April 29, 2025 — harvest day at Jess D’Souza's Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis. Electricity causes the animal to seize and pass out before butchers cut into it. (Patricio Crooker for Wisconsin Watch)The butchers unpacked their gear in the gentle morning glow. Jess carried a plastic tray of eggs, squash shavings and mango peels to the pen.

The snack helps lure anxious pigs during the harvest. It’s also a final gift for the one they are about to give.

The butchers employed an electrical stunner that resembles a pair of barbecue tongs. A coiled cord connects the contraption to a battery that releases an electric current.

When pressed to a pig’s head, the animal seizes and passes out. The butchers cut its chest before it awakens.

An hour into the harvest, Jess guided more swine from a trailer, where a cluster slept the previous night, along with a seventh little pig that wasn’t headed to the block.

A male began to urinate atop a dead female — possibly mating behavior. Jess smacked his butt to shoo him away. She regretted it.

He bolted across the yard, grunting and sidestepping whenever Jess approached.

“Just leave him for the next round,” one of the butchers said.

Shaun Coffey of Natural Harvest butchering works at Jess D’Souza's pig farm in the unincorporated community of Klevenville, Wis., on April 29, 2025. (Patricio Crooker for Wisconsin Watch)

Shaun Coffey of Natural Harvest butchering works at Jess D’Souza's pig farm in the unincorporated community of Klevenville, Wis., on April 29, 2025. (Patricio Crooker for Wisconsin Watch)Jess remembers her first on-farm slaughter years ago when a female spooked and tore through the woods. Jess kept her as a breeder.

The agitated male disappeared behind the red barn. He sniffed the air as he peeked around the corner.

The standoff lasted another hour. One of the butchers returned with a 20-gauge shotgun. He unslung it from his shoulder, then walked behind the building.

Jess turned away. She covered her ears. A rooster crowed.

The crack split the air.

The other worker hauled the pig across the barnyard, leaving a glossy wake in the dirt.

Jess crossed the pen, shoulders deflated, and stepped over the dividing fence to feed the others.

A 6-month-old trotted over to her. Jess squatted on her haunches and extended a gloved hand.

“Are you playing?” she asked. “Is that what is happening?”

Farmer Jess D'Souza greets a pig at Wonderfarm in the unincorporated community of Klevenville, Wis., on April 29, 2025 — a harvest day. (Patricio Crooker for Wisconsin Watch)

Farmer Jess D'Souza greets a pig at Wonderfarm in the unincorporated community of Klevenville, Wis., on April 29, 2025 — a harvest day. (Patricio Crooker for Wisconsin Watch)***

The May harvest never happened.

Nearly all the females were pregnant, even though they aren’t designated breeders. Jess will postpone the slaughter day for now.

She needs to decide whether to raise her spring piglets or sell them. It all depends on how quickly she can move product, but she’s leaning toward keeping them.

The pork from April’s butchering is on ice as she works her way down a list of potential buyers. She still serves people in need by selling a portion to a Madison nonprofit that distributes Farms to Families “resilience boxes.”

Jess marks the days she collects her meat from the processor. She defrosts, say, a pack of brats and heats them up for dinner.

She celebrates her pigs.

Jess and her farming peers are planning for a world with less federal assistance.

One idea: They would staff shifts at the still-under-construction Madison Public Market, where fresh food would remain on site 40 hours a week. No more schlepping meat from cold storage to a pop-up vendor stand.

She dreams of a wholesale market where buyers place large orders. One day maybe. No government whims or purse strings.

Like seeds that sprout after a prairie burn, some institutions will survive the flames, she thinks. Perhaps it doesn’t have to be the ones in Washington.

Those that remain will grow anew.

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., retrieves a bale of hay for one of her “mama pigs” during morning chores, April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Jess D'Souza, owner of Wonderfarm in Klevenville, Wis., retrieves a bale of hay for one of her “mama pigs” during morning chores, April 8, 2025. (Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)This story is part of a partnership with the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an editorially independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri School of Journalism in partnership with Report for America and funded by the Walton Family Foundation.

Wisconsin Watch is a member of the Ag & Water Desk network. Sign up for our newsletters to get our news straight to your inbox.

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

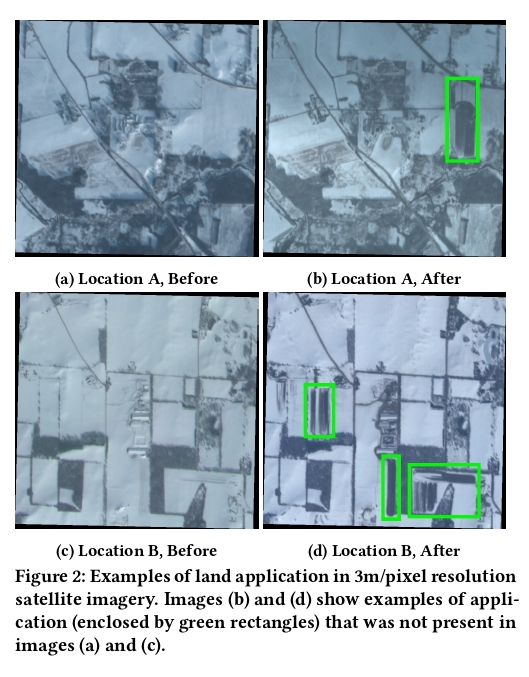

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources contacted Weiss Family Farms in Durand, Wis., after the dairy operation spread solid manure on a field the week prior. A machine learning model developed by researchers at Stanford University’s Regulation, Evaluation and Governance Lab initially flagged Weiss’ field, shown here, to the state agency as an area where manure was spread during prohibited winter months. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources contacted Weiss Family Farms in Durand, Wis., after the dairy operation spread solid manure on a field the week prior. A machine learning model developed by researchers at Stanford University’s Regulation, Evaluation and Governance Lab initially flagged Weiss’ field, shown here, to the state agency as an area where manure was spread during prohibited winter months. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

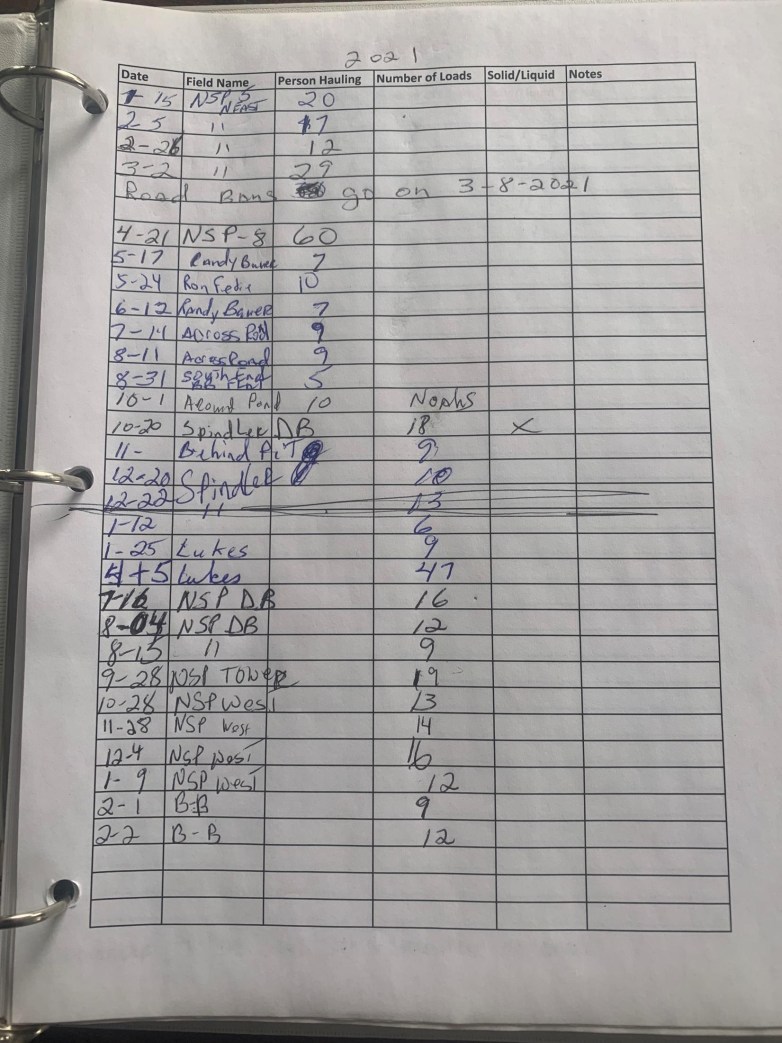

Manure spreading logs of Weiss Family Farms in Durand, Wis., are shown in a Feb. 10, 2023, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources report. The report concluded that the farm had spread manure during a high-risk runoff period spanning February and March.

Manure spreading logs of Weiss Family Farms in Durand, Wis., are shown in a Feb. 10, 2023, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources report. The report concluded that the farm had spread manure during a high-risk runoff period spanning February and March.