Railroaded: In the wake of the East Palestine disaster, other train towns wonder if they're next

This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist's weekly newsletter here.

A low, bellowing train horn haunts the daily routine of Camanche, Iowa. It’s there in the morning when diners shuffle into Spring Garden Family Restaurant, the only place open for breakfast. They sit at a two-top counter while local news plays on a muted television and pounds of soon-to-be crispy hash browns kiss the griddle.

In the afternoon, Alice Srp sits in her dining room and looks at the Mississippi River. She is talking about the train derailment that happened earlier this year in East Palestine, Ohio, when the horn blares again, stopping the conversation.

“That situation in Ohio was so sad,” Srp said. “You feel for those people, but your heart is thinking, ‘Are we going to be [next]?’”

Alice Srp sits on the porch of her home in Camanche, Iowa. She said trains have become increasingly filled with hazardous oil and chemicals, and she worries about future disasters along the Mississippi River. Grist / John McCracken

A large sign welcomes visitors to Camanche, Iowa. The town, located on the banks of the Mississippi River, is one of the many railroad communities increasingly worried about potential train disasters involving toxic chemicals. Grist / John McCracken

A large sign welcomes visitors to Camanche, Iowa. The town, located on the banks of the Mississippi River, is one of the many railroad communities increasingly worried about potential train disasters involving toxic chemicals. Grist / John McCracken

Later that evening, the horn cuts through the noise at the Poor House Tap at the edge of town. As the train roars by, its resonance is dulled a bit by the chatter of patrons and the barks of Zoe, a labradoodle who knows there are treats behind the bar. She is unmoved as the sound cuts through town, grabbing the attention of locals.

Camanche, located on the banks of the Mississippi River three hours east of Des Moines, is no stranger to the sound of trains. But for some people in this town of 4,500, the familiar sounds of a train whistle now bring an unfamiliar reaction: fear.

A train with at least eight oil tankers moves through Camanche, Iowa, at 9 o’clock at night. Grist / John McCracken

A train with at least eight oil tankers moves through Camanche, Iowa, at 9 o’clock at night. Grist / John McCracken

After a train derailed in East Palestine in February — resulting in a towering black plume of smoke, the burning of toxic chemicals, and the evacuation of the town — health concerns still linger, and cleanup woes have plagued the rural community.

In the months since, residents in railroad communities across the country have become increasingly worried about the potential disaster aboard trains. Camanche has become a hotbed of concern over an international railroad merger projected to triple the number of trains moving through town.

Canadian Pacific Railroad, a major rail company headquartered in the province of Alberta, officially purchased Kansas City Southern Railroad in April. The merger, estimated to cost Canada Pacific $31 billion, is the first merger of major railroad companies in two decades.

With this new merger comes a first-of-its-kind rail line connecting Canada, the United States, and Mexico. This route will also directly link Canadian tar sands oil to Gulf Coast refineries, with increased traffic along the way.

Crude oil could be shipped from Canada to Texas and Mexico, refined into petrochemicals on the Gulf Coast, then shipped across the country to its destination.

Camanche currently sees around eight trains a day. After the merger traffic picks up, the city is expected to see upward of 21 trains a day. Other cities along the merger route will see a similar increase, raising the odds of another disaster like the one that struck East Palestine. What separates Camanche is the unique way that railroad tracks isolate residents, creating particularly frightening possibilities for the town.

Standing in Kitt Swanson’s driveway, the first thing you notice is how close the home is to the tracks. She said the trains don’t seem to bother Kiyiyah, her docile Alaskan malamute, but the rails are a few feet from her backyard and shake the house each time a train passes.

Kitt Swanson’s Alaskan malamute, Kiyiyah, rests on the floor of Swanson’s garage in Camanche, Iowa. Grist / John McCracken

Kitt Swanson’s Alaskan malamute, Kiyiyah, rests on the floor of Swanson’s garage in Camanche, Iowa. Grist / John McCracken

Swanson, who has lived in the home for three years, said she worries she and the roughly 1,000 people on the river side of the tracks are without help when trains pass through. When a train comes through town, the only way out for her and others on this side of the tracks is by boat.

“I’m a brittle Type 1 diabetic,” Swanson said. “If I need EMS care, how am I going to get it when all the tracks are blocked?”

Here lies the problem with the expected increase in rail traffic. When a train comes through Camanche, all seven of the crossings are blocked at the same time. This creates a steel wall, isolating more than 1,000 residents from the rest of the town. The only way out is by boat or to wait for the train to pass.

A red line highlights the railroad tracks running through Camanche, Iowa, as seen in an aerial view. In the event of a long train derailment, residents worry that the section of town between the Mississippi River and the train could be isolated from emergency services. Homes to the right of the red line aren’t accessible by road when trains roll through town. Google Earth

A red line highlights the railroad tracks running through Camanche, Iowa, as seen in an aerial view. In the event of a long train derailment, residents worry that the section of town between the Mississippi River and the train could be isolated from emergency services. Homes to the right of the red line aren’t accessible by road when trains roll through town. Google Earth

The merger, combined with the fact that freight companies have increased the length of their trains in recent years, means that these residents may be in more danger than ever of being cut off from help, should disaster strike.

According to a report from the Government Accountability Office, train lengths have increased 25 percent from 2008 to 2019, with trains averaging at least 1.4 miles long. The same report found that some rail companies operate three-mile-long trains every week.

“Our biggest concern is simply that we don’t want people to be isolated from emergency services,” said Dave Schutte, the fire chief of Camanche.

Dave Schutte, the fire chief of Camanche, Iowa, drives through the town. His biggest concern with the approved rail merger is delayed emergency service response and potential derailments. Grist / John McCracken

Dave Schutte, the fire chief of Camanche, Iowa, drives through the town. His biggest concern with the approved rail merger is delayed emergency service response and potential derailments. Grist / John McCracken

Emergency services are in a bind when trains come through town. Schutte said he’s seen the trains block the tracks for over 10 minutes, which, under the right circumstances, could be life or death for some.

He said the city voiced its concerns to both the rail companies and the Surface Transportation Board, or STB, the federal agency in charge of regulation of rail and other modes of transportation. He said it was a long shot going into the discussions that something would change given the power that the rail businesses have.

“They only looked at super busy crossings in big cities where they have high traffic,” Schutte said. “To me, [being a small town] doesn’t devalue the importance of having those crossings open when they need emergency services.”

Now that the merger has been approved, Schutte said he’s focused on emergency preparedness in case of future derailments or blocked crossings. Right now, the city is developing a plan to evacuate residents via boat if a derailment blocks access to residents during an emergency.

A rail yard located just outside of Camanche is seen from above. This yard, which runs parallel to the Mississippi River, services nearby industrial facilities, such as chemical and ethanol production plants. Grist / John McCracken

A rail yard located just outside of Camanche is seen from above. This yard, which runs parallel to the Mississippi River, services nearby industrial facilities, such as chemical and ethanol production plants. Grist / John McCracken

This method has been internally described as the Dunkirk Method, a reference to the World War II evacuation of more than 300,000 British and French soldiers by boat.

In addition to potential emergency response delays, Schutte is also worried about the risks of what’s being carried on the trains, given the disaster in Ohio earlier this year.

“Just seeing what could happen to the community, and the devastation of just how bad it really could be depending on what chemicals are on the train, certainly elevates that concern even more,” Schutte said.

Ashley Foley, a mother of three who works from home, said the regular movement of chemicals and oil on rails is a concern that keeps her up at night, worrying about the safety of her family.

Two of Ashely Foley’s children stand in their front yard in Camanche, Iowa. Parents like Foley worry that trains carrying chemicals and oil could put their families’ lives at risk. Grist / John McCracken

Two of Ashely Foley’s children stand in their front yard in Camanche, Iowa. Parents like Foley worry that trains carrying chemicals and oil could put their families’ lives at risk. Grist / John McCracken

“If a train is going slow and it derails, it’s still scary, but the likelihood of us surviving would be higher,” Foley said. “Now with the stuff that they’re carrying, with trains going faster and being longer, I lay in bed at night and I wonder if tonight’s gonna be the night that it comes off the tracks and wipes out the backside of the house.”

While visiting Camanche, Grist observed a train car with at least eight oil tankers moving through the town after 9 p.m.

Before 38 train cars derailed in Ohio earlier this year, vinyl chloride was a little-known chemical. Now, national media attention has raised awareness of what’s being carried on the trains that move through the nation’s rural backyards.

Railroad tracks run right beside several homes in Camanche, Iowa. Kitt Swanson’s home is located at the closest left. Grist / John McCracken

Railroad tracks run right beside several homes in Camanche, Iowa. Kitt Swanson’s home is located at the closest left. Grist / John McCracken

According to the Federal Railroad Administration, or FRA, and the Association of American Railroads, there are more than 140,000 miles of railway in the U.S., the majority of which are in rural regions.

Oil is transported predominantly by pipeline. But oil capacity in pipelines is dwindling, with rail emerging as a popular means of moving crude oil. Between 2010 and 2014, oil by rail topped almost 1 million barrels a day, which represented 10 percent of American crude oil at the time.

At the time, questions over the safety of transporting oil by rail were in the spotlight after a disaster in Canada. In the early hours of July 6, 2013, an oil train jumped the tracks in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, and derailed, killing 47 people and leveling the area’s downtown, which has yet to recover.

Now that Canadian shale oil will have a direct path through the United States, concerns over oil explosions caused by train derailments have been rekindled. And though global oil demand is poised to slow, fossil fuel companies are pivoting to a similarly toxic industry.

Petrochemicals are manufactured from fossil fuels and used in a variety of industries, from plastics to fertilizers. In the past decade, fossil fuel companies have raced to build out their plastics divisions, refining oil into petrochemicals along the Gulf Coast and polluting the predominantly Black communities around them.

Global plastic production is estimated to quadruple by 2050, and with it, the risk of transporting volatile chemicals. Vinyl chloride, the now-infamous chemical that escaped from toppled train cars in East Palestine, is a petrochemical and known carcinogen.

The rail industry knows this, and train executives are betting on the continued growth of the petrochemical and plastics markets.

Speaking at an investors’ earnings call in October 2022, Canadian Pacific Executive Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer John Brooks said the rail company is starting to see petrochemicals shipped out of the Heartland Petrochemical Complex in Alberta, Canada. This newly built petrochemical facility is owned by Canadian energy company Inter Pipeline. Canadian Pacific is the only rail company it uses.

“Our partnership with Inter Pipeline expands Canadian Pacific’s plastic service to both export and domestic markets, and this volume growth will be a tailwind for us,” Brooks said.

When asked to comment, Canadian Pacific referred Grist to its STB merger application.

While oil and rail are betting on the petrochemical markets, environmental groups are working to prevent their expansion.

“We just don’t need it,” said Eric de Place, former director of the advocacy organization Beyond Petrochemicals. “They want to triple global plastics consumption, and we already have too much plastic.”

De Place said the pollution and public health dangers seen in East Palestine, Ohio, happen almost every day for communities around the country that reside near petrochemical facilities, just without the spectacle of a massive smoke cloud.

“The derailment in Ohio was horrifying, but in some way, it’s just a moving version of what happens in stationary locations all the time,” he said.

Heading west on Iowa Route 30 to Camanche, the Mississippi River is only visible through split-second cracks in the industrial corridor walling off the nation’s second-longest river.

Along the way, a massive corn mill owned by Chicago-based Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, or ADM, stretches for miles along the river. ADM is a leader in agriculture and food processing, making a variety of products, including corn oils, enzymes, and ethanol.

On an early Saturday morning in mid-May, roughly 80 oil tanker cars could be seen sitting along the tracks at the ADM facility. Their destination, and contents, were unknown. (ADM did not respond to a request for comment.) Some of these cars included rail placards that notate that hazardous materials are onboard, a practice created by the U.S. Department of Transportation and used to determine risk in emergency response situations.

A long train carrying several oil tankers moves next to a road in Bensenville, Illinois. The city is just one of the Chicago suburbs opposed to the recent Candian Pacific merger. Grist / John McCracken

A long train carrying several oil tankers moves next to a road in Bensenville, Illinois. The city is just one of the Chicago suburbs opposed to the recent Candian Pacific merger. Grist / John McCracken

Camanche, like many cities along the banks of the Mississippi, became a solidified community in the mid-19th century, relying on a commercial corridor sculptured by rails and barges to haul timber, clams, pork, and grain across the country.

Since the first tracks split through the city in 1857, the contents of trains have changed drastically. Alice Srp, who lives by the Mississippi River and has lived in Camanche for over 55 years, said she’s seen this shift in her lifetime.

“Rather than cargo containers and [lumber], these are round oil tankers,” Srp said.

Srp said the merger will make emergency response harder for the older population who live on the river side of the tracks. She also worries that, even if a future derailment isn’t fatal, an oil spill could become an ecological nightmare for the region, given that the tracks run parallel to the river.

Chemicals float on the surface of Leslie Run creek on February 25, 2023, in East Palestine, Ohio, a few weeks after a Norfolk Southern Railways train carrying toxic materials derailed nearby. Michael Swensen / Getty Images

Chemicals float on the surface of Leslie Run creek on February 25, 2023, in East Palestine, Ohio, a few weeks after a Norfolk Southern Railways train carrying toxic materials derailed nearby. Michael Swensen / Getty Images

In May, the dividing line between train tracks and the Mississippi blurred. Camanche saw its third-highest river levels in history, and parts of the tracks in town were underwater. Findings from the U.S. Department of Transportation and global research point to increased hazards and damages to railroads due to climate-fueled flooding.

While rail and water commerce compete for cargo, they often go hand in hand when it comes to location. According to Railfan & Railroad Magazine, railroads are historically built next to rivers to decrease grading and curves along a train’s route, and many routes across the country often followed the “natural courses of water.”

In May, the Mississippi River reached record levels in Camanche, swallowing some rail crossings and lines during flooding. Grist / John McCracken

In May, the Mississippi River reached record levels in Camanche, swallowing some rail crossings and lines during flooding. Grist / John McCrackenThe relationship between railroad corridors and rivers is likely to get more turbulent as flooding becomes more frequent due to a warming climate. In late April, a train derailed in Western Wisconsin along the Mississippi River during heavy rain, dumping train cars into the river.

Despite ongoing concerns about the impact of increased rail traffic on the Mississippi River, the Canadian Pacific and Kansas City rail merger continued. In its final environmental impact statement, the Office of Environmental Analysis for the STB wrote that the negative impacts of the merger would be “negligible, minor, and/or temporary.”

The office also found that the merger would increase the transportation of hazardous material on more than 5,800 miles of rail lines through 16 states, including Iowa, Illinois, and Ohio.

“You feel like you’re just run over and it doesn’t matter,” Srp said.

Residents in Camanche aren’t alone in their opposition to the merger.

Eight communities from Chicago suburbs formed the Coalition to Stop CPKC to oppose the merger. Chicago’s freight industry is the largest in the country and, according to the coalition, the merger will increase traffic by 300 percent in the next three years.

A red train car sits outside of the Camanche Historical Society Depot Museum. Camanche, like many towns along the Mississippi River, has always had strong connections to the rail industry. Grist / John McCracken

A red train car sits outside of the Camanche Historical Society Depot Museum. Camanche, like many towns along the Mississippi River, has always had strong connections to the rail industry. Grist / John McCracken

Despite the deal’s federal approval, these suburban communities are pushing back. On May 11, the Coalition to Stop CPKC filed an appeal to prevent the merger, citing a need to review the public safety and environmental impacts.

“The (Surface Transportation Board) ruling shows us three things,” said Jeff Pruyn, the mayor of Itasca, Illinois, a community two hours east of Camanche. “It ignored our concerns for the quality of life in our communities, it ignored our concerns about the negative consequences on economic development in our communities, and most importantly, it ignored our concerns for safety.”

When reached, the STB declined to comment for this story, citing the pending appeal litigation.

In Bensenville, Illinois, another community opposing the merger, the presence of the transportation sector divides the town. On one side, there are quaint bungalows, old-fashioned street lights, and a downtown with cobblestone streets and a commuter train station.

A sign marks the intersection of Railroad Avenue and York Road in Bensenville, Illinois. Grist / John McCracken

A sign marks the intersection of Railroad Avenue and York Road in Bensenville, Illinois. Grist / John McCracken

On the other side of Bensenville, a village of more than 18,000, sit two massive transportation facilities: Chicago O’Hare International Airport and the Bensenville Yard, a massive rail terminal. According to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, 50 percent of all freight trains in the country pass through Chicago’s varied rail corridors and terminals.

This terminal already sees a variety of cargo, including hazardous materials. On a Saturday morning in mid-May, a train of an estimated 150 cars made its way through Bensenville, headed to the terminal. Grist observed roughly nine train cars marked with a hazard placard for the industrial chemical styrene monomer, an explosive “probable human carcinogen” used to make rubber and other plastics.

There were also 11 train cars marked with a hazard placard for “Not Otherwise Specified” hazardous materials and at least 12 oil tankers with no visible hazard placard.

Safety is not only a concern for the cities and towns seeing increased rail traffic, but also for those working the rails. In the immediate aftermath of the Ohio derailment, the working conditions of railroaders were called into question.

Mark Burrows, a retired railroad engineer from Chicago, said the rail industry has been stretched thin and lacks adequate protection for workers. It suffered a blow to worker protections when President Biden signed a bill blocking a national rail strike last year. Rail, fossil fuel, and petrochemical companies celebrated the strike’s defeat.

Retired railroad engineer Mark Burrows says the rail industry has been stretched thin and lacks adequate protection for workers. Grist / John McCracken

Retired railroad engineer Mark Burrows says the rail industry has been stretched thin and lacks adequate protection for workers. Grist / John McCracken

Burrows said he’s seen the industry become increasingly consolidated, hurting the well-being of workers. He retired in 2015 after roughly four decades.

He said he saw an increase in oil tankers in his last years of working in the Chicago area and the Bensenville yard. It is possible that workers are more aware of the hazards they deal with daily, he said, but the “draconic and barbaric” working schedules and conditions have them operating at maximum capacity at all times, to avoid being penalized or worse.

“What we now know as Precision Scheduled Railroading just obliterates our normal working agreements,” said Burrows, a member of Railroad Workers United. “And it caused a speedup, having these guys work like maniacs.”

“Precision Scheduled Railroading” is a type of rail traffic management that focuses on increasing efficiency by reducing staff and lengthening trains.

For Burrows, derailments and poor working conditions are symptoms of the industry’s efforts to maximize profits.

He said that establishing better working conditions for staff, creating a nationalized railroad system, and reforming how hazardous materials are classified and transported could all prevent future disasters on the tracks.

“If you ask me what’s the definition of a hazardous train: If it is just one damn car of ammonia, or chlorine, or anything that’s uber hazardous, then that should be considered a hazardous train,” Burrows said. “Because all it takes is for one car to open up.”

About 1,000 miles west of Camanche, the sound of train horns worries Ingrid Wussow.

“I think we are at the precipice of a lot of devastating things if we don’t start making decisions that put our environment first,” she said.

Wussow, the newly elected mayor of Glenwood Springs, Colorado, has joined other surrounding municipalities in a push against expanding oil trains directly through her downtown.

A planned 88-mile railway expansion would connect the oil-rich Uinta Basin in Utah to Union Pacific rail lines, linking Western oil to Gulf Coast refineries.

A passenger train rolls along a rocky cliff face in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. Soon, the town may see a different kind of train pass through after a planned expansion opens up the route for oil tankers. Joe Raedle / Getty Images

A passenger train rolls along a rocky cliff face in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. Soon, the town may see a different kind of train pass through after a planned expansion opens up the route for oil tankers. Joe Raedle / Getty Images

While the new railway has been on the table since 2014, Wussow said that concerns over the shipment of hazards like oil have been renewed in recent months.

The increase in oil drilling and an expanded fossil fuel market flies in the face of global climate goals. This burning of fossil fuels will continue to exacerbate the climate crisis, resulting in extreme weather events such as flooding and mudslides.

Besides a potentially deadly derailment and oil train explosion in Glenwood Springs’ downtown district, Wussow shares the same concern as other environmental groups and municipal leaders in the region: increased oil by rail along the Colorado River. The expansion is estimated to ship 4.6 billion gallons of waxy crude oil per year through Colorado, a hundred miles of which would run right beside the river.

The Colorado River is the source of drinking water for roughly 40 million people and is currently experiencing a historic drought. Wussow said the river is the “lifeblood” of the region, drawing tourists and recreation throughout the year.

Wussow added that many residents would be put in danger by increased oil train traffic moving full speed through railroad towns. She said communities have already seen the risk posed by increased hazards on rail lines moving through their towns.

“East Palestine, Ohio, is an example of how damaging and concerning these derailments are,” she said.

In Camanche, the dangers of rail contents and the obstacles they pose to public safety aren’t lost on city administrator Andrew Kida, who doesn’t mince words when looking back on negotiations with Canadian Pacific.

“Canadian Pacific doesn’t give one rat’s behind about people,” Kida told Grist.

Andrew Kida, the city administrator for Camanche, sits in a conference room. He told Grist that the international rail company Canadian Pacific cares more about profits than people. Grist / John McCracken

Andrew Kida, the city administrator for Camanche, sits in a conference room. He told Grist that the international rail company Canadian Pacific cares more about profits than people. Grist / John McCracken

As part of the merger negotiations, the city of Camanche was offered, and its council eventually turned down, over $200,000 per railroad crossing to shut down up to three crossings. This would permanently close the sections of the road that intersect with the tracks. Camanche counter offered with $2.5 million and the railroad company declined. Larger cities accepted offers in the millions of dollars to shut down crossings.

Kida told Grist that he is now working on using Iowa state law to force the railroad companies to pay for infrastructure that would allow for better access for emergency response.

Kida said he would have preferred the oil that is now moving through his town be sent from Canada by pipeline, as a shale oil derailment in the nearby Mississippi River marshland would “make cleaning up the Exxon Valdez look like child’s play.”

“All they’ve done is taken the Keystone pipeline and put it on wheels and run it right next to the Mississippi River,” he said.

This article originally appeared in Grist at https://grist.org/transportation/camanche-railroad-merger-hazard-toxic-train-chemical/.

Grist is a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at Grist.org

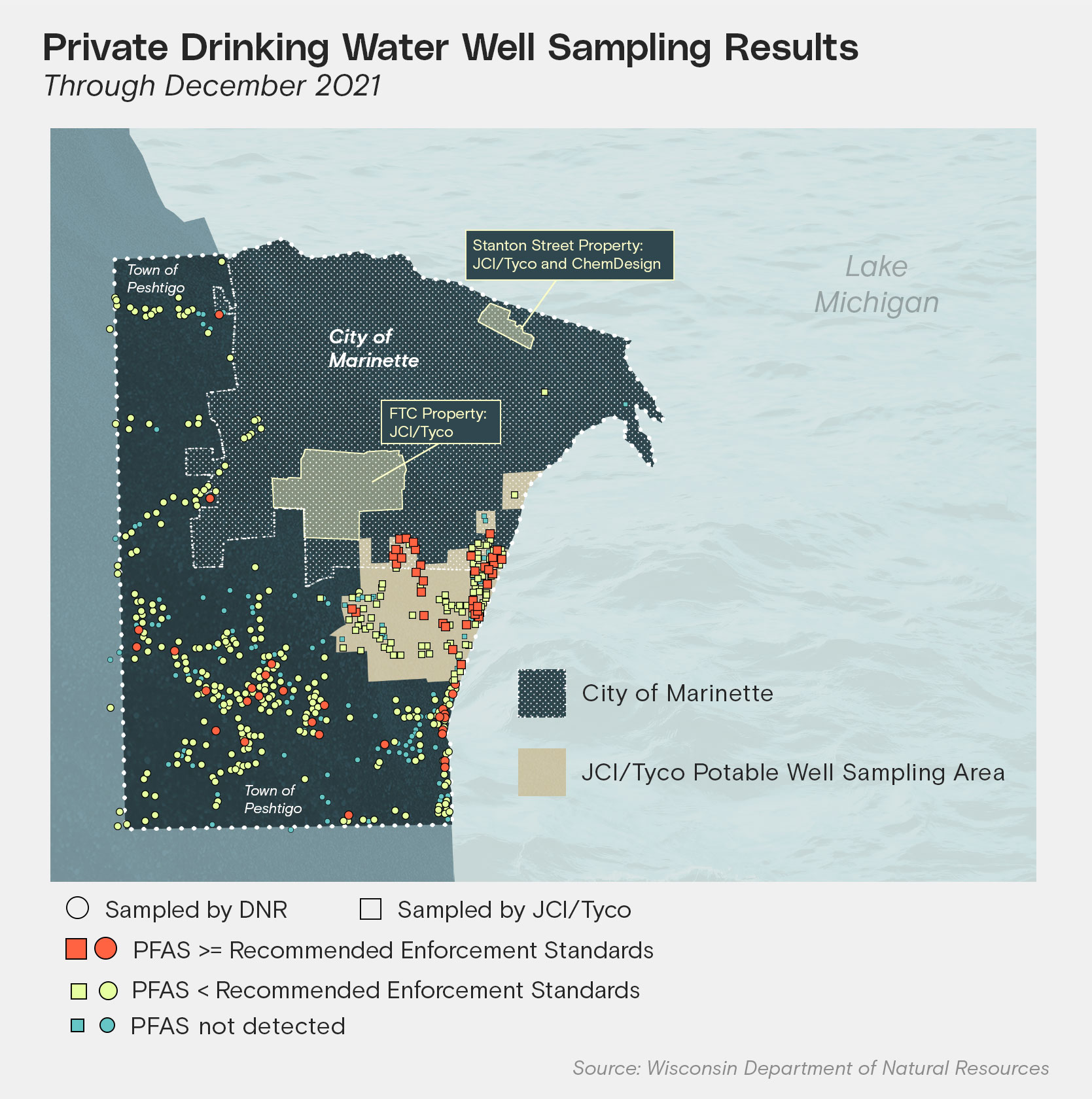

The entrance of Johnson Control’s Ansul Fire Technology Center can be seen in Marinette, Wisconsin, just outside of the town of Peshtigo. Previously known as Ansul, the company produced firefighting foam for decades in the region.

Grist / John McCracken

The entrance of Johnson Control’s Ansul Fire Technology Center can be seen in Marinette, Wisconsin, just outside of the town of Peshtigo. Previously known as Ansul, the company produced firefighting foam for decades in the region.

Grist / John McCracken Grist

Grist In an archive photo, workers from Madison, Wisconsin, test firefighting foam in 1965. Representatives from Ansul, the original Marinette, Wisconsin company now known as Tyco, were on site to test the foam. Wisconsin Historical Society

In an archive photo, workers from Madison, Wisconsin, test firefighting foam in 1965. Representatives from Ansul, the original Marinette, Wisconsin company now known as Tyco, were on site to test the foam. Wisconsin Historical Society A sign in Peshtigo warns of the dangers of touching and consuming the area’s water. The area’s creeks and groundwater have tested for PFAS upwards of 3,800 parts per trillion, or ppt, of the various chemicals. This level is over 54 times the state’s drinking water standard. Grist / John McCracken

A sign in Peshtigo warns of the dangers of touching and consuming the area’s water. The area’s creeks and groundwater have tested for PFAS upwards of 3,800 parts per trillion, or ppt, of the various chemicals. This level is over 54 times the state’s drinking water standard. Grist / John McCracken Workers can be seen drilling a new deep well in the town of Peshtigo. Tyco plans to cover the expenses of installation and other costs for the next 20 years, but not everyone in the area who have toxic PFAS chemicals in their wells will get one.

Tyco/JCI

Workers can be seen drilling a new deep well in the town of Peshtigo. Tyco plans to cover the expenses of installation and other costs for the next 20 years, but not everyone in the area who have toxic PFAS chemicals in their wells will get one.

Tyco/JCI On Kayla Furton’s lawn, a sign is displayed advocating for clean water in the town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin,. Furton’s home is within the potable well sample area, a designated zone created by the DNR where Tyco claims responsibility for PFAS pollution.

Grist / John McCracken

On Kayla Furton’s lawn, a sign is displayed advocating for clean water in the town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin,. Furton’s home is within the potable well sample area, a designated zone created by the DNR where Tyco claims responsibility for PFAS pollution.

Grist / John McCracken