Former solicitor general Neal Katyal and Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection chief Joshua Geltzer penned a column for The Atlantic explaining why Roger Stone shouldn't assume that he's free and clear after having his sentence commuted.

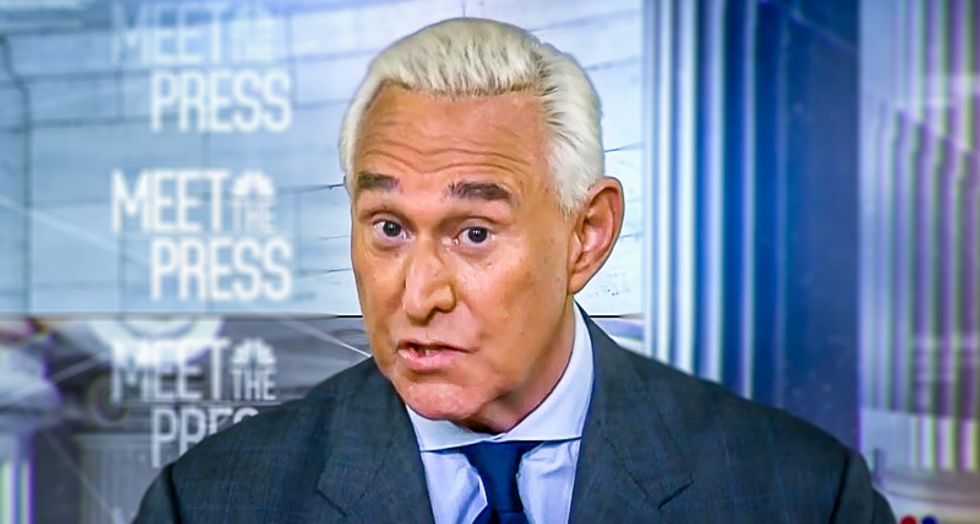

Stone, who was found guilty on seven felony counts by a jury last year, was supposed to report to prison on Tuesday, but his longtime friend, President Donald Trump, saved him.

The legal experts explained that Stone's commutation isn't indelible. Stone could be indicted by a future Justice Department.

"This fact highlights that on the ballot in 2020 is not just a forward-looking end to Trump’s corruption and lawlessness, but also a reversal of some of his administration’s worst excesses," wrote Katyal and Geltzer.

"Hours before the commutation, Stone said in an interview that he thought Trump would help him because the president 'knows I was under enormous pressure to turn on him. It would have eased my situation considerably. But I didn’t.' Stone thought that his silence would buy a permanent get-out-of-jail-free card from his friend. But, like everyone else who’s dealt with Trump, Stone got a raw deal," they wrote.

After bragging about withholding the goods on Trump, even if it would have "eased my situation considerably," Stone claimed he didn't withhold the goods on Trump in exchange for the commutation.

"Sure, Trump helped Stone by invoking his extraordinary constitutional powers to relieve Stone of the consequences of his 2019 conviction for lying to investigators, obstructing a congressional inquiry, and witness tampering. But Trump, characteristically, did as little as possible: He commuted Stone’s sentence but didn’t pardon him," Katyal and Geltzer wrote. "That means—as Special Counsel Robert Mueller wrote on Saturday—that Stone 'remains a convicted felon, and rightly so.' A commutation does nothing to erase or even call into question a convicted defendant’s guilt."

A future attorney general could open a new investigation into Stone's actions finding even more crimes. The jury in the Stone case even concluded that Stone could be guilty of other offenses.

"Stone was charged with (and convicted of) making false statements under the general false-statements law," the legal experts explained. "That law criminalizes false statements when made in the context of any 'matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch.' But another law specifically criminalizes 'cover[ing] up … any record' to impede a federal investigation. It appears Stone did just that, as his indictment alleges that he lied about no longer having emails and text messages that he did still possess. That could be the basis for a new charge—and it certainly provides a basis for a reopened investigation."

Similarly, Stone was charged and convicted of obstruction of Congress, which likely has links to committing other federal crimes like obstruction of justice. The redacted parts of Mueller's final report showed that former Trump campaign chair Paul Manafort revealed Stone knew the WikiLeaks were coming before they happened and that Stone told Trump they were forthcoming. Stone could be charged with aiding and abetting "the hack-and-dump that was the cornerstone of Russia’s interference."

Further, a future Justice Department would be able to garner further information because Trump administration officials who refused to cooperate wouldn't have the protection of a president's obstructions of justice.

"Finally, the commutation itself may be null and void if Trump carried it out to protect himself," wrote Katyal and Geltzer. They cited Stone's judge, Amy Berman Jackson, who said, Stone "was not prosecuted, as some have complained, for standing up for the president. He was prosecuted for covering up for the president."

"If the commutation itself was the product of nefarious activity, a future Justice Department may well conclude that Stone shouldn’t benefit from it," the piece said.

If Stone had been pardoned, judges may be unwilling to allow additional charges, but commuting a sentence "eradicates nothing of the guilt found by the jury," the editorial explained. The guilt isn't deleted, it just removes punishment for his conviction.

"Indeed, Stone’s conviction and commutation may supercharge another avenue: state prosecutions," the legal experts continued, citing Washington, D.C., Florida and New York as possible places for state crimes.

This isn't exactly a normal tactic, they explained, but they argued that these are not normal times.

"The president has commuted the sentence of a key witness against him, apparently to reward Stone for his silence. The majesty of the law is that it is supple enough to provide a remedy for this grave action," the piece closed. "Like many other times when Trump has shortchanged those he cuts deals with, Trump hasn’t actually protected Stone from further prosecution. If Stone wants to earn the finality he so obviously craves, he should try the same approach used by other convicted criminals: Come clean, and tell prosecutors what they want to know about the crimes in which he was involved."

Read the full editorial at The Atlantic.