‘It shouldn’t be the wild west’: Wisconsin lacks clear system to track police caught lying

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

An Appleton police detective pleaded guilty to forging official signatures on search warrants used in a drug investigation. He was fined $500, far short of the maximum penalty of $10,000 and 3 ½ years in prison.

During sentencing April 30 in Outagamie County Circuit Court, the judge noted that former Appleton Police Sgt. Jeremy Haney’s dishonesty “may impugn any number of cases on which he has been involved.”

But whether prosecutors in Outagamie County track dishonesty among law enforcement officers isn’t clear. Unlike the majority of counties that disclosed who committed what are known as Brady violations, Outagamie was among 17 offices that either denied a Wisconsin Watch records request or said it didn’t keep track. Prosecutors must tell defense attorneys about such violations whenever those officers are called upon to testify in a criminal case.

ALSO READ: How Trump could run for president from jail

A Wisconsin Watch investigation seeking Brady files from all 72 counties found more than 360 examples in 31 counties of current and former Wisconsin law enforcement officers who prosecutors have flagged for dishonesty or breaking the law in ways that could undermine their credibility in court.

That’s a small fraction of the state’s 15,000 sworn law enforcement officers. But it’s also an incomplete number because of the inconsistency among district attorneys in tracking the information.

The lists include a Vernon County police chief who instructed a subordinate who fell asleep at the wheel and crashed his squad car to say he swerved to miss a dog. Prosecutors in two counties have said they won’t charge cases involving the still sitting Ontario police chief due to his history of dishonesty.

Also included was a Fond du Lac detective who was investigated by state agents and ultimately pushed out of the department following a pattern of sending demeaning text messages, racially profiling innocent people, mishandling evidence and attempting a cover-up. Criminal charges were never brought, but the DA declared the detective’s “credibility will be attacked in any testimony he is asked to provide and may present significant hurdles.”

Another 23 district attorneys said they had no names on file, though some said in response to Wisconsin Watch’s inquiry that they would reach out to local agencies to update their list.

Milwaukee County released a list of 150 former officers who had been prosecuted and in all but two cases convicted of crimes over the past 20 years. But it withheld its list of officers who had been investigated for dishonesty and other issues but never charged with a crime, citing case law that exempts prosecutorial files from public disclosure.

Jim Palmer, executive director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association (Submitted photo)

Jim Palmer, executive director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association (Submitted photo)

The lack of legal clarity has vexed defense lawyers and law enforcement officers — natural adversaries in the criminal justice system — who both say the current system can be confusing to navigate.

“It shouldn't be the wild west,” said Jim Palmer, executive director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association, the largest police union in the state. “Some DAs may keep a list, some may not. … And whatever the procedure that a DA currently in office may utilize doesn't mean that any of their successors are going to do it the same way.”

Defense attorneys say efforts to obtain information about past lying by police officers are in some instances stymied by lax record keeping or resistance to sharing information, although not in all cases.

“We may have a unified court system, but we really are 72 different criminal legal systems,” said Adam Plotkin, legislative liaison in the State Public Defender’s Office. “How it's handled county by county can vary pretty dramatically.”

Prosecutors have a constitutional duty to turn over exculpatory evidence — including evidence of anything that calls into question an officer’s honesty — but there’s little oversight to ensure that always happens.

So far only one state, Colorado, has attempted to create a uniform system, though law enforcement lobbyists have been working behind the scenes to change Wisconsin law to make it easier for police to be removed from Brady lists.

Varying methods and levels of transparency

Named for the landmark 1963 U.S. Supreme Court decision Brady v. Maryland, the Brady doctrine began in what became a series of federal and state precedents requiring the government to disclose exculpatory evidence — material that could be favorable to the defense — even if it might weaken the prosecution’s case. Over the years, courts have expanded that principle to include any evidence that could impeach the credibility of the prosecution’s witnesses — including police officers — who were involved and helped build the case.

Ozaukee County District Attorney Adam Gerol (Submitted photo)

Ozaukee County District Attorney Adam Gerol (Submitted photo)

A Wisconsin Watch analysis found the way district attorneys collect and manage Brady information — if that happens at all — is up to individual officeholders, and the methods and transparency vary. Only Iron County didn’t respond months after the initial request and despite multiple follow-up requests.

"I suspect you’re going to run into different practices depending on the size of the county,” wrote Ozaukee County District Attorney Adam Gerol.

Gerol provided his most recent example of disclosure — a 2020 letter to a criminal defendant outlining three instances of apparent dishonesty involving a former police sergeant involved in the case who had apparently lied about legal advice he received from the DA’s office.

There are no active officers in Ozaukee County subject to Brady disclosure, so there isn’t a current list, Gerol said. He relies on agencies to disclose if an officer giving testimony has ever been dishonest, but he has “never had a need to periodically request this information because I’m the one either discovering it or learning about it from the police in real time.”

In Green County, District Attorney Craig Nolen regularly sends out a three-page memo to law enforcement detailing the legal importance of full disclosure.

Green County DA Craig Nolen (Submitted photo)

Green County DA Craig Nolen (Submitted photo)

“We understand that disclosure of findings of dishonesty may have significant consequences as to the effectiveness of officers and employees in their chosen careers,” Nolen wrote in a letter to law enforcement in 2023. “However, I am sure that such a finding in a disciplinary proceeding was not made lightly nor without due process. It is neither fair nor reasonable to expect prosecutors to risk their law licenses to hide another employee’s intentional negative conduct.”

Nevertheless, Nolen refused to publicly release the names of the officers he has on file, citing case law that often places a prosecutor’s files beyond the reach of open records requests.

In Waukesha County, District Attorney Sue Opper initially denied Wisconsin Watch’s records request for a Brady list saying “no records exist.” But upon follow-up she admitted the office does have Brady letters for several individual officers on file and produced 11 letters after deadline and shortly before publication of this story.

The lack of consistency and transparency on Brady information has long frustrated watchdog groups seeking to hold police agencies accountable for officer misconduct. Defense attorneys are also wary of prosecutors leaving it up to law enforcement agencies to self-report.

“Some prosecutors are more diligent about tracking it than others,” Plotkin said.

‘You can’t fart without somebody catching it’

The circumstances that could land an officer on a list vary, but all come down to an incident involving dishonesty.

For example, in 2019 Village of Ontario Police Chief David Rynes advised a part-time officer who had crashed his patrol car to make up a story about swerving to miss a dog after he fell asleep at the wheel in a neighboring county. Monroe County sheriff’s deputies recommended criminal charges against both the officer — who is no longer in law enforcement — and the police chief for their dishonesty, though neither ultimately was charged.

Rynes continues in his role even though he’s on Brady lists in multiple counties. Monroe and Vernon county prosecutors maintain they won’t bring cases to court that would rely on Rynes’ testimony.

Monroe County District Attorney Kevin Croninger told Wisconsin Watch his office doesn’t maintain a formal Brady list. His office enters names in a statewide database called Protect used by prosecutors across jurisdictions at their own discretion.

Prosecutors in other sparsely populated counties described a more informal approach to flagging dishonest officers but insisted they take oversight seriously in communities where people know each other.

“In Buffalo County you can't fart without somebody catching it,” District Attorney Tom Bilski said.

He said in years past he witnessed instances of flagrant dishonesty among law enforcement that prompted jurors to acquit defendants.

“There were sheriff's deputies that perjured themselves on the stand on a regular basis,” Bilski said. “None of those officers are still around.”

He said the roughly 20 officers in his county are part of a new generation of police who he believes are more ethical. He said he and his assistant read every police report that accompanies a criminal complaint looking for inconsistencies or evidence of dishonesty.

“If I have any inclination that an officer's gonna perjure themselves on the stand, I will immediately put them on a list, and they'll know that and I'll dismiss the case,” he said.

“It's a big issue for me,” he added. “I just don't have anybody to put on the list.”

So-called “wandering officers” — police who are fired or forced to resign over misconduct and then land jobs with other agencies — may be on one county’s list but not another depending on the level of record keeping.

Only decertified officers are prevented from being rehired. Recently the investigative nonprofit The Badger Project uncovered evidence of more than 300 examples of wandering officers in Wisconsin, a trend it found has increased over the past three years.

Walworth County District Attorney Zeke Wiedenfeld told Wisconsin Watch his office relies on a traditional paper file with letters for about 20 current and former officers who have documented instances of dishonesty.

“We don't compile a list,” he said in an interview.

His approach is to release any names he receives from law enforcement to defense attorneys and then leave it up to them to request records from the police department.

One officer in his file is Patrol Officer Casey Apker, who was suspended multiple times and ultimately fired from the Kenosha Police Department in 2014 over allegations he harassed a female colleague, aggressively confronted a citizen over an off-duty parking dispute and responded to calls outside of his assignment area.

Apker, who has worked as a police officer since 2021 in the village of Sharon in Walworth County, is among 15 former and current officers included on a Brady list provided by the Kenosha County DA.

Casey Apker was fired from the Kenosha Police Department in 2014 but later hired in Walworth County. The district attorneys in Kenosha and Walworth counties keep track of his name to comply with what are known as Brady disclosure requirements, but had different responses to requests for those records.

Casey Apker was fired from the Kenosha Police Department in 2014 but later hired in Walworth County. The district attorneys in Kenosha and Walworth counties keep track of his name to comply with what are known as Brady disclosure requirements, but had different responses to requests for those records.

“He was fired in front of the public,” Kenosha Police Department spokesperson Lt. Joshua Hecker said. “If any police department ever did a background check, they should be able to find that fairly easily.”

He was nevertheless hired in Walworth County in 2016 but resigned in lieu of termination from the Town of Geneva department less than a year later for dishonesty. He worked for nearly two years for the Town of Burlington Police Department in Racine County and then was hired by the Village of Sharon Police Department, where he has worked full-time since 2021.

“He’s been a good officer for us — great work,” Sharon Police Chief Brad Buchholz told Wisconsin Watch.

Wiedenfeld knew Apker’s name from the 20 or so current and past officers he keeps in his paper file.

“I agree everybody does it a little bit different,” Wiedenfeld said.

Longtime Kenosha County District Attorney Mike Graveley said the old practice was not to keep a list but rather a voluminous paper file for any documented dishonesty self-reported by police officers who were asked to complete a questionnaire.

“We did no analysis,” Graveley said. “We just simply collated that information and collected it. And then if somebody sent us an open records request, we sent out all of the names.”

But several months ago his office began scrutinizing each name and making its own call on whether missteps should rise to the level of disclosure to defense counsel.

“Any individual that we felt did not meet the standard of something we would need to disclose to defense counsel as exculpatory evidence,” Graveley said, “that person is no longer included in any list.”

Other district attorneys either didn’t track dishonest officers or were unwilling to share names with the public.

Outagamie, Waupaca, Door, Manitowoc, Pierce, Polk and Rusk counties all rejected the records request with responses that used the exact same wording.

Polk County District Attorney Jeffrey Kemp said he worried about unspecified harm from releasing his office’s Brady list to the media.

“My concern is that such information will potentially be abused by entities that may have an agenda that is, perhaps, not foreseen by your organization,” he wrote in response to Wisconsin Watch’s records request.

Rusk County District Attorney Ellen Anderson, who was appointed by Gov. Tony Evers in 2022, reversed her initial denial after being contacted by Wisconsin Watch and affirmed her office has no current Brady listed officers or policies or procedures in place.

Some jurisdictions more diligent than others

The Dane County district attorney in Madison released a list with 25 names on it from 10 law enforcement agencies with the caveat that not all officers may still be employed by that department.

The state Department of Justice has resisted sharing its list of currently active law enforcement officers, making it difficult to cross-reference names.

Likewise, Winnebago County District Attorney Eric Sparr released a list with the names of 29 officers from the Wisconsin State Patrol, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh and Appleton Police Department in neighboring Outagamie County. Some names were listed more than 20 years ago, and it’s unclear how many still work in law enforcement.

The Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office — which oversees more than a fifth of all sworn officers in the state — released a list with 150 names going back 20 years listing criminal charges against the officers.

However, the county declined to release “records relating to individuals on the list who were referred for prosecution but not charged,” wrote Milwaukee County Deputy District Attorney Karen Loebel.

In many cases officers on Brady lists due to dishonesty were never accused of a crime. The standard set by the nation’s highest court sets a record of untruthfulness that can include giving conflicting testimony under oath or lying in the course of an administrative investigation.

That’s how former Sheboygan Police Officer Bryan Pray ended up on a Brady list in 2023. After being caught distributing nude photos of a female colleague, he “gave false information or was not completely forthcoming to investigators in interviews where he was required to tell the truth,” investigators wrote.

Charges were never filed, and he resigned only after Wisconsin Watch and the Sheboygan Press reported details of his misconduct.

In Brown County, prosecutors in Green Bay released a list with 16 names but with no context on why they were included or whether they were still employed.

“For more specific information about each, I would refer you to the respective agency where the officer is or was employed,” Brown County District Attorney David Lasee wrote.

The list included no dates or corresponding agencies.

Colorado law creates statewide standard

Legal experts say Wisconsin’s example of uneven transparency standards is common nationwide.

“It's completely and sadly normal,” said Rachel Moran, an associate law professor at University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis, who has criticized systemic failures to enforce Brady rules.

Only Colorado has a law requiring the maintenance of Brady lists and explaining what those lists should look like, she noted.

The law established a six-member oversight committee that includes a majority appointed by police groups and prosecutors who are empowered to decertify officers for “untruthfulness.” It also mandated that officers flagged for dishonesty be tracked in the public-facing database.

Colorado’s system also enshrines a notification requirement for officers before they’re placed on a list and lays out a process for them to petition removal.

A mechanism that would allow officers to challenge and be removed from a Brady list has been a priority for Wisconsin law enforcement groups, which records show have been quietly lobbying on the issue since last July.

“It's just a conversation that we've been having with the state Legislature,” Badger State Sheriffs’ Association President and Dodge County Sheriff Dale Schmidt said, adding it’s something they’ll be discussing again next session.

“I have come across incidents where individuals have been wrongly accused of things,” he said. “They never had the opportunity to have that due process to at least share both sides of the story.”

Badger State Sheriffs’ Association President Dale Schmidt answers questions at a press conference in July 2016 in Dodge County, Wis. (Mike Sears / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Badger State Sheriffs’ Association President Dale Schmidt answers questions at a press conference in July 2016 in Dodge County, Wis. (Mike Sears / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Hecker, the Kenosha Police spokesperson, recounted how he had lied to his captain in 2006 about pursuing a suspect as a cover story for allowing a trainee to get a squad car stuck in the mud.

He was written up for dishonesty and placed in the DA’s Brady file, which prompted extra scrutiny from prosecutors whenever he would be called to testify.

“This was an isolated incident that happened out of fear, and it was stupid, and I readily and immediately admitted my wrongdoing,” Hecker told Wisconsin Watch. “And then for the next 20 years in my career it labeled me — which isn't fair.”

The incident didn’t hinder either of the officers’ careers.

“The guy that I was training is our chief of police and I'm in internal affairs,” Hecker added.

Defense attorneys are skeptical of how an officer flagged for dishonesty could later be delisted without running afoul of the constitutional principle that a person’s past dishonesty should be disclosed.

“The mere passage of time doesn't change the fact that it's still exculpatory,” said Dean Strang, a veteran Madison defense attorney who also teaches at Loyola University Chicago School of Law.

If it was indeed a minor thing or there’s evidence it was blown out of proportion, the prosecutor always has the ability to argue that it’s admissible, and if the judge agrees the defense can raise it in court.

“Whether it comes in at trial is an entirely different question,” he added.

Wisconsin Watch inquiry sparks conversations

District attorney vacancies are filled by governor’s appointees who report being tasked with running prosecutions with little formal guidance. Evers’ office referred questions to DOJ.

DOJ officials didn’t respond to a request for comment. The agency said it doesn’t have a statewide Brady list.

The Wisconsin Office of Open Government released materials prepared by local district attorneys that cover Brady doctrine that were apparently used to train prosecutors in other counties. The only policy document was a decade-old memo reminding prosecutors in the state attorney general’s office of their responsibilities.

“Prosecutors have a duty to make reasonable efforts to obtain exculpatory information from law enforcement agencies,” the four-page memo from 2013 states.

But Wisconsin Watch could not find any evidence of uniform guidance to local prosecutors. In one 2014 document the agency acknowledged offices in different-sized counties will handle it differently.

Several district attorneys told Wisconsin Watch they were unaware of the existence of state guidance. Some reported they only reached out to law enforcement agencies for a list of dishonest officers after Wisconsin Watch asked for their list.

‘There’s integrity in enforcing some integrity’

Palmer, the police union head, said the Colorado model is better than Wisconsin’s nonexistent standard. Law enforcement wouldn’t necessarily object to having the lists be made public, he added.

“The public does absolutely have the right to know what officers are on Brady lists, but they also ought to have some confidence that those determinations are made appropriately,” he said.

Adam Plotkin, legislative liaison to the Wisconsin State Public Defender’s Office (Submitted photo)

Adam Plotkin, legislative liaison to the Wisconsin State Public Defender’s Office (Submitted photo)

The Public Defender’s Office would like to see a consistent standard but Plotkin, its legislative liaison, said it would need to see the proposal.

“Uniformity is helpful if it lands on the side of providing the information, making it available,” Plotkin said. “Uniformity would not be helpful if it essentially provides a shield from accessing that information.”

He also criticized Colorado’s model for having a six-person oversight committee composed of police and prosecutor appointees who ultimately decide whether a police officer’s past misconduct would be made public.

“The council that governs how this all works is headed by the people that it's intended to track,” he added. “So you want to make sure that there's integrity in enforcing some integrity.”

The lack of statewide standards or oversight from DOJ leaves prosecutors to make judgment calls that have life-changing ramifications based on one person’s word against another.

“Law enforcement officers get an enhanced presumption of credibility — it's just the way of the world,” Plotkin said. “And so when you have that heightened presumption of credibility, there should be heightened scrutiny.”

Editor's note: This story was updated after publication with a response from Waukesha County. It also updates a quote from Ozaukee County District Attorney Adam Gerol that was missing a contextual part of his statement.

Tyler Barth, a Hortonville cement contractor, says Outagamie County Judge Mark McGinnis jailed him over a financial dispute with a disgruntled client who worked in the courthouse. He is seen on Sept. 8, 2023, at a job site in Appleton, Wis. (Jacob Resneck / Wisconsin Watch)

Tyler Barth, a Hortonville cement contractor, says Outagamie County Judge Mark McGinnis jailed him over a financial dispute with a disgruntled client who worked in the courthouse. He is seen on Sept. 8, 2023, at a job site in Appleton, Wis. (Jacob Resneck / Wisconsin Watch) Judge Mark McGinnis was elected at the age of 34 in 2005 but hasn’t faced an electoral opponent since. He is seen on Dec. 13, 2022, in Outagamie County Circuit Court in Appleton, Wis. (William Glasheen / USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

Judge Mark McGinnis was elected at the age of 34 in 2005 but hasn’t faced an electoral opponent since. He is seen on Dec. 13, 2022, in Outagamie County Circuit Court in Appleton, Wis. (William Glasheen / USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin) John Gross is director of the University of Wisconsin Law School’s Public Defender Project. He reviewed court transcripts in Tyler Barth’s criminal case and said there’s an appearance that the judge exceeded his legal authority by jailing him over an unrelated civil dispute. (Courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison)

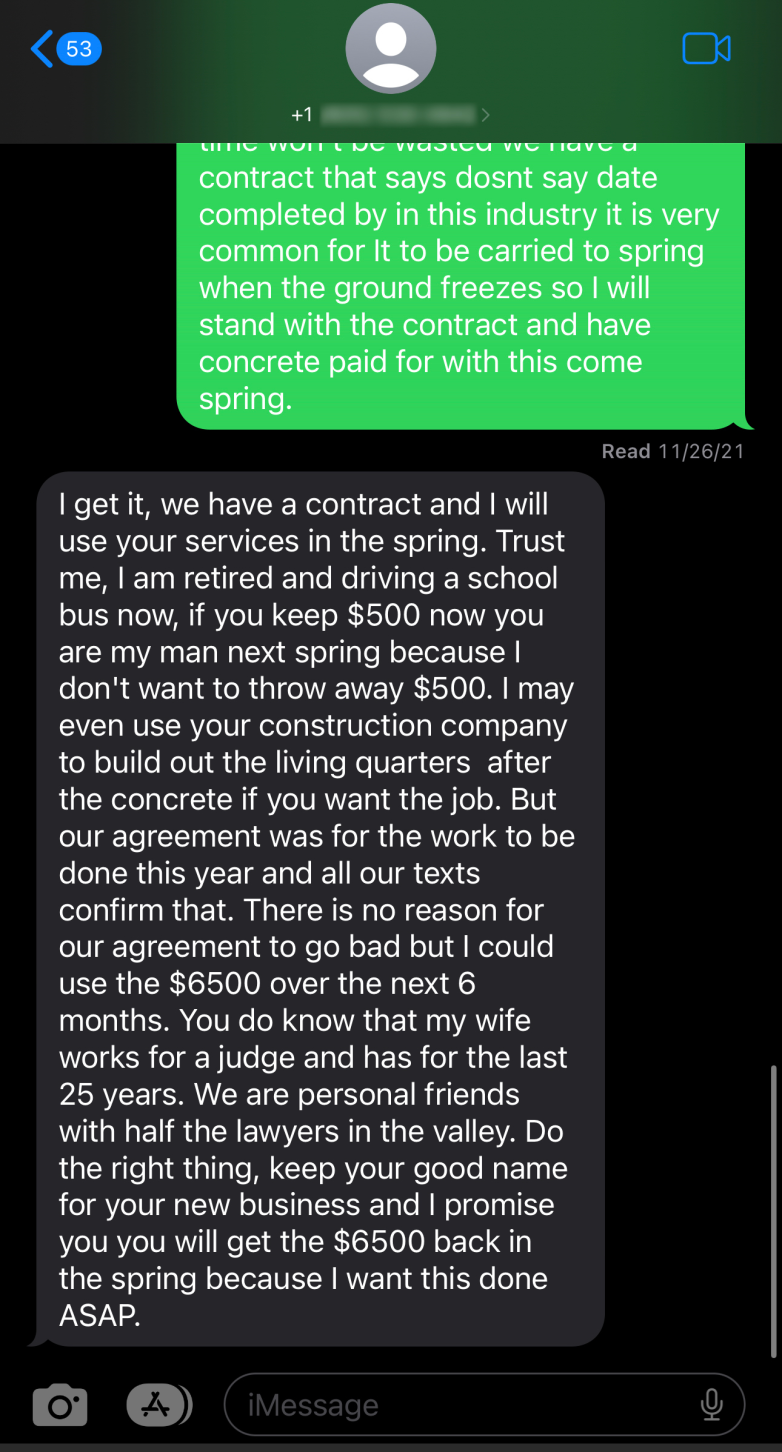

John Gross is director of the University of Wisconsin Law School’s Public Defender Project. He reviewed court transcripts in Tyler Barth’s criminal case and said there’s an appearance that the judge exceeded his legal authority by jailing him over an unrelated civil dispute. (Courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison) A Text message from Wayne Dorsey to Tyler Barth on Nov. 16, 2021, in which he warns the Hortonville cement contractor that his wife — a courthouse employee — had ties to the legal community and there could be consequences if they didn’t come to terms.

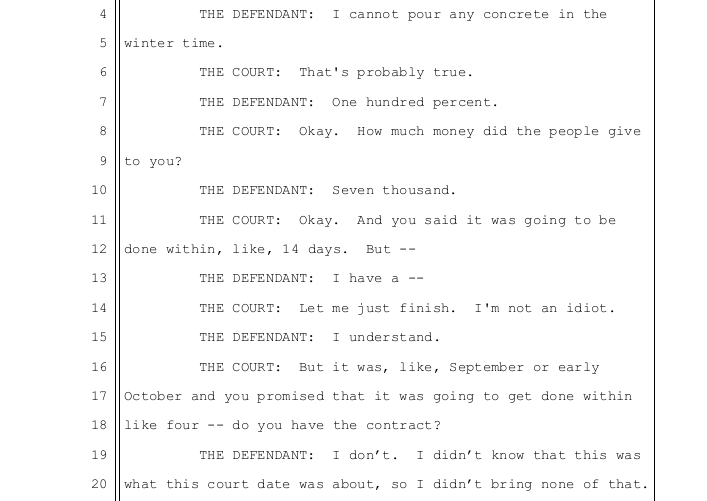

A Text message from Wayne Dorsey to Tyler Barth on Nov. 16, 2021, in which he warns the Hortonville cement contractor that his wife — a courthouse employee — had ties to the legal community and there could be consequences if they didn’t come to terms.  A Dec. 20, 2021, Court transcript shows Outagamie County Judge Mark McGinnis questioning Tyler Barth about a cement contract dispute with a courthouse employee during a criminal probation hearing. It’s unclear from public records how McGinnis knew about the unrelated financial dispute.

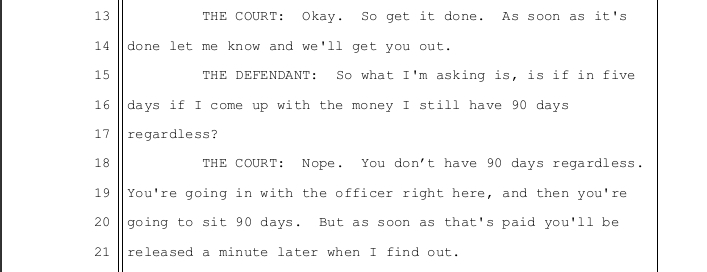

A Dec. 20, 2021, Court transcript shows Outagamie County Judge Mark McGinnis questioning Tyler Barth about a cement contract dispute with a courthouse employee during a criminal probation hearing. It’s unclear from public records how McGinnis knew about the unrelated financial dispute. A court Transcript from Dec. 20, 2021, shows the moment when Outagamie County Judge Mark McGinnis jailed Tyler Barth over a $7,000 contract dispute in an unrelated criminal probation hearing.

A court Transcript from Dec. 20, 2021, shows the moment when Outagamie County Judge Mark McGinnis jailed Tyler Barth over a $7,000 contract dispute in an unrelated criminal probation hearing. A Portrait of a former police recruit taken near her home outside of Wisconsin on Sept. 17, 2023. The woman says she doesn’t think the Grand Chute Police Department should have investigated her sexual assault allegations against two law enforcement academy classmates. (Jenn Ackerman for Wisconsin Watch)

A Portrait of a former police recruit taken near her home outside of Wisconsin on Sept. 17, 2023. The woman says she doesn’t think the Grand Chute Police Department should have investigated her sexual assault allegations against two law enforcement academy classmates. (Jenn Ackerman for Wisconsin Watch) A Portrait of a former police recruit taken near her home outside of Wisconsin on Sept. 17, 2023. Her former agency recommended no charges after concluding a sexual assault investigation within 34 hours, which one criminal justice expert calls “troubling.” (Jenn Ackerman for Wisconsin Watch)

A Portrait of a former police recruit taken near her home outside of Wisconsin on Sept. 17, 2023. Her former agency recommended no charges after concluding a sexual assault investigation within 34 hours, which one criminal justice expert calls “troubling.” (Jenn Ackerman for Wisconsin Watch) A Portrait of a former police recruit taken near her home outside of Wisconsin on Sept. 17, 2023. The two men she accused of sexual assault are no longer in law enforcement, but could be eligible to reapply to a law enforcement academy as early as next year. (Jenn Ackerman for Wisconsin Watch)

A Portrait of a former police recruit taken near her home outside of Wisconsin on Sept. 17, 2023. The two men she accused of sexual assault are no longer in law enforcement, but could be eligible to reapply to a law enforcement academy as early as next year. (Jenn Ackerman for Wisconsin Watch)