Shameless hypocrites: Conservatives cry wolf over deficit spending -- after being wrong again and again

Predictably, conservatives are once again warning about inflation. This happens every time a Democrat takes office—even if he merely continues the identical policies of his Republican predecessor.

Unfortunately, these concerns, which always receive wide media attention, are costly both politically and economically.

Bill Clinton was forced to adopt a deficit reduction plan in 1993 that led to the defeat of many Democrats in 1994 and the installation of Newt Gingrich as speaker of the House.

Barack Obama was forced to scale back his stimulus plan in 2009 and was browbeaten into deficit reduction in 2011. That kept the economy running in slow gear throughout Obama's presidency paving the way for Donald Trump.

We have paid a heavy price for believing the conservatives who cried wolf about inflation year after year without any evidence supporting their predictions.

Now that Joe Biden has gotten his stimulus, the inflation-mongers are just getting started again.

Criticism of COVID-19 Relief

Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), citing economist Larry Summers, offered a representative reaction in the wake of the American Rescue Plan Act's passage:

"America's economy is improving, and the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said recently that the economy will recover to pre-pandemic levels by mid-year without any additional stimulus.

"This makes it even more troubling that Democrats have passed this partisan and expensive bill that one prominent Democratic economist says could overheat an already recovering economy and lead to higher inflation, hurting middle-class families and threatening long-term growth."

It's been an article of faith among conservatives since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008 that inflation is right around the corner.

This conviction follows from a core conservative belief that inflation invariably results from increases in the money supply. As Milton Friedman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist put it a half-century ago in an oft-quoted line: "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

Thus, when the Federal Reserve vastly expanded the money supply in late 2008, conservatives anticipated a sharp rise in inflation. It didn't happen.

Fixing the Financial Crisis

In 2009, many prominent conservative economists confidently predicted an imminent rise in inflation. Here's a representative sample:

- John Taylor, Stanford: "There is no question that this enormous increase from $8 billion to $3,365 billion [increase in the money supply] will lead to higher inflation unless it is reversed."

- Martin Feldstein, Harvard: "The unprecedented explosion of the US fiscal deficit raises the specter of higher future inflation."

- Arthur Laffer, economic consultant: "To date what's happened is potentially far more inflationary than were the monetary policies of the 1970s."

- Alan Greenspan, former Federal Reserve Board chairman: "Statistical analysis suggests the emergence of inflation by 2012."

Indeed, many Republicans predicted not just inflation, but hyperinflation.

- Rep. Dan Burton of Indiana said: "We are heading toward hyperinflation again."

- Sen. John McCain of Arizona said: "My great worry is that if we do not account for this debt in some way, if we continue trillions of dollars of unnecessary and wasteful spending, then obviously we will find ourselves back in the situation we were in the 1970s when we had hyperinflation and had to debase the currency."

- Rep. Paul Broun of Georgia warned: "I think we're fixing to head for hyperinflation."

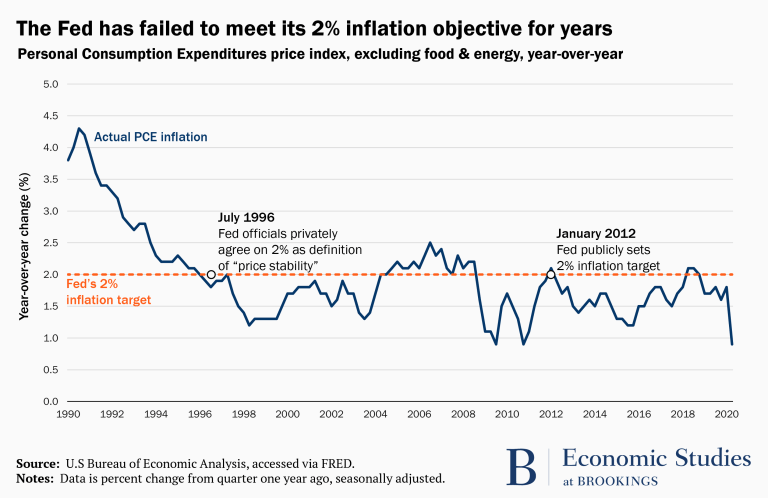

Yet, year after year, there was no inflation. In 2009 we saw prices fall slightly, the opposite of these predictions and warnings. The Federal Reserve couldn't even hit its own target of 2% inflation. The average inflation rate for 2009 through 2020 was less than 1.3% annually.

That did nothing to dislodge right-wing orthodoxy, however. Conservatives continue to say that inflation was right around the corner. No amount of empirical data could shake their deeply held belief.

A Decade Ago

On Nov. 15, 2010, a group of conservatives—including reputable economists such as Michael Boskin, Ronald McKinnon and John Taylor, all of Stanford, as well as various Wall Street analysts and journalists—published an open letter to Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, a Republican originally appointed by George W. Bush. The letter said:

We believe the Federal Reserve's large-scale asset purchase plan (so-called "quantitative easing") should be reconsidered and discontinued. We do not believe such a plan is necessary or advisable under current circumstances. The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed's objective of promoting employment.

We subscribe to your statement in The Washington Post on November 4 that 'the Federal Reserve cannot solve all the economy's problems on its own.' In this case, we think improvements in tax, spending and regulatory policies must take precedence in a national growth program, not further monetary stimulus.

We disagree with the view that inflation needs to be pushed higher, and worry that another round of asset purchases, with interest rates still near zero over a year into the recovery, will distort financial markets and greatly complicate future Fed efforts to normalize monetary policy.

The Fed's purchase program has also met broad opposition from other central banks and we share their concerns that quantitative easing by the Fed is neither warranted nor helpful in addressing either U.S. or global economic problems.

Nevertheless, the concerns of conservatives were not absurd—up to a point. It was possible that the time lag between rises in the money supply and inflation had been lengthened by the recession. Unless the fundamental relationship between the money supply and inflation that every conservative had taken to heart in the 1970s was completely wrong, higher inflation was still in the pipeline.

The real problem was that none of the traditional indicators suggested anything like a serious inflation threat was on the horizon.

Years after the beginning of quantitative easing there were still no signs of inflation in any commonly used index and interest rates remain low. Even the price of gold, which many conservatives view as the most accurate measure of future inflation, has fallen sharply from its peak of close to $2,000 per ounce in late 2011 to about $1,200 per ounce in 2014 and about $1,700 today.

And Now

At this point, a reasonable person would be forced to admit that predictions of high inflation were based on faulty theory. Yet, few of those who signed the letter to Bernanke owned up to any doubts when queried by Bloomberg News in October 2014. It is worth quoting them at length.

—Jim Grant, publisher of Grant's Interest Rate Observer, in a phone interview:

"People say, you guys are all wrong because you predicted inflation and it hasn't happened. I think there's plenty of inflation—not at the checkout counter, necessarily, but on Wall Street.

"The S&P 500 might be covering its fixed charges better, it might be earning more Ebitda [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization], but that's at the expense of other things, including the people who saved all their lives and are now earning nothing on their savings."

"That to me is the principal distortion, is the distortion of the credit markets. The central bankers have in deeds, if not exactly in words — although I think there have been some words as well — have prodded people into riskier assets than they would have had to purchase in the absence of these great gusts of credit creation from the central banks. It's the question of suitability."

—John Taylor, professor of economics at Stanford University, in a phone interview:

"The letter mentioned several things – the risk of inflation, employment, it would destroy financial markets, complicate the Fed's effort to normalize monetary police – and all have happened."

"This is the slowest recovery we've ever had. Working-age employment is lower now than at the end of the recession."

"Where is the evidence that it worked? It's just not there."

—Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former director of the Congressional Budget Office, in a phone interview:

"The clever thing forecasters do is never give a number and a date. They are going to generate an uptick in core inflation. They are going to go above 2%. I don't know when, but they will."

—Niall Ferguson, Harvard University historian and author of The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, referred Bloomberg News to a blog post he wrote in December 2013, saying his thoughts haven't changed:

"Though generally regarded by a cause for celebration (even by those commentators who otherwise lament increasing inequality), this bull market has been accompanied by significant financial market distortions, just as we foresaw."

"Note that word 'risk.' And note the absence of a date. There is in fact still a risk of currency debasement and inflation."

—David Malpass, former deputy assistant Treasury secretary [now president of the World Bank], in a phone interview:

"The letter was correct as stated."

"I've observed that credit is flowing heavily to well-established borrowers. This has worsened income inequality and asset inequality going on in the economy. You're looking at the companies that got credit. The problem is the new businesses that didn't get credit. The facts are that private sector credit growth has been slow. It is a zero-sum process where each corporate bond issue was money that otherwise might have gone to a new business or a small business."

—Amity Shlaes, chairman of the Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation, wrote in an e-mail:

"Inflation could come, and many of us are concerned that the nation is not prepared."

"The rule with inflation is 'first do no harm.' So you always want to be careful."

—Peter Wallison, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, in a phone interview:

"All of us, I think, who signed the letter have never seen anything like what's happened here."

"This recovery we've had since the end of 2009 has been by far the slowest we've had in the last 50 years."

—Geoffrey Wood, a professor emeritus at City University London's Cass School of Business, in a phone interview:

"I think everything has panned out. We should probably be more cautious about the timing. Economists should always be cautious about the timing. Timing is close to totally unpredictable."

"The economy is growing. If the Fed doesn't ease money growth into it, inflation could arrive."

—Richard Bove, an analyst at Rafferty Capital Markets LLC, in a phone interview:

"If interest rates are low, it means a large portion of the population was made poor because passive income declined."

"If you take a look at the economy, I think that the economy has grown in line with the growth in population and the growth in income. I would argue that the bulk of this QE money never reached the economy."

"Someone's got to prove to me that inflation did not increase in the areas where the Fed put the money. We know where they put the money. And we know where they put the money prices went up dramatically. And we also know the consumer price index does not pick up either of those price increases. Housing prices are not in the CPI and fixed income prices are not in the CPI. So how do you know that QE benefited the economy?"

It's now 2021 and none of these dire inflation predictions from 2010 or 2014 has come to pass.

I don't know if there has been a permanent change in the relationship between the money supply and inflation, as some advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) claim.

But I do know that we have paid a heavy price for believing the conservatives who cried wolf about inflation year after year without any evidence supporting their predictions.

At the very least, we should treat their current concerns with deep skepticism. And they should admit they were wrong in 2010 and 2014 and offer some explanation for why. I've never heard one.