Originally published by The 19th

Saturday marks the 49th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, the landmark ruling that guaranteed the right to an abortion. It could very well be the last anniversary before it is overturned.

During oral arguments for Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization last year, a majority of the court appeared ready to overturn Roe v. Wade, allowing states to ban abortion entirely. A decision is expected this summer.

Such a reversal would be historic. Prior to Roe v. Wade, people seeking abortions were forced to find clandestine clinics, borrow spare cash and travel hundreds of miles — sometimes under cover of darkness — for risky procedures that they learned about through word of mouth. There was the lingering worry that a procedure might not work. And, if it did, that it could result in medical complications — or even death.

Few expect the United States to revert to 1972. Unlike before Roe v. Wade, many Democratic-led states are now likely to pass laws cementing abortion protections, creating oases of access to the procedure in safe, legal settings.

And the advent of medication abortion pills could give people a safer way to end a pregnancy at home, even if their state has ended legal access. But “self-managed abortions” are only possible before 10 weeks of pregnancy, and also may not be accessible to everyone who wants to end a pregnancy. For people who don’t have these options available, the memories of life before 1973 carry particular salience.

With national abortion protections hanging by a thread, stories of a pre-Roe v. Wade nation matter now perhaps more than ever. To better understand the decision’s impact The 19th spoke with people across the country about their memories of life before the 1973 decision, as well as how things have changed in the years since.

These are memories from women who received illegal abortions, those who campaigned against abortion rights, and those who worked as health care providers before and after 1973. Below are their stories, in their own words.

Susie Scott, 73, of Laramie, Wyoming

(Rena Li for The 19th)

(Rena Li for The 19th)

It was spring in my sophomore year in college [in 1968] and I was here in Laramie, at Wyoming University. The word was in Laramie — because we’re quite close to the Colorado-Wyoming border, it’s about 50 miles — that if you knew the right folks, you could drive to Colorado [where doctors might provide illegal abortions].

I was in a relationship with a man I had essentially been with since 7th grade. I did not take the decision of what to do lightly. When it became evident that we were not going to get married, I started inquiring as to what, how, when, where. I had a sorority sister at the time who was from Colorado, and I took her aside and we had a conversation. She had just had a friend who was in Denver who was in the same situation I was.

There was kind of a third party that I found out about this provider in Colorado. I called and of course the first thing, right up front, was that all procedures were to be paid in cash, up front. If I recall right, it was like $575. Where does a college student find an extra $575 in 1968?

It was my money, the young man’s money, and money from some of our friends. There were very, very few people who knew about the predicament. In those days, it was considered really risky. And so you can count on one hand the people that I was telling. A friend offered to drive me to Denver and the instructions were that I was to register at the hotel, motel thing not far from this provider’s office in northern Denver. Register there. And after the procedure, I was to go back and spend the evening in the motel and come back and see him in the morning.

I went in the back door, and I remember just being scared to death, absolutely scared to death because I didn’t know what to expect. They were going to inject me with some sort of solution that would in a few hours result in a miscarriage, if you will.

So I gave the money. I had the procedure. And my friend and I went back to the motel. A few hours into the evening, nothing was happening. Nothing. And I thought, ‘Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear, I’ve just handed this fellow $575 and maybe this whole thing was a hoax.’

I said to my friend, “I want to go back to Laramie. I’m incredibly uncomfortable here. I’m scared to death. Let’s just get back to Laramie.” So we got the car, drove back to Laramie, and about the time we got to the outskirts of town — which means it’s almost sunrise — I started having contractions that went through the entire day. The following night, without having passed a fetus, I got scared and thought, ‘What in the world?’

So my friend drove me to the hospital, and I spent the next two days in the hospital. Fortunately, it was the end of the school year, so people were moving out of the sorority house. Lots of activity, nobody really realized that I was gone for a couple of days. The physicians or the providers, the hospital kept pressuring me to tell them what had happened. They thought I had sought an abortion.

One of the providers — and he was a provider here for a long, long time — very well respected, he came to my bedside and said, ‘Susie. If you don’t pass the fetus here in the next few hours, we’re going to have to have a surgical procedure.’ You know, you’re there. What do you say? Luckily, I passed it. That was it.

The follow-up on that is then I had a hefty bill at the hospital. I went to the hospital, worked out a payment plan with them. And I think I paid over like a year and a half. I eventually got it all paid off. But just the whole process was frightening.

About four years later, I was working in Denver. I got on an elevator and there was the doctor [who had performed the abortion]. I remembered his face. I just, you know, punched the next floor and got off the elevator.

He was very scary. My take was that in a strange way, he got pleasure out of the fact that I was at his mercy.

Suzie H., 75, Lincoln, Nebraska

I lived in New York City. I went to nursing school there, and then I worked there for a couple years. But when I was there, there were rumblings. It was the early ‘70s — ‘71, ‘72. And of course, Roe v. Wade passed in, I believe it was ‘73. I really didn’t have any thoughts about it one way or another. I wasn’t really sure how I felt about it at that time.

Because of an illness of my mother, I moved. I had to leave my job teaching at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, out to Crawford, Nebraska. And if you want to look on the map of Nebraska, it’s in the northwest part of the state, in the panhandle — very far away from any city.

I was planning to go back. And then I met my husband out there, and long story short, I got pregnant, and I was not married. I went to the doctor, and it was just after Roe v. Wade was passed in January. The doctor told me, “Well, I can refer you to a doctor up in South Dakota who does abortions.”

I came back and I told my husband-to-be, and we both decided that, no, that’s probably not a good idea. It’s our baby. We won’t do it.

I felt that it was my fault, my responsibility. And then when my daughter was born, it was like, “Oh, man, I would have felt terrible, I would have felt so guilty.”

From then on, I was very, very much a pro-life person. I joined a pro-life organization, and later on, when we moved to another town, I would give talks about [my experience].

One time, I was having lunch with a woman, she was actually a pastor’s wife. She was telling me that she was very much pro-abortion and was going on and on. I was very upset. I wanted to say something to her. And I said to myself, “OK, God, tell me what to say.” And he actually zipped my lips, and I just listened to her. Didn’t change my mind.

Then a couple years later, I was in Lincoln, Nebraska. I’m having lunch with some colleagues and the topic came up again. And one of my colleagues was talking about a relative who was getting an abortion. And I said to her, “Why are you supporting this?” She told me her story. And then she asked me my story and why I was so adamantly opposed. And I told her. The bottom line, we both kind of understood each other better. Over the years, I’ve come to understand that I am not the only one with a story — that other people have stories. There are sometimes good reasons.

Over the years, I’ve come to understand that I am not the only one with a story — that other people have stories.

Now, the other side of that coin is I still am not in favor of abortion as a means of birth control. But I think there are occasions when it is something that is the best choice, whether it be a health care issue or whatever. I do not have a condemning attitude, if you will. I’ve totally changed in how I feel toward people who have one, because I know the misery and the struggles of women who have had abortions, what they have gone through. It’s been terrible.

I don’t know if it’s a maturation in my mind, or if it’s just God telling me, “This is the real world. And this is how other people live their lives.”

I feel [abortion] still needs to remain a right. But one of the big things that needs to be offered more than anything is support for women who are pregnant. Say they were raped or they got pregnant, stupidly, like I did. We need to have more support than just say, “Oh, we’ll make an appointment, you can get an abortion.” We need to say “No, let’s have some counseling for you.” Let’s provide them with financial support, instead of just outright saying this is the only solution we have. There needs to be that right [to an abortion], but there needs to be constraints around that, and supportive measures.

I remember that before — there were illegal abortions going on that were deadly, to be honest. Back in the ‘70s, ‘60s. If they overturn Roe v. Wade, I am definitely concerned about that.

Lorraine Saulino-Klein, 72, Laramie, Wyoming

Lorraine Saulino-Klein, middle, in a photo from nursing school. (Rena Li for The 19th)

Lorraine Saulino-Klein, middle, in a photo from nursing school. (Rena Li for The 19th)

I graduated in 1967 from high school, and I went straight into nursing. I wasn’t even aware of the abortion laws in New York. I mean, you heard stories of people who were going to some back rooms or doctors. We had heard stories about that happening.

Then somebody would disappear. There was a hush she was pregnant and she’d be away. So we didn’t know whether she went to an aunt to have a baby or was pushed off somewhere to have an abortion. But everything was hush hush. We didn’t talk about it at all.

When I was 18, I went right to nursing school at Brooklyn, New York: Kings County Hospital Center School of Nursing. It was a three-year diploma school. We got these pink lab coats and we were supposed to talk to [patients]. Everybody I knew in my circle of new friends got old people. I was assigned to a 16-year-old.

I walk into the room, and there were like six or eight doctors standing around this beautiful looking girl. I mean I’m 18, she’s 16. And her eyes are rolled back. She’s thrashing all over the bed. And all these docs are totally helpless. This kid was pregnant. She went for a pill. And then she went for a coat hanger, because she wasn’t sure it was working.

She was a Catholic kid. She didn’t have anybody or anywhere to go, she didn’t know where to look for help. And here are these doctors, and I’m in charge of taking temperature. The temperature is going up. It gets to 107.

Oh, it was the most horrible thing I have ever seen in my life.

She dies in front of all of these doctors, and they’re helpless to do anything to help. They wanted to. There was just nothing they could do.

I was a Catholic teen. I took the Eucharist from the minister, I was very participatory. However, up until that point, I had never heard the Catholic philosophy that life begins at conception. I mean, it was just never something that came up. And I didn’t even hear that until I was 21.

But right then and there I thought no one, no matter what kind of mistake or goof-up or whatnot they did in their life, they shouldn’t have to suffer and die like that. It’s not a baby, it’s a fetus. The fetus died. She died.

I will for my whole life never forget it. It traumatized me.

It was devastating doctors, devastating nurses to cry. It was a nightmare. And I will for my whole life never forget it. It traumatized me. But it made me firmly in the camp that no matter what you do in your life, nobody should have to go through that. I mean, it didn’t only hurt that kid and that fetus. The doctors and nurses, too — they were too paralyzed to do anything.

I had a talk with someone that I knew, it was a friend of mine. And I said to her, “Did you ever see somebody die of a septic abortion?” And she said, “Well, let me think about that.” And I said, “Oh no. No, no. If you see anybody die like that, you never forget it.”

Rosalyn Jonas, 75, Bethesda, Maryland

The illegal abortion was in 1966. I had just turned 20.

It was the first guy I slept with, and I did not know shit about birth control or any other thing. I was 19 when I got pregnant and 20 when I realized that. I was living at home and with deeply conservative parents who I simply could not tell. I had a very good friend who was at Goucher College, in Towson, Maryland. It was a girls’ school and they had a network, a pipeline to a gynecologist in Baltimore.

So I got myself to Baltimore. [The gynecologist] was a lovely lady. And she said, “Can you tell your parents?” And I said ‘No.’ Then she gave me a little tiny folded piece of paper with a phone number on it. And she said, “Call this number.”

So I drove home. And I have to go to a payphone of course, to dial the number, because my mother was given to listening in on my calls. I call the number and some guy answers, and the arrangements are made — it’s supposed to be $600 in cash. We agree on a date and a pickup point, which was on Eutaw Street in downtown Baltimore, in front of a movie theater. We pick the date and the time. And then I have to find $600. I don’t have $600. I mean, that was a lot of money in 1966.

So I borrowed $100 here and $50 there. The day before the abortion, I was $200 short. This boy was just a real prick, so I called his parents. They gave him $600 and he gave me $200 that I was short.

He did drive me to Eutaw Street, and I stood there waiting to be picked up. Finally, a man in a sedan with a dog in the backseat pulls up. He could have been a serial killer, but he had a dog. That’s how you knew it must be OK.

I get in the backseat, and we drive out to Baltimore County, I don’t know where, to a farmhouse. There was a couple in the farmhouse. They laid me down on a table and gave me a mask. I had no anesthesia. After a while somebody I presumed to be a doctor comes out wearing scrubs, and he performs the abortion. He leaves, and the people who are there give me some pills to dry up my milk, and some maxi pads.

And then the guy drives me back to the movie theater on Eutaw Street. I stayed with a friend. I didn’t go back to my parents at night. That was it. At the time, I had a job working on the Hill for a Maryland congressman. And I was absolutely crazed that I had done this. I had done this illegal thing, and was that going to come back and — you know? But nobody ever found out about it.

Was I scared? I was terrified on the operating table. I couldn’t stop shaking. Would I have changed my mind? No, I would have driven off a bridge before I would have had a baby. I would have been forced into a marriage with a completely unsuitable human being.

By the end, I was on the pill. I can still hear the doctor that I then went to, who gave me the pill — that would have been later in 1966 — said to me, ‘Don’t let anybody in without a rubber.’

Yeah, too late. That’s why I’m here for the pill.

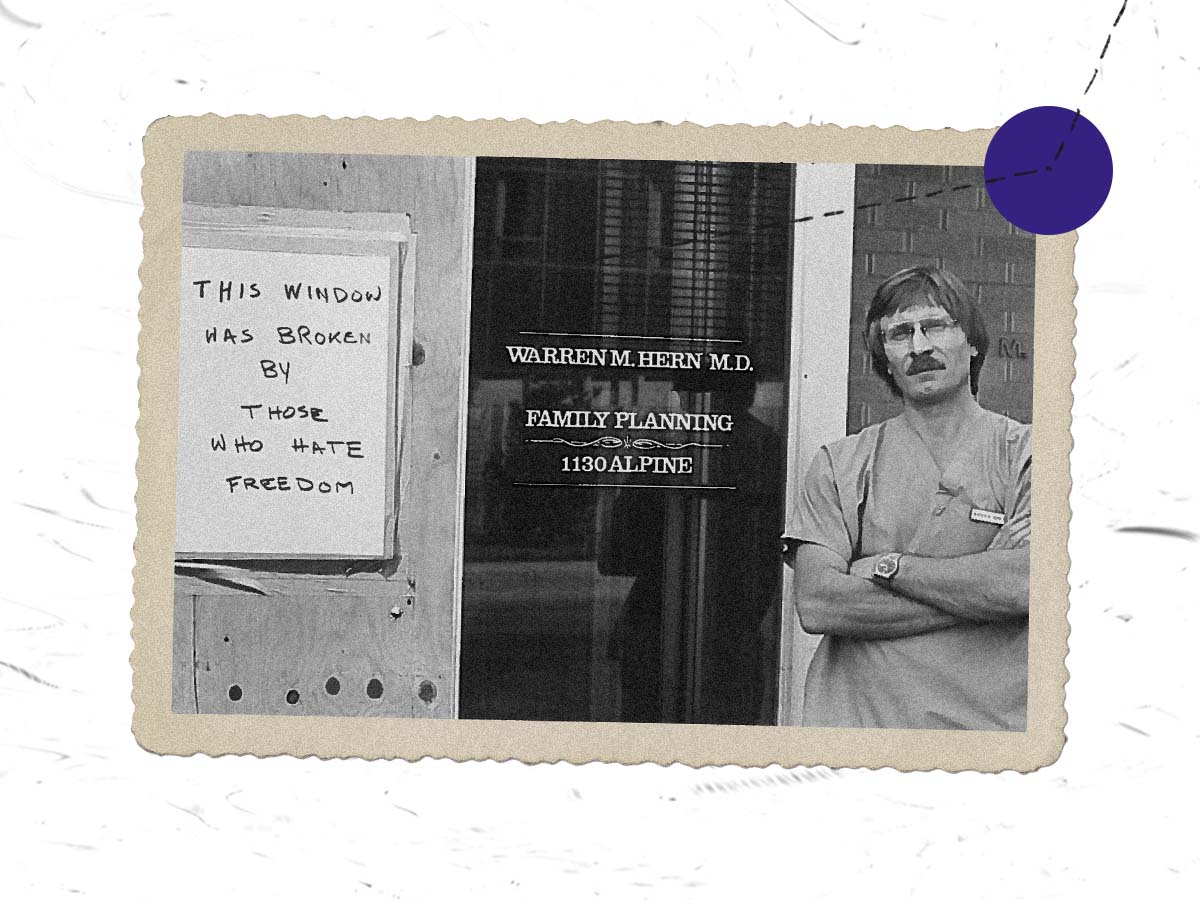

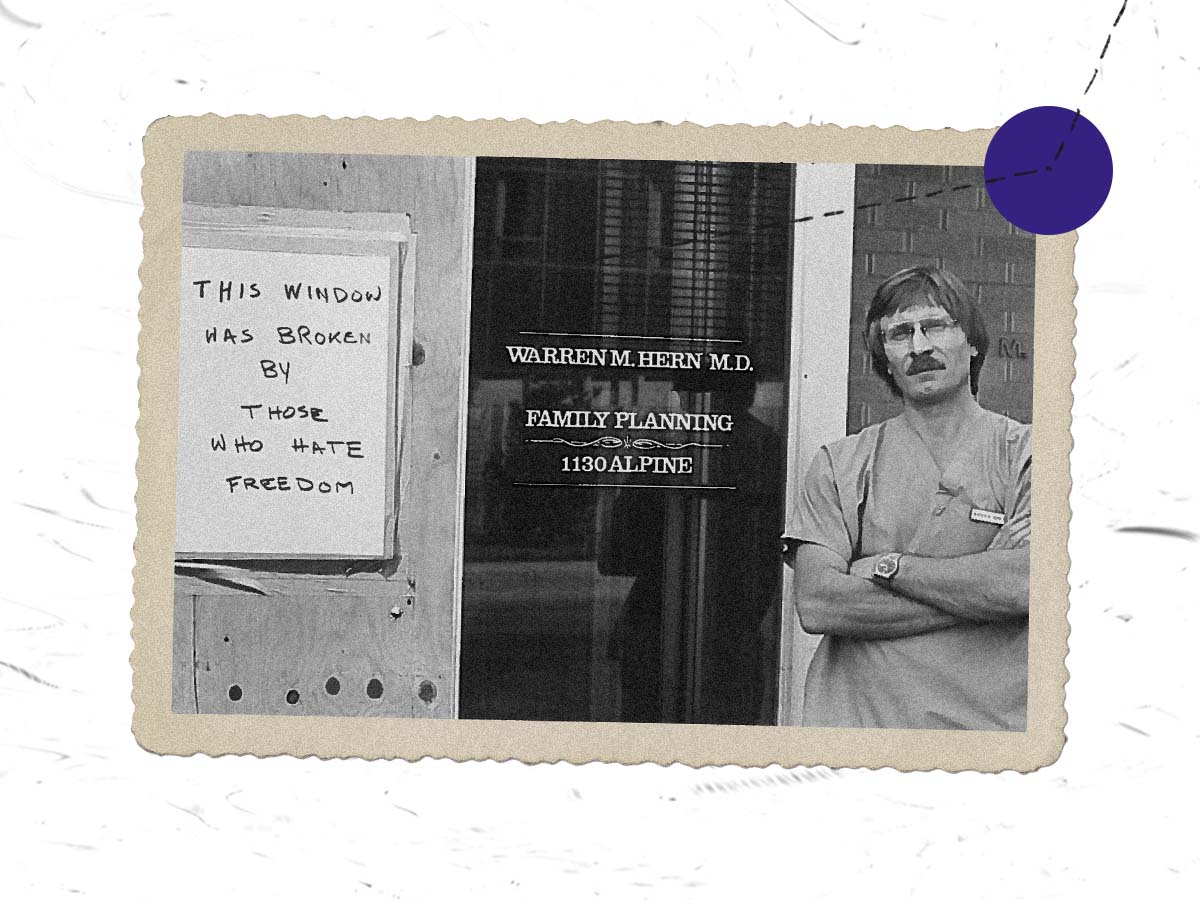

Warren Hern, 83, of Boulder, Colorado

Dr. Warren Hern standing in front of his medical practice. (Rena Li for The 19th)

Dr. Warren Hern standing in front of his medical practice. (Rena Li for The 19th)

I began to get acquainted with this issue when I was a junior medical student — this is back in 1963. Every night that I was on call in the gynecology ward, my colleagues and I were up all night taking care of the women who had either self-induced or poorly done illegal, unsafe abortions. I didn’t really understand it, to tell you the truth.

About that time, there was a woman who had gone to the emergency room to see if they could end the pregnancy. She was several months pregnant. When they refused, she went home and shot herself in the uterus and then drove to the hospital.

This is an example of the kind of catastrophic things that women did to themselves. They would put lye in their vagina to induce an abortion. They used coat hangers. They literally used coat hangers and knitting needles. They died. Some went to Mexico and sometimes they survived, and sometimes they didn’t. Women were desperate. And I think I saw this all the way through medical school. I saw it in Panama, at an internship. I saw it in Brazil in 1966 or 1968, when I was a visiting physician.

I was a visiting physician in Brazil for two years and I became acquainted with the doctors in the local maternity ward. They took me to the maternity ward. There was one ward full of women recovering from delivery, having a baby. There were two wards of women recovering from illegal abortion. Fifty percent of those women died. They were usually too sick to save by the time they got to the hospital. In Latin America, abortion was the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age.

I came back to the United States and I began studying public health. What I decided to work in was epidemiology — specifically population epidemiology — and that included looking at the health effects of illegal abortion.

It became clear to me that the effects of illegal abortion and the abortion laws were visited particularly upon women who were poor or many members of minority groups. The death rate due to illegal abortion was nine times higher among Black women than it was among White women.

Women were desperate.

I saw this across the country. When I was working in Washington, D.C., I was helping run a family planning program for the poor. We were taking care of several hundred thousand women across the country. And they were begging for abortion services and facilitation services.

I was in a preterm clinic in Washington, D.C., in 1971, and I learned how to do an early first-trimester abortion. I wasn’t really planning to practice medicine because I was recruited into epidemiology. But then I was in Colorado in 1973, when the Roe v. Wade decision came down. And I had been writing letters to the editor supporting this and pointing out how important this was for women, and for public health.

There was a group in Boulder that wanted to start a private nonprofit abortion clinic. And they got my name and called me and asked me if I would be willing to help them start this clinic. I had no intention of doing something like that. But when they invited me, I accepted the invitation, because I thought it was an important thing to do. Implementing the Roe v. Wade decision was extremely important. The decision itself didn’t get anybody an abortion; it was only meaningful if doctors were willing to perform the abortion.

We started performing abortions in November 1973. I immediately became the target of hatred by not only some anti-abortion people in the public, but members of medical community. I was subjected to a lot of abuse, and a lot of obscene death threats in the middle of the night. I was living up in the mountains in a cabin I got with my father, and I was very, very frightened. I expected to be assassinated anytime.

I love seeing patients and enjoy talking with them. And they tell me their stories. And every, every single one has an important story to tell.

Most of my patients now or at least at least half of them, sometimes more, are patients who have desired pregnancies that have a terrible complication of fetal disorder, genetic disorder. And they’ve decided to end the pregnancy, even though it’s a desired pregnancy. We see a lot of patients with those circumstances. We see patients who are extremely young, 11 and 12 years old, who’ve been raped or sexually abused. Victims of incest. These young girls should not have to carry a pregnancy to term. It’s very dangerous for them. They’re not prepared to be a parent.

But in any case, right now as we speak, we have anti-abortion fanatics in front of my office. There’s a man that comes and stalks me every Tuesday morning. And I think he wants to kill me. I have to assume that, because five of my medical colleagues have been assassinated.

Sara Toups at her home in New Orleans, Louisiana. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH)

Sara Toups at her home in New Orleans, Louisiana. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH) About two weeks after learning she was pregnant, Toups underwent noninvasive prenatal testing, which was recommended by her doctor and covered by health insurance since her age put her and the fetus at risk for other complications. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH)

About two weeks after learning she was pregnant, Toups underwent noninvasive prenatal testing, which was recommended by her doctor and covered by health insurance since her age put her and the fetus at risk for other complications. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH) Toups read countless stories about people who discovered problems later in their pregnancy who, because of abortion bans, couldn’t access medical care. She feared that if she discovered any complications, no doctor in Louisiana would be able to help her. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH)

Toups read countless stories about people who discovered problems later in their pregnancy who, because of abortion bans, couldn’t access medical care. She feared that if she discovered any complications, no doctor in Louisiana would be able to help her. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH) Toups tinkers with a mobile she and her partner installed above the baby’s crib. Toups was able to conceive without fertility treatment. But many people her age require those services to become pregnant. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH)

Toups tinkers with a mobile she and her partner installed above the baby’s crib. Toups was able to conceive without fertility treatment. But many people her age require those services to become pregnant. (CAMILLE FARRAH LENAIN FOR THE 19TH) (Rena Li for The 19th)

(Rena Li for The 19th) Lorraine Saulino-Klein, middle, in a photo from nursing school. (Rena Li for The 19th)

Lorraine Saulino-Klein, middle, in a photo from nursing school. (Rena Li for The 19th) Dr. Warren Hern standing in front of his medical practice. (Rena Li for The 19th)

Dr. Warren Hern standing in front of his medical practice. (Rena Li for The 19th)