What it looks like when a black hole eats a star

Without stars, our universe would be a much darker, colder place. These balls of plasmic hydrogen and helium gas not only blast heat and light, they come in a stunning array of colors, chemical composition and size. And "big" doesn't begin to describe them. Our sun is 109 times larger than our planet. But our star isn't so special — it's technically average-sized. Some stars, like UY Scuti, an extreme red hypergiant in the constellation Scutum, have a radius 1,700 times our sun, which could fit inside it almost 5 billion times. Compared to UY Scuti, our favorite star is a speck of dust.

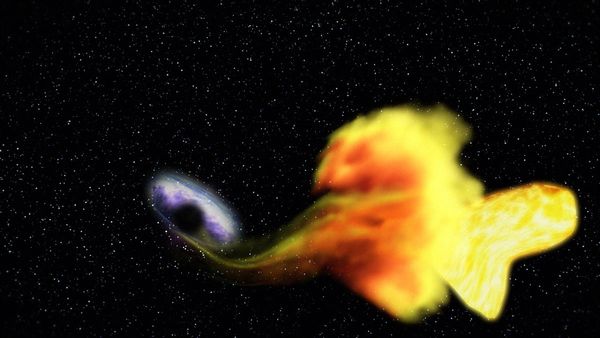

A black hole devouring a star (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/CI Lab)

So it's a little disturbing thinking about a star getting shredded to bits with the same ease someone chomps into a stringy chunk of saltwater taffy. (That's also sorta what it looks like, as we'll get into.) A recent analysis has given astronomers a clearer look at the horror that occurs when star meets black hole and the results will make anyone glad these things are nowhere near us.

But first, briefly, what is a black hole? Though they can form in other ways, black holes are typically formed when a star dies and collapses in on its own gravity. Black holes are star corpses. We can think of them as massive whirlpools, and just like a rubber ducky will circle the drain, anything that "swims" too close to a black hole will get sucked in the spin cycle of death. The pull is so strong even light cannot escape, making it extremely difficult to photograph, not to mention the immense distances and breathtaking speed that factors into anything space-related. But astronomers are getting a lot better at snapshots of these weird dead stars.

While the James Webb Space Telescope has been getting a lot of attention for its stunning astrophotography — and for damn good reason — the Hubble Space telescope isn't out of commission just yet. In January, NASA announced that Hubble caught a black hole in the act of devouring a star, swirling it into a donut shape the size of our solar system.

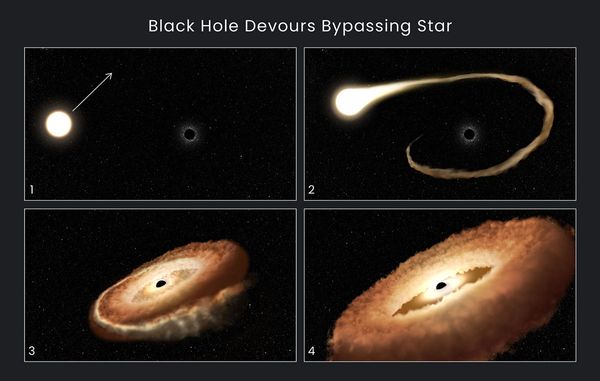

This sequence of artist's illustrations shows how a black hole can devour a bypassing star. (NASA, ESA, Leah Hustak (STScI))

Around 300 million lightyears away from us, at the core of a galaxy obliquely named ESO 583-G004, a supermassive black hole caught a star in its grisly orbit, and began to unravel it like a spool of cotton candy. Hubble caught the resulting burst of ultraviolet light, an explosive event known as a tidal disruption event (TDE).

A TDE may sound like when a toxic algae bloom forces a beach closure, but these are actually some of the brightest phenomenon in the known universe. As the star is unspooled around the black hole, it creates immense pressure on the gas and dust from the star, with temperatures reaching thousands of degrees, discharging luminous flares that can be seen millions of miles away.

Astronomers have previously captured about 100 different TDEs, but usually after a black hole has already torn everything to shreds. The recent snapshots from Hubble demonstrate changes in the ill-fated star's life over the course of days or months and before things got especially heated.

"Typically, these events are hard to observe. You get maybe a few observations at the beginning of the disruption when it's really bright," Peter Maksym, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said in a statement. At this stage in its execution, the star resembles a giant donut or a fluffy steering wheel cover in a lowrider music video.

"We're looking somewhere on the edge of that donut. We're seeing a stellar wind from the black hole sweeping over the surface that's being projected towards us at speeds of 20 million miles per hour (three percent the speed of light)," Maksym said. "We really are still getting our heads around the event. You shred the star and then it's got this material that's making its way into the black hole. And so you've got models where you think you know what is going on, and then you've got what you actually see. This is an exciting place for scientists to be: right at the interface of the known and the unknown."