These Oklahomans needed mental health care. Instead, they died in jail.

Lena Corona was sitting on the porch of her Seminole home, blood dripping from her hand, when police arrived at 2:45 a.m. Her dad stood behind her, pressing a T-shirt over the wound on his chest where Corona had plunged a shard of glass.

When he called 911 on July 10, Freddy Corona hoped police would take his teenage daughter to the hospital as they had done fewer than 24 hours earlier when she threatened him with a metal rod while in psychosis. But over her dad’s objections, the police arrested the 18-year-old for assault and battery with a deadly weapon.

At St. Anthony Hospital, officers sought medical care for the cut on Lena Corona’s hand. Corona told emergency room nurses that she was defending herself from dark spirits, according to Cpl. Melissa Sharp’s incident report. After medical staff cleared Corona, Sharp drove her to the Seminole County jail where she was admitted while still in psychosis, a symptom of her diagnosed mental illness.

Hours after Corona was booked into jail, her sister called and told a jailer that Corona had been prescribed medication for her bipolar 1 disorder the last time she was hospitalized but had stopped taking it triggering psychosis. She asked the jailer to make sure her sister received treatment. She responded by telling her Corona’s bail was $7,500, money the family didn’t have.

Shawna Normali held up her favorite photo of her daughter, Lena Corona. (Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch)

Across the state and country, families like the Coronas can't access sufficient health care for their loved ones and turn to for help from police in a crisis. With law enforcement involved, emergency situations can escalate quickly, leading to arrests and incarceration in jails where detention officers with minimal training are responsible for the health and safety of detainees, which can have fatal consequences.

“I thought a couple of days in there would be OK,” Freddy Corona said. “At least she’d be safe in there for a few days until we could figure everything out. Instead, she just got worse and worse and no one did anything to help her.”

Five days into her jail stay, on July 15, Lena Corona hanged herself in a cell.

State laws guiding mental health and addiction care in jails are vague, leaving it up to jail officials to decide how often to check on sick or suicidal detainees, or when to seek emergency treatment. Behind bars, presumed-innocent people with mental health conditions often face neglect, abuse, or even death.

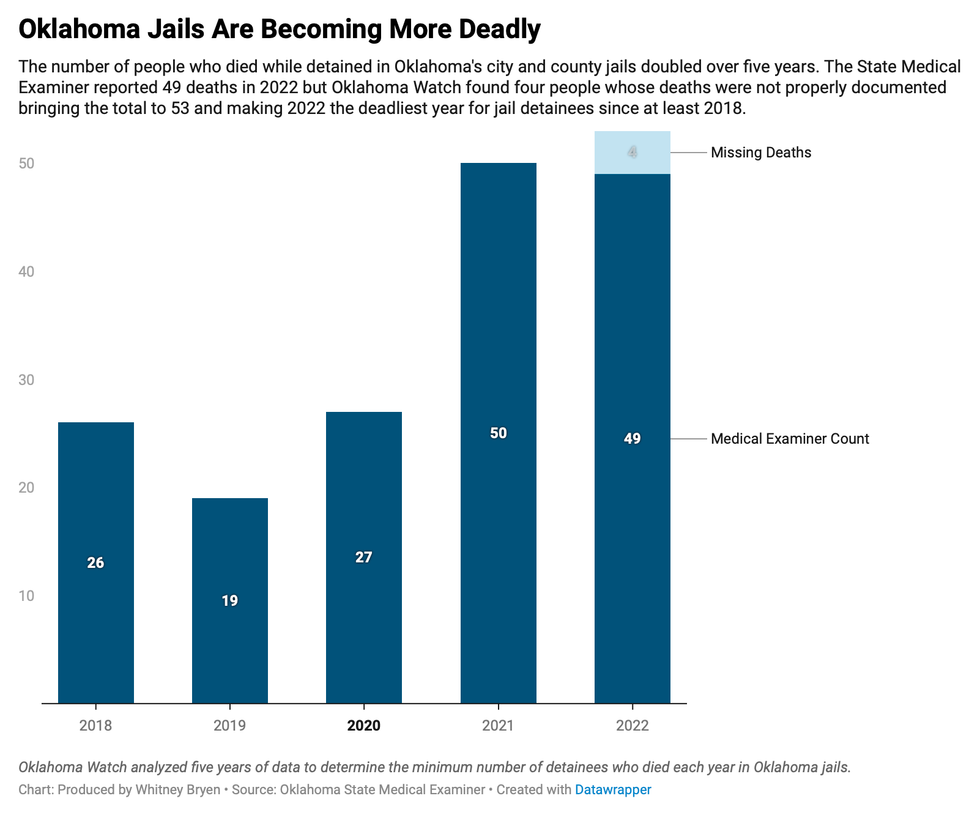

Last year, 28 jail detainees died from untreated mental health or substance use conditions, accounting for more than half of the state’s 53 jail deaths, an Oklahoma Watch investigation found.

Accountability for the mistreatment and deaths of detainees is minimal in Oklahoma. The state agency that inspects jails has limited enforcement power under the law. A recent Oklahoma Watch investigation found that local oversight can be lax without a central entity ensuring care for or tracking vulnerable detainees.

State and federal laws require jails to report detainee deaths and suicide attempts, but not every jail complies. A recent Oklahoma Watch investigation found that the Pottawatomie County jail failed to report at least six deaths to the State Health Department since 2017 with no consequences for jail officials. Last month, trustees promoted the jail’s second in command, who is responsible for investigating deaths and is married to the jail director.

The State Medical Examiner’s Office also tracks jail deaths, but employees are inconsistent in how they label those deaths, resulting in incomplete data.

The District Attorney’s Council reports jail deaths submitted by the health department and the medical examiner to the Department of Justice. It reported 26 deaths. Oklahoma Watch identified 53.

This year, Oklahoma Watch launched an investigation to determine who died in Oklahoma jails in 2022, how they ended up there in the first place and what killed them. Knowing how many people died and what happened to them is vital to preventing future deaths, said Jeff Dismukes, who retired this year from the state Department of Mental Health and runs the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, a group that supports people with mood disorders.

“No one cares enough about this issue to ensure that we have those records,” Dismukes said. “We clearly have the entities in place to do that kind of tracking and it could give us some answers if someone cared enough to advocate for these people.”

Triage, not treatment

The prevalence of mental illness and substance abuse is widespread in Oklahoma, with some of the nation’s highest rates of childhood trauma, domestic violence and incarceration contributing.

More than one in four Oklahomans 18 and older experienced mental illness in the past year and one in six reported having a substance use disorder, according to the 2023 State of Mental Health in America report.

Long waits and high prices for treatment mean many Oklahomans, especially those who are low-income and reliant on social services, often don’t receive help until they’re in crisis, triggering a response from police that can lead to incarceration instead of care.

Nearly everyone locked up in Oklahoma’s county jails need mental health or addiction treatment that jailers aren’t qualified to provide, said Ray McNair, director of the Oklahoma Sheriff’s Association.

“A county jail’s purpose is to maintain someone’s health, to keep them at the level they’re at and prevent them from getting worse while they work through the court system, not to treat them,” McNair said. “What jails are doing is triage until we can get them out.”

Without treatment, there isn’t a Band-Aid big enough to stop the deterioration of detainees with serious mental illness or addiction issues, McNair said.

For crisis response, cops are the default

Oklahoma police departments have reported a growing number of emergency calls from panicked families and concerned observers. Last year, Oklahoma City police responded to more than 18,700 mental health calls. Employees at the Tulsa, Edmond and Stillwater police departments said they don’t track mental health calls but officers respond to mental health emergencies daily.

The state Mental Health Department offers specialized crisis intervention training to help law enforcement identify signs of mental illness and addiction and teach officers to employ patience and compassion to avoid arresting people who would be better served at a treatment center. The training is voluntary, however, and certified officers are not always available to respond to crisis calls.

Co-response programs deployed by the Oklahoma City and Tulsa police departments are part of a growing, national trend to send mental health professionals on crisis calls with officers to de-escalate tense situations and reduce unnecessary arrests. But they can’t keep up with the volume of calls.

During a role-playing training exercise, Blanchard police officer Tawny McClintock assessed a man who is preaching loudly outside of a business, played by Norman Police Lt. Cary Bryant. These scenarios are the culmination of a 40-hour crisis intervention training that teaches law enforcement officers how to recognize and respond to mental health crises. (Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch)

Waiting for care can be deadly

Once at a jail, state law requires staff to survey detainees noting signs of mental distress, drug use or withdrawal. Detention officers’ ability to detect symptoms, and the candor of detainees, determines who receives medical or mental health care, increased supervision or is housed alone.

When Corona was booked into the Seminole County jail, she refused to answer questions from jailers, was agitated and would not cooperate with staff, according to her booking report. Jail staff were unable to take her mugshots or fingerprints or remove the necklace she was wearing.

Even when jail staff do identify a mental health need, care isn’t always accessible.

Few Oklahoma jails have counselors, psychologists or psychiatrists on staff so they rely on state-funded treatment centers. Rural jails are least likely to have mental health practitioners on staff or have nearby providers to call on for help. Nearly 40% of providers surveyed by Healthy Minds Policy Initiative reported having weeks- or months-long waits for appointments, which could be the difference between life and death for people behind bars.

Shannon Hanchett, left, and Kathryn Milano, right. (Photos provided)

In December 2022, hours before an evaluation from Griffin Memorial Hospital, Norman mother and baker Shannon Hanchett died at the Cleveland County jail where she was taken during a mental health crisis. Less than two weeks later, Noble grandmother Kathryn Milano died waiting for a court-ordered competency assessment at the same jail, which contracts with Turn Key Health Clinic to provide medical and mental health care to detainees.

Many jails statewide are housing Oklahomans deemed incompetent to stand trial who are waiting for a bed to become available at a state facility. In March, the Oklahoma Disability Law Center filed a federal class-action lawsuit against mental-health officials on behalf of Oklahomans who are languishing in county jails while awaiting court-ordered care.

The state Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services is providing medication, counseling, therapy and education to 231 detainees in 60 county jails instead of moving them to a state hospital, department spokeswoman Bonnie Campo said.

Tulsa County Sheriff Vic Regalado

Tulsa County jail is one of the holdouts. Sheriff Vic Regalado won’t allow competency treatment in his jail, despite having a wing dedicated to detainees with mental illness and staff trained in crisis intervention.

“It has been well established that jails are not the place to treat our mentally ill,” Regalado said. “These people are languishing in jails, often for a year or more, while the state is passing the buck to counties instead of spending money on short-, medium- and long-term facilities to alleviate the problem. I think this opens the door for widespread litigation and we’re not going to be a part of that.”

‘These are people, too’

Jailers regularly have feces thrown at them by detainees who are in mental distress. They’re berated and threatened daily. It’s common for officers to become desensitized over time and employ coping mechanisms that can seem animalistic. That makes training critical, said Jennifer Sullivan, who teaches jailers best practices for keeping people with trauma or mental illness safe.

State law requires detention officers responsible for the lives of detainees to receive 24 hours of basic training. Most county jails provide new hires with a 32- or 40-hour course developed by the Sheriff’s Association. Mental illness and addiction is part of every session, but three hours are dedicated to mental health and seven to substance abuse and detoxification.

Sullivan provides more in-depth training on how to communicate with detainees in crisis through classes offered by Mental Health Association Oklahoma. In the past five years, the nonprofit has trained 155 detention officers across the state in crisis intervention, trauma response and suicide prevention. Sullivan said jails have been resistant to the training, partly because high turnover leaves jails starting over with new trainees every few months.

“My light came on over Kesha. She needed help and we knew it. And we knew it would be weeks or months or even years before she got the treatment she really needed, if ever. I knew we could do more for these people and that’s what we did.”

Payne County Jail Director Reese Lane

In Oklahoma, jailers’ pay is about $14 per hour, causing the highest turnover rates McNair has seen in his 20 years at the Sheriff’s Association, which trains and advocates for jail staff and the sheriffs who oversee them.

“I’ve had sheriffs tell me when a new Casey’s moves into town, they lose people to the convenience store, which pays more money and there’s no abuse from detainees,” McNair said. “And they’re taking a big risk at the jail that if someone is injured or dies they could be held liable, so that on top of the low pay is really tough.”

Ronald Given

Ronald Given, a 42-year-old member of the Kiowa Tribe, resisted when detention officers attempted to restrain him during a mental health crisis at the Pottawatomie County jail 30 miles east of Oklahoma City. He died in 2019 from injuries sustained during the six-minute struggle, according to an autopsy report that ruled his death a homicide. State law enforcement investigated his death and friends and family are calling for accountability. The local district attorney reopened the case this year. So far, no one has been prosecuted.

Amid the challenging working conditions, jailers need to be reminded that the detainees in their care are someone’s parent, child or sibling, Sullivan said.

“We’re asking them to stop and think, ‘What would I want if this was my family member?’” Sullivan said. “Sometimes, they just need to be reminded that these are people too.”

Seeking alternatives

A Payne County jailer held Kesha Carter’s head up for her mugshot when she was booked into the jail an hour west of Tulsa in 2012.

Carter was under emergency detention for mental health treatment at Stillwater Medical Center when police arrested her for attempting to kick a doctor while she was handcuffed to a gurney, according to a police incident report.

Seven hours after she was booked into jail, Carter died by suicide.

“My light came on over Kesha,” jail director Reese Lane said. “She needed help and we knew it. And we knew it would be weeks or months or even years before she got the treatment she really needed, if ever. I knew we could do more for these people and that’s what we did.”

Naomi Wilson, program coordinator at Payne County Jail, taught a parenting class to women detained at the jail. (Photo provided)

Naomi Wilson, program coordinator at Payne County Jail, taught a parenting class to women detained at the jail. (Photo provided)For more than a decade, Lane has been building a team of mental health professionals and training his staff at the Payne County jail to go beyond the required assessments and supervision.

Linda Evans, a licensed psychologist and marriage and family therapist who works for the jail’s healthcare provider, Turn Key Health, treats mentally ill detainees and ensures they have swift access to their medications. Therapy is provided twice a week by a counselor and Oklahoma State University students studying to be counselors. A program specialist helps detainees study for their GED and teaches them about addiction, self-esteem, parenting, job skills and teamwork. And a peer support specialist from Grand Mental Health visits the jail daily, assisting detainees in court and making plans for care after they’re released.

Partnering with other county agencies, law enforcement, mental health centers and other community resources, like the university, costs the jail little to no money, Lane said.

Sometimes, though, people still fall through the cracks. Michael King, a 49-year-old father and handyman, died by suicide on Nov. 18, 2022, two days after being booked into the Payne County jail, according to a health department incident report. Jail spokesman Rockford Brown said King was not identified as a suicide risk when he was booked into the jail.

For families who have lost loved ones, questions linger about what more could have been done. Some are turning to the courts for help.

Bella Rose's fireplace mantel is covered in family photos, artwork and urns the hold the ashes of her sister, Lena Corona. (Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch)

Corona’s parents said they will file a lawsuit against the Seminole County jail before the end of the year. They hope a judge will ensure better care for people like their daughter and the 28 people who died in Oklahoma jails last year waiting for treatment.

“Every jail in the country could be better regardless of funding or their rural nature,” Lane said. “Every jail has a mental health provider somewhere in their area that they could be partnering with. They’re going to have to get honest with themselves and decide whether they’re willing to do the work to help these people.”

Oklahoma Watch is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity and newsrooms in select states across the country.

This article first appeared on Oklahoma Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons license. ![]()