'Traumatized': Women prosecuted for miscarriages at record levels

The day before Brittany Watts miscarried at home in Warren, Ohio, medical staff at Mercy Health-St. Joseph Warren Hospital told Watts that her nearly 21-week-old fetus had no chance of survival. And without treatment, neither would she.

On that, Watts’ attorneys and those representing the hospital she is now suing agree.

But Watts still ended up in jail two years ago, after leaving the hospital due to care delays and then returning in need of medical care but without a fetus.

While St. Joseph medical staff were treating Watts, a nurse was on the phone with police, speculating that Watts had birthed and then killed a live baby, according to a federal lawsuit filed earlier this year. The suit claims the hospital and individual staff were negligent and lied to police, and that police allegedly violated her civil rights.

Rachel Brady, an attorney and partner at Chicago law firm Loevy & Loevy, said that though the charges in Watts’ case — “abuse of a corpse,” after she had flushed the remains — were ultimately dropped, she has suffered lasting harms. After inadvertently becoming the public face of pregnancy criminalization in the post-Roe v. Wade era, she is among the first since the Dobbs decision to seek legal recourse for alleged civil rights violations.

“She found herself the unwilling face of this movement, and she has been traumatized by the entire event,” Brady said of Watts, who declined an interview. “This is every expectant mother’s worst nightmare. And rather than being able to grieve her loss, she was taken away in handcuffs. She was interrogated in her hospital bed while she was still tethered to IVs, and so she wants compensation for her own trauma, but most importantly, wants to make sure that this doesn’t happen to anyone else.”

In the three years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision struck down the federal right to abortion granted by Roe, women around the country have faced criminal charges after their pregnancies ended in miscarriage or stillbirth. Experts believe these cases have risen since states began banning abortion, though most often women are charged not under abortion bans but existing statutes including homicide, abandonment of a body and abuse of a corpse. And they believe these cases will continue to climb, as more prosecutors feel emboldened by state abortion bans; as more states consider laws that would give full legal rights to fetuses and embryos; and as more police investigate miscarriages as potential abortions.

“We are seeing more cases of pregnancy loss resulting in charges, certainly in the four-plus years that I’ve been at the organization,” said Dana Sussman, senior vice president of the legal nonprofit Pregnancy Justice, which researches pregnancy criminalization in the U.S. and helps defend people who have been charged with crimes related to their pregnancies. “Increasingly we are seeing law enforcement view pregnancy loss as a suspicious event — as a potentially criminal event — as opposed to a health concern, a health crisis.”

Women have faced pregnancy criminalization for decades, especially under drug laws and at a higher rate for those who are poor or people of color like Watts, who is Black. Pregnancy Justice has tracked more than 1,800 pregnancy-related arrests and detentions between 1973, when Roe v. Wade was decided, and 2022, when the decision was overturned. But in the first year after Dobbs, Pregnancy Justice documented 210 pregnancy-related prosecutions, the most they’d found in a single year since they started this research. And 22 cases involved pregnancy losses similar to Watts.

“It still remains a very, very, very tiny percentage of all people who experience pregnancy loss or who are pregnant, so I don’t want to create unwarranted fear,” Sussman said. “But one is too many, and 22 is certainly too many. And the more we normalize the idea that abortion is criminalized and your behavior during pregnancy is something that law enforcement can investigate, can make judgments about, can use as evidence against you, we will see more of these cases.”

Reproductive rights legal advocates say police have become increasingly suspicious of miscarriages, in states with bans, like Idaho, but also in states with more liberal abortion policies. The majority of states that allow abortion cut off access at between 22 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, which is an approximate estimate of when fetuses could survive outside of the uterus with medical intervention. An estimated 10% to 20% of known pregnancies end in miscarriage. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says it is difficult to determine the cause of a miscarriage or stillbirth.

According to Pregnancy Justice’s most recent numbers, Alabama prosecutes more pregnant people than any other state — 104 of 210 prosecutions in 2023. Many are concentrated in Etowah County, which in recent years has cracked down on drug use while pregnant, using a 2006 chemical endangerment law intended to protect children from meth labs, according to a 2023 AL.com analysis. The Etowah County District Attorney’s Office did not respond to a request for comment.

Sussman said evidence of direct harm caused by women in pregnancy-related prosecutions is often thin, and that these cases are often more about emotion than science. Some women who delivered stillbirths have been convicted of murder or manslaughter based on the hydrostatic lung test, also known as the lung float test, a widely discredited idea dating back centuries that involves putting fetal lungs in a container of water: If they float, the baby must have born alive, goes the theory. But medical examiners say these tests are deeply flawed and that air can enter the lungs of a stillbirth in many ways. After being sentenced to 30 years in prison on the basis of the lung float test, Moira Akers, of Columbia, Maryland, was this year ordered a new trial.

Sussman said serious charges are often dropped or reduced in the pregnancy loss cases, upon investigation and with autopsies, but by then, many of the harms of incarceration have already taken hold. She said charges can result in reputationally damaging news headlines, as well as loss of custody of their other children, housing and employment.

Rafa Kidvai is the director of If/When/How’s Repro Legal Defense Fund, which provides financial support for people investigated for pregnancy outcomes, including bail, bond, court fees, transportation and other expenses. They said the fund’s caseload has been rising since they began offering these services in 2022, with about 30 clients and more than $2.7 million paid in bail and bond. Kidvai said steep charges following a pregnancy loss — including manslaughter and murder — allow for high bails many cannot afford.

“The trends that I’ve seen are more cases in volume, higher bails, more intense prosecutions across the board, and the use of pregnancy as a factor, regardless of outcome, being used against someone,” Kidvai said, noting that newer laws around bail in states like Texas have made the Repro Legal Defense Fund’s work more challenging.

When Watts miscarried in September 2023, an Ohio abortion ban had already been blocked and abortion was legal until around 22 weeks’ gestation, right around the time Watts was losing her pregnancy. She was not charged under the abortion law but under a statute typically applied as an enhancement to murder.

“A lot of the cases in Ohio are, you kill somebody and dismember them in order to hide the body, or you kill somebody and set the body on fire in order to conceal it,” Brady said. “When you talk about abuse of a corpse, that’s what we’re talking about. We’re absolutely not, under any circumstances, talking about having the miscarriage and then disposing of the products of conception. That is very clearly not what this law is for or how it has historically been used.”

The city prosecutor who advanced Watts’ case took issue with how Watts disposed of the fetal remains, and how she “went on (with) her day,” though county prosecutors sided with the grand jury’s decision not to indict. But Watts’ personal situation continued in the public eye. She told the Tribune Chronicle she was “swatted” that first Christmas after her pregnancy loss.

Brady said that through discovery, Watts’ legal team is hoping to understand why there were alleged delays in Watts’ care within Mercy Health, which is a Catholic hospital system. Miscarriage care delays and denials have cropped up all over the country in the wake of state abortion bans, but also before Dobbs, especially at Catholic hospitals.

Attorneys representing the hospital and named medical staff, in its response brief, argue that Watts forfeited care when she signed a waiver and left against doctors’ advice. Watts claims she waited for several hours without miscarriage treatment before leaving the hospital two separate times, even after she’d agreed to doctors’ proposed treatment, which was to induce labor rather than give her a common second-trimester abortion procedure. Last year CBS News, after reviewing hundreds of medical records, reported that Watts waited for nearly 20 hours at the hospital over two days, begging to be induced while doctors waited for approval from an ethics team.

“There has to be a shift in the risk analysis here of what is more risky,” Sussman said. “Is it more risky to turn over your patient to law enforcement, or is it more risky to give the patient the care that she needs in the moment and not turn her over to law enforcement?”

More states propose adopting legal personhood for embryos, abortion-homicide laws

Many state abortion bans include an exemption from criminal prosecution for the pregnant person, but women who have had abortions have been prosecuted under other laws. A Nebraska teenager was sentenced to 90 days in jail after taking abortion pills her mother ordered online for burning and burying the fetal remains, under a law related to the removal of human remains.

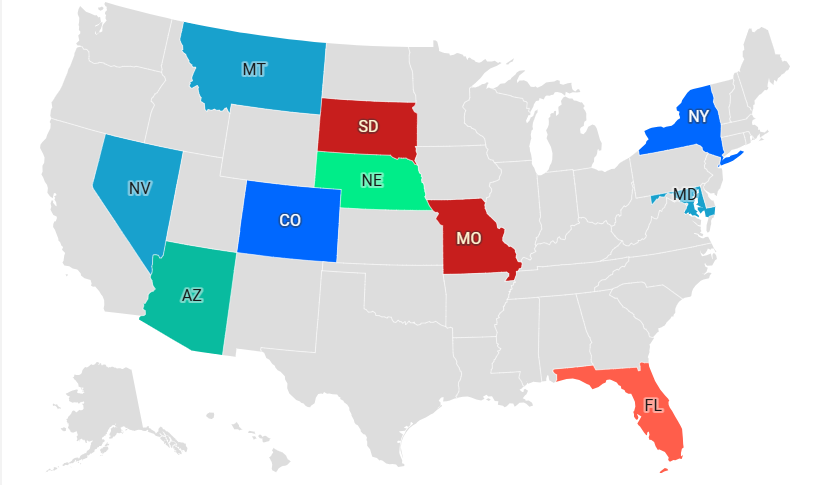

But for the past three years, an extremist faction of the anti-abortion movement has been trying to apply homicide charges to pregnant people in order to further curb abortion rates that have continued to climb, with the availability of abortion pills. This year, “equal protection” model bills crafted with the help of groups like Abolitionists Rising and the Foundation to Abolish Abortion, were introduced in several states, including: Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas. Most of these bills died in committee, but activists said they’ve seen more support from state lawmakers than in any other year.

“So far this year, 122 state lawmakers have sponsored equal protection bills, easily eclipsing every other past session,” said Bradley Pierce, a constitutional attorney and president of the Foundation to Abolish Abortion, in an email. He said 16 such bills were introduced in 14 states this year. “We had 21 initial bill sponsors in both Georgia and Texas, as well as 17 in Idaho. We also had 16 lawmakers vote for the bill on the floor of the North Dakota House, which is a new record.”

Pierce noted that recently the Oklahoma Republican Party censured four state lawmakers who voted against one of these bills in committee. He said these laws should not apply to miscarriages but that it would be under states’ criminal justice systems to handle cases of “suspected prenatal homicide.”

T. Russell Hunter, the executive director of Abolitionists Rising, based in Norman, Oklahoma, says induced abortions are indistinguishable from homicide, and he blames the more mainstream anti-abortion movement for opposing bills his organization pushes, which would subject women to homicide charges. A father who says he lost two children to miscarriage, Hunter said spontaneous miscarriages and stillbirths should not be prosecuted like abortions. But he supports investigations depending upon if the pregnant person used drugs, how they disposed of the fetal remains, and perceptions around their emotions.

“I don’t think that all miscarriages need to be investigated,” Hunter said. “One, people who actually have miscarriages are terribly sad. You know immediately; it’s not like you have to investigate this person.”

Students for Life of America CEO Kristian Hawkins calls the abortion abolitionists “pro-prosecutionists” and says they are detrimental to the anti-abortion movement. The organization did not respond to an interview request, but on her podcast, Hawkins said women should not be prosecuted for having abortions — until culture and more laws have changed.

“There’s those who say prosecute women and abortionists now. There’s those who say prosecute the abortionist now and perhaps women later, after culture and laws are changed. And then there’s a third class of folks that’ll say never prosecute women but you can prosecute abortionists now or later,” Hawkins said. “The vast majority of us, including myself, in the pro-life movement are in that mid-category, because that makes the most logical sense. It allows us to move the ball forward in good faith to save as many lives as we can right now while working to change culture, elect actual political leaders who will agree with us.”

More states are passing laws that could potentially lead to investigations at the same time that a federal judge recently struck down a federal health privacy rule for legal abortion care. West Virginia Gov. Patrick Morrisey recently signed into law House Bill 2871, which expands the vehicular homicide offense to include aggravated vehicular homicide and clarifies that victims can include embryos and fetuses. The West Virginia Prosecuting Attorneys Association recently said women who miscarry are not required to notify law enforcement or face potential criminal prosecution, after a prosecutor warned that residents who miscarry could face criminal charges under the state’s strict abortion ban.

At least 38 bills containing personhood language have been introduced across 24 states this year, according to a new report from the State Innovation Exchange and Guttmacher Institute, both of which support abortion rights. Personhood language in some state laws has allowed prosecutors to push for harsher sentences when pregnant women are killed, abused or injured. But the laws have also allowed women to be prosecuted for child endangerment for substance use while pregnant. And experts say these laws could also enable states to force medical interventions against a pregnant person’s will.

Moving in the opposite direction, this year, Washington Gov. Bob Ferguson signed into law the Dignity in Pregnancy Loss Act, to prevent the criminalization of pregnancy outcomes, outside of unlawful or suspicious circumstances, similar to California’s. It also requires jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers to report pregnancy losses to the state annually.

Daniel Grossman (UCSF.edu)

Daniel Grossman (UCSF.edu)