Originally published by The 19th. Subscribe to The 19th's daily newsletter.

In 2014, states were required to begin reporting how many children die, are injured or abused in child care. Some still aren’t. For parents who have lost children, it’s proof that the system isn’t working.

Doubts swirled from the start.

After Cynthia King’s baby Wiley Muir died suddenly at a home-based day care in Honolulu, she fixated on the things that seemed off. The medical examiner said he died of pneumonia, but Wiley hadn’t been sick that morning. King wondered how sickness could take him so suddenly — how they could have missed that.

But most of all, there was the notebook, which King began keeping just four days earlier, when Wiley started at the day care. On the morning of February 6, 2014, King had jotted down what time her 4-month-old had woken up and what he’d eaten. That notebook had gone with Wiley to day care that morning and was returned to King at the police department days after his death.

The page she’d started the day he died was gone, ripped out. Instead, there was a new page rewritten in the day care owner’s handwriting.

“That freaked me out. Why on Earth, on the day he died, would the day care provider rip out the page and rewrite what I had already started writing?” King said.

A year and a half later, on what would have been Wiley’s second birthday, King and her husband ran into Therese Manu-Lee, the provider caring for Wiley when he died. She was wearing scrubs and appeared to be working with an elderly person. King wondered what happened to the day care.

Later, King looked her up online. The day care had been shut down by the state.

Right away, King called the Department of Human Services, which oversees the state’s child care office. Manu-Lee’s license was suspended while police investigated Wiley’s case but reinstated when the case was closed. It was shut down again a year later in 2015 when a surprise inspection of Manu-Lee’s home found her with 14 children in her care, eight of them infants — four times the legal number of infants for a home-based provider.

The doubts rushed back.

“That sort of overwhelming feeling of, ‘Oh my God, I knew she was lying to us about something, but I didn’t know what’” took over, King said.

That revelation set in motion years of battles: first with the police department to reopen Wiley’s case, and then with the state’s child care agency and the Hawaii legislature to push for new legislation that could make child care safer.

Beginning in 2016, King, an entomologist, sat on a Hawaii child care working group in the legislature and advocated for about a dozen regulation bills. But she could get only one new law through — an update requiring day cares to take on liability insurance. The Wiley Kaikou Muir Act passed in 2017.

Cynthia King reads to her son Dexter Muir at their home in Honolulu, Hawaii, in 2016. (CORY LUM/CIVIL BEAT)

Cynthia King reads to her son Dexter Muir at their home in Honolulu, Hawaii, in 2016. (CORY LUM/CIVIL BEAT)

Among King’s larger priorities was passing a law requiring Hawaii to post child care inspection violations online and track serious incidents, creating a window into the state’s child care safety efforts. But King was told at the time by state officials that Hawaii didn’t need that law — a child care safety movement at the federal level was about to do just that.

In 2014, the same year Wiley died, the country’s central funding mechanism for child care, the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), was reauthorized by Congress with new requirements. CCDBG sends money to states to subsidize care for low-income children, and because every state takes CCDBG money, they all have to comply with its rules.

Until 2014, the block grant had paltry health and safety requirements. States didn’t have to run background checks on child care providers or collect data on deaths or serious incidents.

So no one knew, really, how many kids were getting hurt at child care across the country — how many were dying.

Although child care was and still is very safe, cases of children dying in day cares from preventable causes started to gain national attention in the early 2000s. That helped advocates launch what would become a nearly decade-long campaign in Congress to weave better health and safety guidelines into CCDBG.

New requirements passed into law with broad bipartisan support in 2014. Among them: For the first time, states would be required to start collecting and posting data around the numbers of deaths, serious injuries and substantiated abuse cases at day cares. Databases also needed to go online, allowing parents to search providers and see inspection reports and violations in their state. A series of federal, state and interstate background checks were also made mandatory. States had until October 2018 to come into compliance.

Ten years after those rules around health and safety were put in place, over a dozen states are failing to fulfill all the reporting requirements, an in-depth analysis from The 19th found.

After an inquiry from The 19th, the Office of Child Care, the federal regulatory agency that oversees states’ child care systems, confirmed that eight states are out of compliance. The 19th found an additional eight states that are missing data or have outdated information online. Six states updated their reports when The 19th pointed out errors or missing data.

In the process of reporting this story, The 19th reached out to more than 40 advocates, experts and organizations in the child care and child welfare space. Few knew anything about where the states stood on the reporting requirements in CCDBG. Some didn’t know about the requirements at all.

Linda Smith, a child care expert who was instrumental in getting the regulations passed, said states have been given too much latitude to comply. Neither the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Health and Human Services nor the Government Accountability Office have audited the states to ensure they were following the reporting provisions, both offices confirmed.

“For the most part, they are sort of operating outside of the traditional system and accountability,” said Smith, now the director of the early childhood development initiative at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a nonpartisan think tank.

Systems like background checks and data tracking are key safety mechanisms in any industry. Food service inspection violations are posted online and in restaurants. Accidents with airlines are also posted online, even though, like in child care, they are also fairly rare.

Overall, the number of deaths at day cares is very low, often in the single digits annually in each state, and some states haven’t had any at all for the past several years. Among the 30 states and Washington, D.C., that published 2023 data, California had the highest number of deaths last year: 10; one child died at a child care center and nine died at in-home day cares. The two states with the next highest numbers last year were Texas at six deaths and Montana with five.

Data on injuries and abuse is murkier. States can decide how they define these cases — some count any instance that requires medical attention, others count only injuries that cause permanent damage — leading to widely different numbers. Georgia, for example, had zero serious injuries in 2022; Ohio, which also counts serious “incidents,” had nearly 19,000.

There is also no federal reporting requirement, meaning the data lives at the state level, in reports that are difficult to find and, in some cases, difficult to understand.

Celia Sims, a former senior staffer for Sen. Richard Burr, the North Carolina Republican who spearheaded the changes to CCDBG, said they took on the issue more than 10 years ago because tallying cases is one of the only ways to ensure safety for really young kids.

“You can’t count on your 6-month-old to tell you that something is wrong when you pick them up in the evening,” Sims said. “That’s why it’s even more important that things, when they are substantiated, get reported.”

The intent behind the requirements was also to create transparency for parents. But Sims said she’s been surprised to discover just how hard it is to even find the information. Most reports are buried in state websites, under titles like “aggregate report” or “federal reporting,” and hyperlinked in the middle of a paragraph. It’s not the easily accessible, plain language vision that was laid out in CCDBG.

“I was a little taken aback,” said Sims, who went on to found The Abecedarian Group, a child care and education consulting agency. “Wow, I couldn’t find any of them.”

The reporting requirements aren’t the only issue. More than half of states are also out of compliance with the law’s new background check requirements, which called for five checks and three interstate checks that have to be completed within 45 days for all child care staff. For home-based day cares, that also includes adults living in the house who may come in contact with children. According to a 2022 report to Congress from an interagency task force convened to study the issue, 11 states are not conducting any interstate checks and 19 states are allowing child care staff to be hired before background checks were completed. Those numbers remain current, the Office of Child Care confirmed.

The 19th also analyzed if states had fulfilled a third requirement of creating online databases of all the state’s child care providers with inspection and violation data.

Only one state was out of compliance on all three categories: Hawaii.

Hawaii hasn’t posted any data at all from the past seven years on serious injuries and abuse at day cares. The last year it reported was 2016, making it the only state with a reporting gap that wide. The online database of violations King advocated for a decade ago — the one she was told was coming soon in 2016 — is still not up. Hawaii is also one of the states not running interstate background checks on child care providers.

The reasons why are various, but underpinning Hawaii and the other states’ compliance issues is a difficult reality. The child care system in the United States has been described by the Treasury Department as a “textbook example of a broken market.” It is losing day cares to financial constraints and a lack of federal investment. To ensure safety, day cares have to stick to strict ratios of children to teachers. That means staffing costs make up a huge portion of the budget, but that also means the staff is paid close to minimum wage, leading to high turnover. Raising wages would mean raising fees for parents, many of whom are paying more than their rent or mortgage on child care.

But when CCDBG was reauthorized, Congress did not substantially increase the program’s budget to help states implement the new safety requirements. Some of what ultimately happened was that states didn’t make safety improvements right away, Smith said. And now a decade later, some still haven’t.

None of the states have been penalized for it, the federal Office of Child Care confirmed. In Hawaii, where an extraordinarily high cost of living meets an extraordinarily low child care supply, parents don’t always report all the red flags they see at a center for fear it’ll close down and they’ll have nowhere to take their kids, King said.

That is a challenge that needs a solution, but it shouldn’t mean accountability is lost, King said. And it shouldn’t now be up to the parents whose children have already been lost to push for a better system.

“It’s so inappropriate that the onus is on the families of victims, when this should be coming from the state or federal level,” King said. “There’s something that’s really very difficult about being a group of people where everybody is not whole. That’s why nothing is happening. Because everyone is hurting tremendously.”

Until the early 2000s, very little was known at a national level about incidents at child care centers. A 2005 report by researchers at the City University of New York Graduate Center put together the first — and so far only — comprehensive national study of deaths in child care, cobbling together reports published in media outlets, legal cases and some state records.

They found 1,362 fatalities in child care from 1985 through 2003, 75 percent of them in home-based care, both licensed and unlicensed.

“Key to any effort aimed at reducing risks is gathering consistent, reliable data on fatalities, serious injuries, and near misses in child care,” they wrote.

Child Care Aware, a national child care advocacy group, then took the issue on, releasing an analysis of state rules and regulations around safety every year from 2007 to 2013. Their work paved the way for Congress to act in the 2014 reauthorization — the new rules all came from the organization’s recommendations.

Smith was the executive director of Child Care Aware at the time, and she and Grace Reef, the chief of public policy, led that effort.

“You think that licensing means something, but what we were exposing at the time was: not really,” Reef said. “There were states that did an inspection once every 10 years — are you kidding me?”

The CCDBG requirement ultimately shaped up like this: States must produce data every year on the number of deaths, serious injuries and cases of substantiated abuse at child care. The numbers for death and serious injury were to be broken down by the type of program incidents took place in — center-based or home-based, for example— and the data had to be published online and easily accessible.

Here’s where we stand, 10 years later.

As of 2024, California is the only state that still doesn’t post serious injury or abuse data online at all.

Alaska and Wisconsin don’t provide breakdowns by the type of child care facility serious injuries took place in. Vermont didn’t either for serious injuries and deaths until The 19th asked about it and, realizing an error that occurred with a change of staff, the state updated its website the next day.

Wisconsin, which failed to include data on four deaths in its 2021 report, updated it after The 19th’s questions. Wyoming, which wasn’t posting data on substantiated abuse cases, added the figures when The 19th inquired. Alaska provided additional data to The 19th via email, though it hasn’t yet made it public.

The 19th also found one state with outdated statistics: South Dakota’s most recent data is from 2021. New Hampshire hadn’t published data since 2020, but after The 19th inquired, the state posted 2023 data in January.

Delaware, Kansas and New Jersey have all been flagged by the Office of Child Care for not posting complete data on license-exempt providers. The 19th’s own analysis found that Arkansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma are not reporting data on those providers. Delaware, Kansas, Missouri and Oregon have also failed to include totals for the number of kids in child care, another required part of the regulation. Illinois was also missing that data but added it after The 19th asked.

The federal office marked Mississippi and New York as out of compliance as of the end of 2023, but both states updated most of their data online, though Mississippi still appears to be missing annual data. The federal office also flagged West Virginia for posting incomplete data on in-home providers, but the state said it hadn’t received such a notice and that it would be updating its data this month.

Even in states that are reporting data, some of it is confusing and contradictory. In Nevada, the child care division is in the process of changing departments, and that has led to two different reports online: In one published by the welfare division, the abuse cases in 2020 numbered above 3,000. In the 2020 report from the licensing department, the number of abuse case referrals is 48.

When The 19th asked about the discrepancy in Nevada’s data, Karissa Loper Machado, the state’s agency manager for child care, said she wasn’t sure how the first report was calculated. After the state looked into it, it said the data it had been publishing as its child care numbers also included cases in private homes and foster care, leading to the higher figures. The state expects to have its data updated in the next six months to a year.

Nevada also doesn’t report how many of its abuse cases turn out to be substantiated. The licensing department doesn’t keep track of it, so the state doesn’t report it.

“We are working to come into compliance,” Loper Machado said.

In the 10 years since the CCDBG reporting requirements were created, states have been given a lot of autonomy in deciding what gets counted as serious injury and abuse and what doesn’t. In 2018, the Office of Child Care told state child care agencies to consider changing their definitions so that only programs with the most egregious cases were penalized. Some states changed their definitions, and others did not.

In Georgia, cases are put on a scale — low, medium, high or extreme harm or risk — and only extreme cases now get reported, said April Rogers, the child care services director of policy and enforcement at the Georgia Department of Early Care and Learning.

Georgia lists two serious injuries in 2023, and both of those programs lost CCDBG and state funding as a result of that determination, said Ira Sudman, the department’s general counsel, and programs with “high”-level injuries can still potentially incur penalties.

By contrast, in Ohio, the state counts all serious injuries and incidents, covering everything from deaths (which get double counted) to COVID-19 cases. There were 18,788 serious injuries or incidents in Ohio in 2022, the most recent year for which there is data. Even without including COVID cases, the number is still 4,762 — at least 10 times what many other states are reporting. In early 2017, the state put in an automated reporting system that allowed day care owners to report serious incidents quickly online.

Reef said that over the years, state legislatures have battled over what they should count in the numbers. But for the data to be tracked well, there need to be requirements of day care owners, too, state child care agencies said.

All of the data on deaths, serious injuries and abuse is self-reported by the day care providers themselves typically through forms they submit to the states. The states do inspections of the providers to make sure they are following safety requirements, but several states, including Georgia and Missouri, told The 19th they don’t know how accurate those reports are because they’re relying on the day cares to submit them.

What’s missing is “political will around forcing private business to give us data they clearly do not want to give us,” said Pam Stevens, Georgia’s deputy commissioner for child care. “We would love to know everything because it would help everybody.”

In Missouri, Nancy Scherer, the administrator of the state’s Office of Childhood, said getting day cares to report is the highest hurdle they face.

“I think they’re afraid: ‘If I report that, I’m going to have a violation, they’re going to shut me down,’” Scherer said.

And those are the providers the state knows about.

In 2021, eight children died in Missouri day cares. Seven of those deaths took place in unlicensed child care, which the office isn’t tracking because it doesn’t license them. Deaths are tallied instead through tips that come in.

“We don’t know about it, until we know about it,” Scherer said.

After King learned that her son’s provider had been shut down by the state of Hawaii, she asked to see his full police case file. For the first time, she also brought herself to read his autopsy in its entirety.

Those files contained numerous inconsistencies — vindication that King had been right to have her doubts.

Manu-Lee told police Wiley was in her arms when he died, but she told the ambulance crew that she’d put him down for a nap and later found him unresponsive. And in the autopsy, Wiley’s cause of death was not pneumonia, but bronchiolitis, which affects a different part of the lungs than pneumonia.

The autopsy findings helped King push the police to reopen the case, but ultimately prosecutors told her there wasn’t really an avenue to pursue. Detectives didn’t have any evidence of abuse or trauma.

The 19th reached out to Manu-Lee via phone and email, but she did not respond to requests for comment. In 2016, she told Civil Beat that, “the child was ill. It was not my fault.”

King was, however, able to have other pediatric forensic pathologists examine Wiley’s autopsy, who determined he could not have died from bronchiolitis or pneumonia. In Honolulu, the medical examiner admitted to King, she said, that he’d put that cause of death to give her a sense of closure.

The cause of death was ultimately changed to “undetermined.”

“It was hard emotionally to have to justify to people again and again why having an incorrect cause of death provided to us was so damaging and counterproductive toward finding out what really happened,” King said. “When the cause of death was changed, in some ways it was sort of a relief.”

After her son’s untimely death, King focused on legislation. (COURTESY OF CYNTHIA KING)

King refocused on legislation, but while she waited for Hawaii to implement the requirements of the federal law, she became disheartened. By 2017, the new requirements were still not in place, and King, still pushing for new laws, pleaded with the state.

“I am asking you to change this shockingly broken system and instill real accountability,” she testified at a hearing for what would go on to be another failed child care accountability bill.

In 2019, past the deadline for states to come into compliance with federal regulations, Hawaii still hadn’t implemented the changes. King still hadn’t had more luck with legislation. And she was pregnant. By the time COVID-19 shut the world down, King realized there was no hope in pushing for changes in an industry that was being decimated by the pandemic. Nothing would pass. So she moved on.

She hadn’t looked back into whether the state had kept its promise of publishing data and creating its day care database until The 19th called her near the end of 2023.

Hawaii is now the state most behind in implementing the federal child care safety requirements.

The state told The 19th it is struggling to do so with a child care regulation department made up of only three people. The entire Human Services Department has a vacancy rate of about 25 percent.

Dayna Luka, the child care regulation program administrator in the Hawaii Department of Human Services, told The 19th that the state isn’t posting recent data because it has not finalized its definitions of serious injury and abuse. Without a definition, Hawaii can’t track the data, and it’s not posting it online. It’s the only state that doesn’t have its definitions finalized, The 19th’s analysis of the states’ child care plans found.

The process of creating definitions is long and requires public hearings and comments. The last time Hawaii had a public hearing for child care regulations was in 2021, Luka said.

“We may not be reporting that data because we don’t have the definition, but we are definitely investigating any kind of allegation of injury, any kind of violation of our licensing rules,” Luka said.

The state said it is asking the federal office for technical assistance to begin reporting serious injuries and abuse, but it didn’t provide a timeline for when it will begin doing so. It hopes to have its day care provider dashboard, as well as inspection reports, online by the summer. For now, it contracts with the state’s child care resource and referral agency for its child care provider database, but that dashboard doesn’t include inspection reports.

On a national level, it is impossible to know how many cases are not getting reported or investigated in child care because there is so much that falls into a gray area, said Christopher Greeley, a professor of pediatrics at the Baylor College of Medicine who has spent more than two decades studying pediatric abuse and neglect. And those investigations are further complicated because of their charged, emotional nature, leading to inaccurate recollections, as well as witnesses who may not be verbal.

“The narrower question of, ‘Is this injury abuse versus not?’ becomes quite fraught with difficulty because we all may agree the child has a broken bone, but now I’m adding a value judgment of whether that was done intentionally or not and some of that information may not be available,” Greeley said. That’s in part because some states don’t even have the capacity to thoroughly investigate those cases.

Advocates have been calling for more funding for the child care system, which could help states finally meet all of the safety requirements in CCDBG. A national effort to inject $400 billion over 10 years into child care failed in 2022, and other proposals haven’t found traction. It’s a hard truth in child care: A system that has been under-resourced for its entire existence can’t solve the big problems if it’s fighting to exist in the first place.

“One of the reasons that we talk about the need for a comprehensive system is that we understand then that the data would also be easier to track,” said Nina Perez, the early childhood national campaign director at MomsRising, a national network of moms pushing for child care and other family policies. “Any parent would tell you that they absolutely want reporting and transparency, particularly in instances of neglect and harm. This is a situation where the government needs to step up and resource that, including state governments.”

Anne Hedgepeth, the current chief of policy and advocacy at Child Care Aware, said states and child care providers “understand the seriousness or importance of the work they’re doing.” But “ultimately, licensing is complex and not every state system is sufficiently funded to do this work. Until we fix that problem, reporting won’t be as robust or transparent as it needs to be.”

When the country considers what another reauthorization of CCDBG might look like in the coming years, more support for compliance on health and safety could be areas marked for improvement, said Smith, who crafted the 2014 reauthorization. She wants to see the Government Accountability Office audit the states. And it could be a time to revisit whether the data needs to be reported at the federal level.

Through her own work, King understands the complexities of data collection. She worked at a state agency and knows what it means to be under-resourced, for things to take time. But she also carries the burden of being a parent who has lived through the death of a child that happened — at least in part, she feels — because the accountability wasn’t there.

A recent photo of Cynthia King and her family in Hawaii. (COURTESY OF CYNTHIA KING)

A recent photo of Cynthia King and her family in Hawaii. (COURTESY OF CYNTHIA KING)

A decade after her son’s death, she is still often struck by how many of the systems that are in place for other industries aren’t yet standard in child care. King, who this week marked the 10-year anniversary of her son’s death, said she was shocked to learn Hawaii was still so behind.

“I have been chronically disappointed in the level of response,” King said. “I understand that everybody is overtasked and under-resourced but I do think it’s such an important issue. It’s been devastating to not see progress made.”

Since Wiley died, King has had two more children, a boy and a girl — children she’s had to leave at the door of a provider after her trust was shattered.

“My husband and I are both lucky that we came out on the other side of Wiley’s passing away,” King said, but when it came time to decide where to put their children, they put their trust somewhere else.

They found a day care provider who they felt was taking all the safety precautions necessary, who was keeping the number of children they cared for low and who let the families into their space. A person who did everything possible to ensure they weren’t reported.

Ultimately, King turned away from the system that was built to ensure safety. The system that failed her.

Instead, she put her children in unlicensed care.

Cynthia King reads to her son Dexter Muir at their home in Honolulu, Hawaii, in 2016. (CORY LUM/CIVIL BEAT)

Cynthia King reads to her son Dexter Muir at their home in Honolulu, Hawaii, in 2016. (CORY LUM/CIVIL BEAT)

A recent photo of Cynthia King and her family in Hawaii. (COURTESY OF CYNTHIA KING)

A recent photo of Cynthia King and her family in Hawaii. (COURTESY OF CYNTHIA KING) (Chanelle Nibbelink)

(Chanelle Nibbelink) (Chanelle Nibbelink)

(Chanelle Nibbelink) (Chanelle Nibbelink)

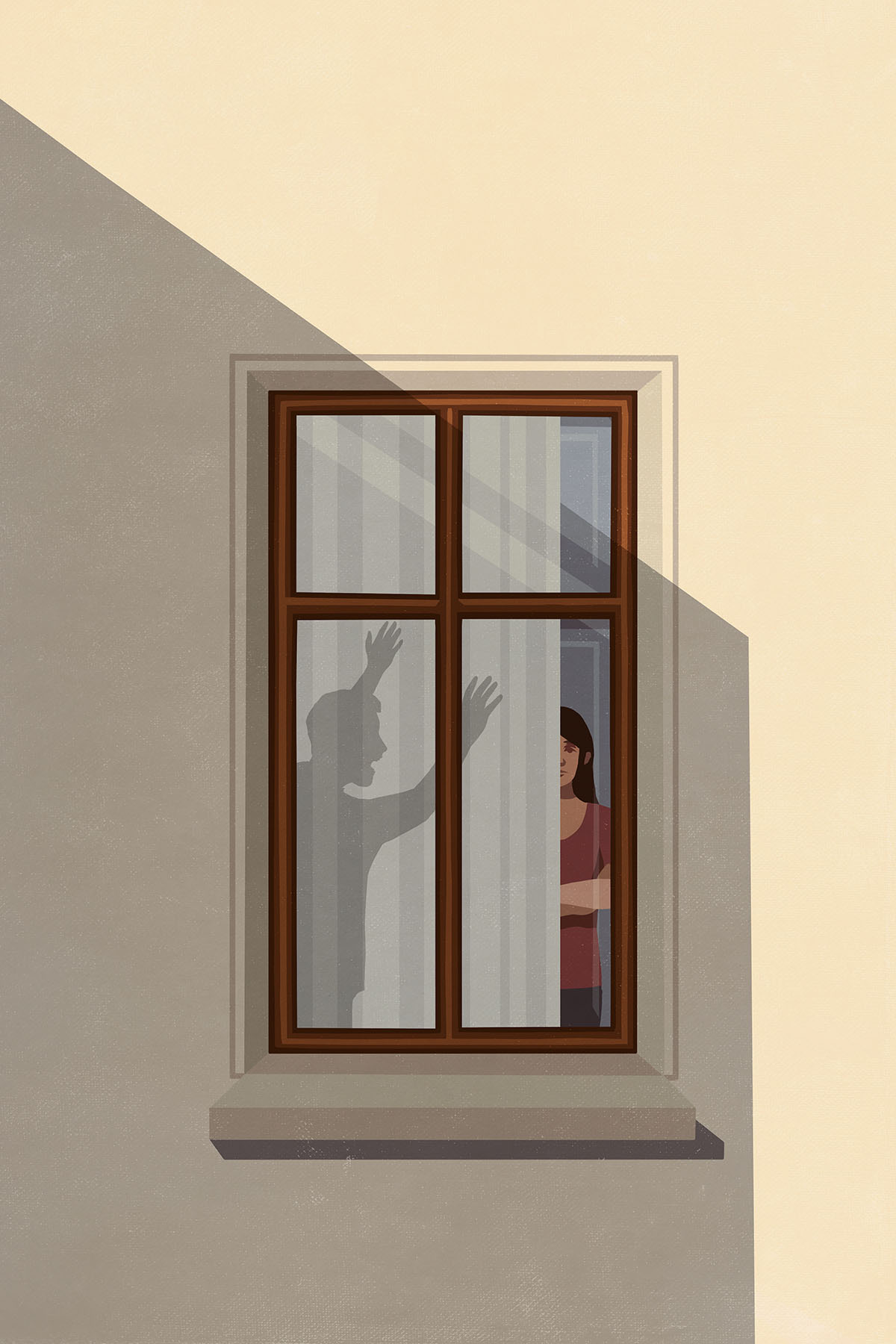

(Chanelle Nibbelink) Forty-one percent of all women and a quarter of men experience sexual or physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, according to 2022 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Getty Images)

Forty-one percent of all women and a quarter of men experience sexual or physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime, according to 2022 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Getty Images) Currently only six of the 13 states and D.C. that have paid family and medical leave laws include provisions for domestic violence survivors. (Getty Images)

Currently only six of the 13 states and D.C. that have paid family and medical leave laws include provisions for domestic violence survivors. (Getty Images) (Hermann Mueller/Getty Images)

(Hermann Mueller/Getty Images) Steve Ammidown poses for a portrait at his home in Bowling Green, Ohio. (Maddie McGarvey for The 19th)

Steve Ammidown poses for a portrait at his home in Bowling Green, Ohio. (Maddie McGarvey for The 19th) Steve Ammidown and his wife, Michelle Chronister, hold their daughter. (Maddie McGarvey for The 19th)

Steve Ammidown and his wife, Michelle Chronister, hold their daughter. (Maddie McGarvey for The 19th) John Kuehl and his kids in Madison, Wisconsin (Courtesy of John Kuehl)

John Kuehl and his kids in Madison, Wisconsin (Courtesy of John Kuehl)

Steve Ammidown and June hug before making dinner.

Steve Ammidown and June hug before making dinner.