Opinion

The few existing 'reasonable Republicans' could oust House Speaker John Boehner

House Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio addresses reporters at the Capitol, Oct. 10. House Republicans are still weighing a short-term debt-limit increase. Op-ed contributor Jeremy D. Mayer writes: This deal 'won’t eliminate the debate over spending…

Ignore the spin: This debt ceiling crisis is not just politics as usual

Never before has a minority party linked controversial legislative demands with a threat to shut down the government or imperil the global economy. But House Republicans would have you believe otherwise. In an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal this morning…

The only thing crazier than the shutdown is Fox News' coverage of it

Government shutdown theater has given us some surreal moments. Heard of the "trillion-dollar coin"? Obama actually mentioned it on Monday. It's a half-serious solution that some wonks have floated to solve the debt ceiling crisis, if "floated" is the right word for a coin that figures into most people's imagination as a giant, sweepstakes-style money cartoon.

Then there's Senator Ted Cruz reading children's books on the US Senate floor, a move that will undoubtedly give future historians and/or alien visitors curious ideas about the possible role of star-bellied sneetches (Cruz is a fan of Dr Seuss books) in our legislative process. Constant references to hostage-taking and suicide bombers will provide those same analysts with an exaggerated (though not by much) picture of gun violence in the early 21st century.

But you haven't witnessed the truly crazy until you turn on Fox News or browse the right-wing websites.

Here's a piece of absurdism you can appreciate right now: the image of a janus-faced conservative media talking head, with one mouth defiantly denouncing the impact of the government shutdown, and the other wailing at the costs of keeping government going. Sean Hannity, no great advocate of consistency anyway, has sputtered these two thoughts within minutes of each other. "The government is not totally shut down! Seventeen percent is it!" he told listeners Monday, before confiding that he believes the GOP will prevail, since "the public will side with the group that's willing to talk".

Laura Ingraham her listeners that she was "beginning to enjoy" the shutdown; she also tweeted out her apparently earnest concern that the closure of a parking lot on federal land meant that "ppl risk their lives pulling off the GW Pkwy".

Fox News has been a funhouse of these distorted twin thoughts, not surprisingly, with guest after guest mocking the seriousness of the shutdown; in a particularly Orwellian stroke, someone at the network even did a search-and-replace on AP stories run on the site, replacing "shutdown" with "slimdown". At the same time, they've given breathless coverage to a highly-selective pool of "slimdown" victims: first, the second world war veterans who faced some inconvenience at the war's memorial, and, more recently privately-funded parks and – incorrectly – the nation's missing-child "Amber Alert" system.

Let's unpack this rhetoric, since it's wholly representative of the coverage that conservative media has given the shutdown. With one side of your head, you need to remember that government is bad, and that the less of it there is, the better. Supporting that thought is the belief that a government "slimdown" won't disrupt any of the government's more important functions.

With the other side of your head, you need to dredge up righteous indignation at the loss of some government functions. It almost doesn't matter which ones, though it's helpful if they are services that strike a sympathetic chord without being, you know, necessary. The right-wing Washington Examiner has some examples to get you started, including "Lake Mead, NV property owners" and "tourists".

Now, try to stand up. Do you feel a little dizzy? Seeing double? You better sit back down.

How is it that so many conservatives seem able to not just stand, but stand for hours and hours and hours holding both these thoughts in their heads? It would be easy to dismiss them as cynics, that perhaps they don't believe either proposition. But as the remarks about "being willing to compromise" caught on a hot mic between Republican Senators Rand Paul and Mitch McConnell show, at least some of their convictions are sincere – maybe especially this part, "I know we don't want to be here, but we're gonna win this, I think."

Conservatives' problem is not so much that these are two ideas with no basis in fact, but that both ideas have some basis in fact.

That government is unpopular is the easy part. There's a long and even somewhat honorable history to that tenet of conservative philosophy. In fact, that's pretty much argument that the leaders of the shutdown strategy made over the summer to skeptical lawmakers and not-so-skeptical Tea Party activists.

There is one important difference between the small-government philosophy as espoused by, say, the Anti-Federalist Papers and the arguments made by the Tea Party Patriots and Heritage Action: the anti-federalists argued from logic, these modern-day PACs used a misleading poll. They asked voters in conservative districts if, "in order to get … Obama to agree to at least have a 'time out'" before implementing the Affordable Care Act, "would you approve or disapprove of a temporary slowdown in non-essential federal government operations, which still left all essential government services running?"

Well, if you put it that way … And, of course, they did put it that way, and found that voters supported a totally painless shutdown by a 2-to-1 margin.

And this gets us to the half-truth behind the outrage at "slimdown targets": however much you dislike the faceless bureaucracy of "the government", there are very few people who truly want to live without the services it provides. The traditional basis for party divisions has been in deciding what services it provides, and to whom. It makes us hypocrites; it makes us human. Most of us don't really try to argue two different philosophies at the same time, we cave to realism and sentiment. We agree to feed the children of poor families and pay for safety regulations to be enforced. We haggle over the small things because sometimes the big ideas are too large to be contained in a single debate, and it's foolish to even try.

F Scott Fitzgerald once called "hold[ing] two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain[ing] the ability to function" the "test of a first-rate intelligence", but when it comes to the GOP, the jury's out on the "functioning" part.

Are Americans dumb? No, it's the inequality, stupid

Are Americans dumb? This is a question that has been debated by philosophers, begrudging foreigners and late night TV talk show hosts for decades. Anyone who has ever watched the Tonight Show's "Jaywalking" segment in which host Jay Leno stops random passersby and asks them rudimentary questions like "What is Julius Caesar famous for?" (Answer: "Um, is it the salad?") might already have made their minds up on this issue. But for those of you who prefer to reserve judgement until definitive proof is on hand, then I'm afraid I have some depressing news. America does indeed have a problem in the smarts department and it appears to be getting worse, not better.

On Tuesday, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released the results of a two-year study in which thousands of adults in 23 countries were tested for their skills in literacy, basic math and technology. The US fared badly in all three fields, ranking somewhere in the middle for literacy but way down at the bottom for technology and math.

This shouldn't be all that surprising as there is a well documented pattern of American school kids failing to keep up with their tiger cub counterparts in other countries. But these results are the first concrete proof that this skill gap is extending well beyond school and into adulthood. The question is, do the study's results imply, as the New York Post so delicately put it, that "US adults are dumber than your average human"? Hardly, but it does suggest that many Americans may not be putting the smarts they have to good use, or, more likely, that they are not getting the opportunity to do so. Put another way: it's inequality, stupid.

Just a quick scan of the countries that fared really well in all three categories (Norway, Sweden, Japan, Finland and the Netherlands) compared to the countries that fared really badly (America and Britain) gives a pretty good indication that the inequality that is rampant in the (allegedly) dumber nations might have something to do with their pitifully low scores. A closer look at the results is also revealing. The incomes of Americans who scored the highest on literacy tests are on average 60% higher than the incomes of Americans with the lowest literacy scores, who were also twice as likely to be unemployed. So broadly speaking, the better off the American, the better they did on the tests.

Now this is just a wild guess, but could this possibly have something to do with the fact that the kind of schools a poor American kid will have access to are likely to be significantly inferior to the kinds of schools wealthier kids get to attend? Or that because of this, a poor kid's chances of getting into a good university, even if she could manage to pay for it, are also severely compromised? And let me go one step further and suggest that the apparent acceleration of America's dumbing down might be directly connected with the country's rising poverty rates.

Before I go on, I should say that even I can see some holes in the above theory. You only have to look at certain members of congress (read Republicans who forced the government to shutdown last week), for instance, many of whom attended some of the finest universities (and make bucket loads of money), to see that even an Ivy League education may be of little use to a person who is simply prone to stupidity. I should add also that many people believe that it's the large immigrant population (of which I'm a member) who are responsible for bringing down the nation's IQ, which further complicates the dumb American narrative. Indeed one could argue all day about the reasons Americans are falling behind, (Woody Allen blames fast food), but we should at least be able to agree on the remedies.

Here's the thing, most economists agree that in this technology driven age, a highly skilled workforce is key to any real economic recovery. It doesn't bode well for the future then that so many American students, particularly low-income and minority students, are graduating high school without basic reading or math skills. Nor does it inspire confidence that students who leave school without basic skills are not acquiring them as adults. So America's alleged dumbness has a lot to do with inadequate schooling for (poor) children and teenagers and a dearth of continuing education opportunities for low-income adults. By contrast, the OECD study found that in (more equal) countries that fared better in the tests, like Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands, more than 60% of the adult population have engaged in continuing education programs or on the job training.

The smart thing to do then surely would be to pour resources into early and continuing education opportunities so that American adults will be equipped with the necessary skills to compete in the global economy. This is where the dumb argument really gets a boost, however, because the opposite is happening. Those same congressional geniuses I alluded to earlier are also responsible for forcing through the cuts known as sequestration, which among other things cut 5% from the federal education budget. Because federal education funding is doled out according to the number of low-income students in a given school, it is poor children, the ones who most need the help, who are being disproportionately impacted by the cuts. Furthermore since 2010, almost $65m, over one-tenth of the entire budget, has been cut from adult education grants.

So are Americans dumb? The answer appears to be yes, some are. The dumb ones are not the poor minorities or low skilled adults who fared badly on the OECD tests, however, but a certain privileged and selfish elite, who have suffered from no want of opportunities themselves, yet seem to think that denying millions of struggling Americans an equal (or indeed any) opportunity to get ahead is a sensible way forward. The results are in now and clearly it isn't. The question is will enough Americans be smart enough to do something about it?

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2013

["Stock Photo: Confused Man Scratching Head" on Shutterstock]

'Breaking Bad' can't be art: Thoughts on the first truly naturalist television narrative

A few weeks after the finale of Lost, Chad Post attempted to defend it by claiming that its nonsense was the stuff of art. "What’s interesting," he argued, "is how these six seasons functioned as ... a great work of art [that] leaves things open to interpretation, poses questions that go unanswered, creates patterns that are maybe meaningful." I'm not interested in discussing the merits of the Lost finale – whether all of the "survivors" Oceanic 815 were dead the entire time or some of them were only dead most of time doesn't matter, as they're both the narrative equivalent of convincing a child you've stolen its nose: it only works because kid's not equipped to know it doesn't.

Defenders of the Lost finale, of course, have no such excuse and are instead forced, like Post, to recapitulate aesthetic theories they half-remember from high school – in this case, the quasi-New Critical theory that elevates the interpreter over the work of art. It's the critic, after all, not the artist, who benefits from "leav[ing] things open to interpretation."

The New Critic was an archeologist of ambiguity, teasing from every contradiction he encountered a paean to the antebellum South. They valued ambiguity as an aesthetic virtue because poems and novels that possessed it could be made to be about anything, which freed them to make statements like, when it came to great works of art, "all tend[ed] to support a Southern way of life against what may be called the American or prevailing way." And they did so by being ambiguous, which allowed the New Critics to say, without irony, that great works of art celebrated "the culture of the soil" in the South. This, dear reader, is the brand of literary and aesthetic theory you were likely taught in high school, and by its druthers, Breaking Bad's not even a work of art, much less a great one.*

In fact, by this standard, it's quite possibly the least artful narrative in the history of American television, and because of this, it's the first show that deserves the label "naturalist." The naturalist novels of the early 20th Century were tendentious in the most base sense of the word: any tendency that appears in characters' personality early in a book will, by its end, have metastasized into impulses so vast and deep you wonder why they even tried to repress them.

For example, in the first chapter of McTeague (1899), Frank Norris compares his titular character to a single-minded "draught horse, immensely strong, stupid, docile, obedient," whose one "dream [was] to have projecting from the corner window [of his "Dental Parlors"] a huge gilded tooth, a molar with enormous prongs, something gorgeous and attractive."

There's your premise: McTeague is dumb and stubborn, especially in the service of his vanity. In the next chapter, when he tries to extract a tooth from the mouth of a patient he's fallen in love with, it's no surprise that "as she lay there, unconscious and helpless, very pretty [and] absolutely without defense ... the animal in [McTeague] stirred and woke; the evil instincts that in him were so close to the surface leaped to life, shouting and clamoring."

"No, by God! No, by God!" he shouts, then adds "No, by God! No, by God!" He tries not to sexually assault her, but fails, "kiss[ing] her, grossly, full on the mouth." Moreover, his failure revealed that "the brute was there [and] from now on he would feel its presence continually; would feel it tugging at its chain, watching its opportunity." When the woman, named Trina, wakes from the procedure, he proposes to her with the same stupid vehemence with which he tried not to assault her:

"Will you? Will you?" said McTeague. "Say, Miss Trina, will you?""What is it? What do you mean?" she cried, confusedly, her words muffled beneath the rubber.

"Will you?" repeated McTeague.

"No, no," she cried, terrified. Then, as she exclaimed, "Oh, I am sick," was suddenly taken with a fit of vomiting.

One of the most prominent features of naturalist prose, as you can see, is stupid, ineffective repetition in the face of adversity. McTeague can shout "No, by God!" as many times as he'd like, but he still assaults her, and no matter how many times Trina says "No, no" in response to his "Will you?" the only way this ends well for either of them is if she vomits all over his office. Given such favorable initial conditions, would it surprise you to learn that after she wins the lottery, he beats her to death? Or that the novel ends with him handcuffed to the dead body of his best friend, who he also beat to death, in Death Valley?

Because McTeague is a naturalist novel, it shouldn't. The key phrase buried in the previous paragraph is "initial conditions," because when you're in the presence of a naturalist narrative, they're all that matter.

By now, I'm sure it's obvious how this relates to Breaking Bad: in a real sense, the second through fifth seasons mark the inevitable, inexorable consequences of what happens when someone with Walter White's character flaws is put in the situation he's put in. Like his forbear McTeague, he's incapable of developing as a character: he can only more robustly embody the worst aspects of his fully-formed personality.

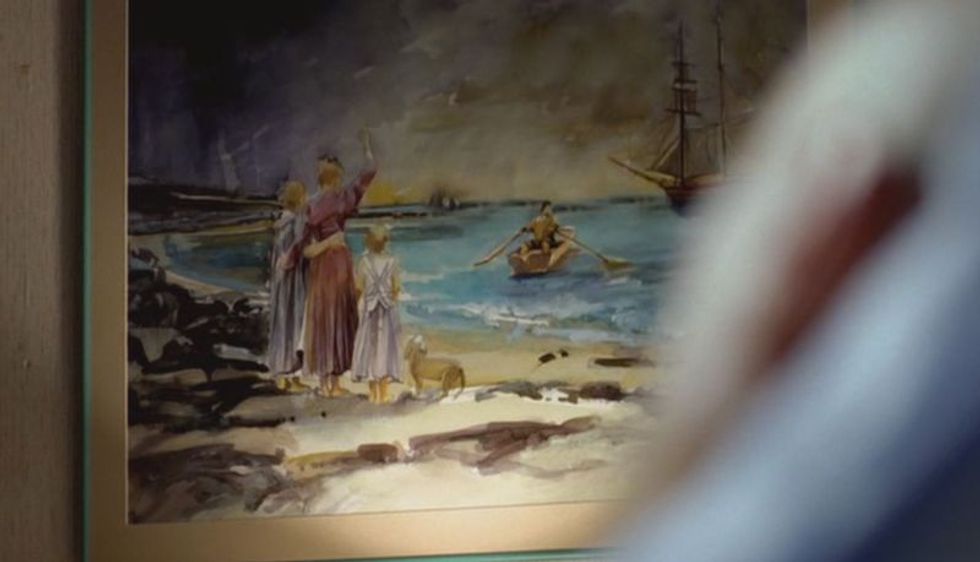

This is why, in naturalist novels and Breaking Bad, repetition is so significant: it's only when provided with a reminder of where the narrative started that we're able to recognize how much the central character hasn't changed. Every time we see another visual echo from episodes past – and in the fifth season, they come fast and frequently – we're reminded of how committed Walter is to his vision of himself as a heroic figure struggling against a universe determined to wrong him. Consider this shot from "Bit by a Dead Bee," the third episode of the second season:

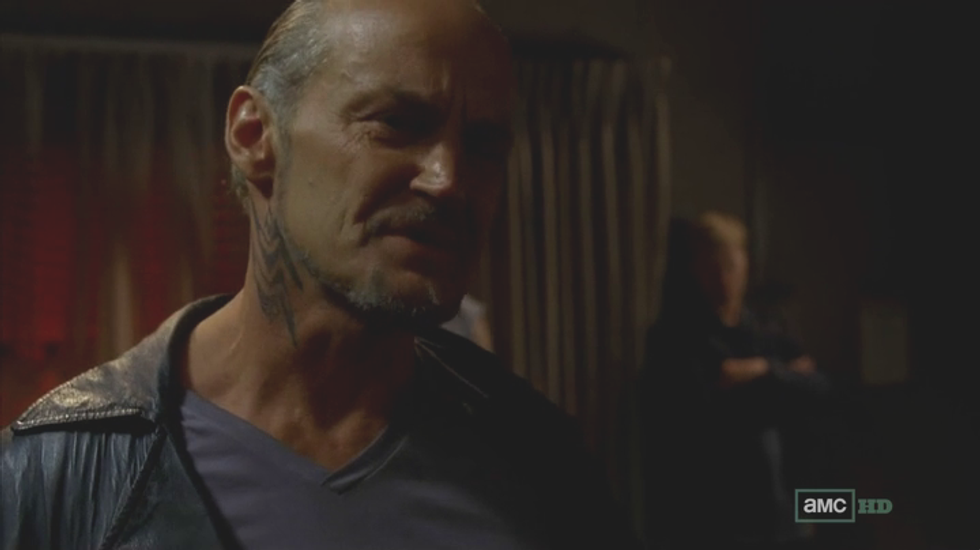

Walter is in his hospital bed after the shoot-out with Tuco in the desert, which happened after he had been missing for three days and, of course, which almost got his brother-in-law Hank killed. He's also claiming that the cancer treatment ate the memory of the walkabout it sent him on. The difference between the man he is – one who's capable of devising a cover story for his meth-related absence that involves playing cancer for sympathy – and the one he imagines himself to be: the one in the boat, about to leave his family alone, possibly defenseless, while he heroically sets out into the great unknown. The next time he sees that image, he's in a motel room surrounded by white supremacists planning the coordinated execution of the remainder of Gus's crew. The director of “Gliding Over All,” Michelle MacLaren, moves our eyes around the scene before settling on a convoluted long shot:

MacLaren is fond of shots in which you're forced to follow eyelines around the frame in order to make sense of the scene, and like that banquet in the “Second Sons” episode of Game of Thrones, it's only after you've done the work of following everyone's eyes around the room that you realize that the most important element in the frame isn't actually in the frame. Once you follow an eyeline to an uninteresting terminus, you move on to the next character, so if you start analyzing the frame from the center and track on action, you'll move to Kenny stretching and follow his eyes (red) to the floor, then Frankie shuffles in place, so you look at him and follow his eyes (blue) to the table, but since that seems unpromising, Todd catches your attention when he shifts his weight, then you follow his eyes (green) to the bed, which means that McClaren's direction has compelled you to move your eyes around the screen until you reach the area of the bed at which Todd's staring, which is puts them right next to Walter, who has remained stock-still throughout. She didn't need him to move or even speak to draw your attention to Walter, she's done so by other means. Once she has you where she wants you, she has you follow his eyeline (yellow) to its terminus, which is off-frame.

Following eyelines to their rainbow's end is a function of film that doesn't necessarily pique our curiosity, but when we come to the end of our journey around the frame and the most significant character in it is staring at something off it, we desperately want to know what he's looking at.** McClaren knows that we'll be less interested in the frame when we find out what he's staring at, so beginning with that long shot (14:43), she cuts to a medium close-up on Jack (15:06), a close-up on Kenny (15:10), a medium shot on Todd (15:13), an extreme close-up on Jack (15:17) that racks to a medium shot on Frankie (15:20) before reversing to the initial medium on Jack (15:23), then back to the initial medium close-up on Jack (15:24) before jumping to a clean medium on Frankie (15:28), then to a more extreme close-up on Jack taking a drag (15:29), then she moves back to the close-up on Kenny (15:31), then back to Jack (15:35), back to Kenny (15:39), and back to Jack (15:41) until finally returning to Walter (15:50), who is of course still staring at something off-frame. McClaren's refused to provide us with the information we desire for more than a minute at this point, but it wasn't a typical minute.

According to the Cinemetics database, the average shot length (ASL) in “Gliding Over All” is 5.8 seconds, but as you can see from above, after that initial 23-second-long shot of Jack, the scene has an ASL of 3.8 seconds.*** Lest you think I'm using the kind of “homer math” that leads sports reporters to write about how their team's ace has the best in ERA in the league if you throw away the four starts in which he got rocked: I'm sequestering this bit of the scene and treating its ASL in isolation because we watch scenes sequentially and in context.

The shift in the pacing of editing created the impression that something really exciting was happening, but “four guys in a motel room talking about doing something exciting” actually qualifies as exciting; the other alternative is that the shot-frequency accelerated because McClaren was building up to something exciting, like the revelation of what Walter is staring at. The editing could be doubling down on the anticipation created by that intial long shot: as frustrating as it is to watch shot after shot fly by without learning what's on that wall, the editing's at least affirming our initial interest in it.

Or was, until she cut to the close-up of Walter staring at the painting (15:50), and because it's a close-up of someone staring at something off-frame, you assume that the next shot will be an eyeline match, but no, MacLaren cuts back to Jack, who's explaining to Walter how murdering ten people is “doable,” but murdering them within a two minute time-frame isn't. In a typical shot/reverse shot situation, especially when it's in the conversational mode as this one is, you expect the eyelines to meet at corresponding locations in successive frames. If Walter's head is on the right side of the frame, and it is, you expect Jack to be looking to the left side of the frame in the reverse, and he does:

The sequence is off-putting because Walter's violating cinematic convention in a way that makes us, as social animals, uncomfortable. On some fundamental level, the refusal to make eye contact is an affront to a person's humanity, so even though Jack's a white supremacist with a penchant for ultra-violence, we feel a little sorry for him. He is, after all, being ignored in favor of we-don't-even-know-yet, but at least it's something significant. MacLaren wouldn't have put all this effort into stoking our interest in something of no consequence, but that doesn't mean we're thrilled when she cuts out to the initial long shot in which whatever-it-is remains off-frame, or when she cuts to an odd reverse on Walter, who asks “Where do you suppose these come from?”

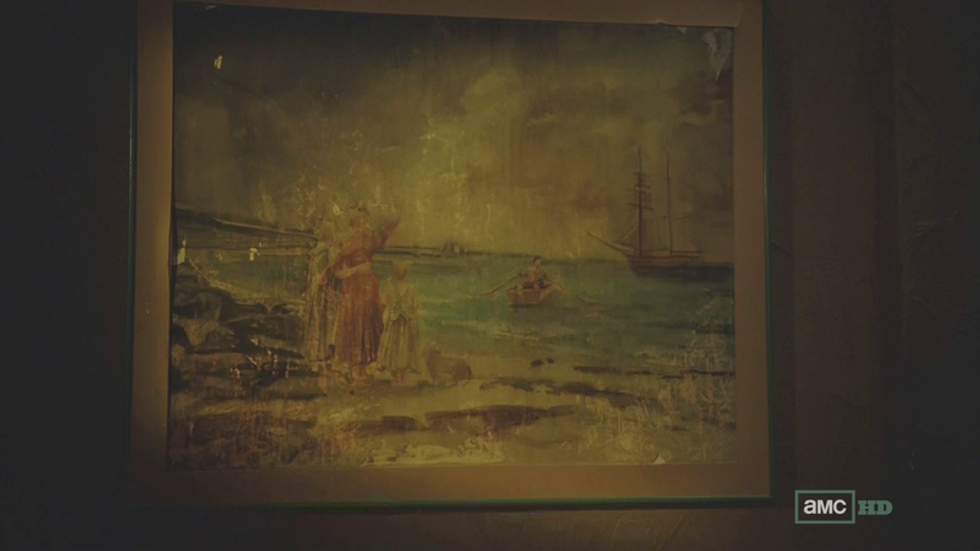

How wonderful is that “these”? We're finally going to learn what Walter's been staring at, but even the dialogue is militating against our interest, providing us with the pronoun when all we want to see is the antecedent. MacLaren holds on Walter for one last agonizing beat before finally reversing to this image of the painting (16:09):

This reverse shot seems more conversational than the last – again, in a way that insults Jack's essential humanity, or whatever passes for it among white supremacists – only now the conversation isn't between Walter and any of the actual human beings sharing that motel room with him, it's with himself.****

“I've seen this one before,” he informs the very people he just insulted. It's not that he's wrong – it is the same painting he saw after he ended up in the hospital, and the timing here is crucial. In “Bit by a Dead Bee,” his outlandish plan had just been successfully completed, so when he looked at the husband heroically rowing out to sea, nobly sacrificing himself for the family he's left behind, he sympathetically identified with a man who shared his current plight, who had made a decision and was following through with it for the sake of those he loved. But in “Gliding Over All,” he sees the same painting before one of his outlandish plans has come to fruition, so now when he sympathizes with the husband heroically rowing out to sea, nobly sacrificing himself for the family he's left behind, he identifies with him because they share a common fate, as both have to decide whether to continue with their foolishness or return to shore.*****

Astute readers may have noticed that I just wrote the same sentence with different words. That's because I did. The only “development” Walter's underwent from the first time he saw that painting to now is that he's more fanatically committed to the image of himself as the hero sacrificing himself for his family. Every sacrifice he makes on his family's behalf only makes him more of the same same kind of hero he's always imagined himself to be.

The presence of this painting – as well as the other visual echoes, most obviously Walter's birthday bacon – reminds us that it's only been eleven months since the moment he first saw it, in November 2009, to the moment he sees it in “Gliding Over All,” in October 2010. Naturalist novels also focused on the rapidity with which can descend in the absence of a social safety net. McTeague's life unravels astonishingly quickly once he loses his job: four months later he and Trina are living in squalor; a month after that, she moves into an elementary school; two months later, he murders her; two months after that, he's chained to the body of a dead man in the middle of Death Valley. Because of the kind of person he is, this is how McTeague's life had to end. Aaron Paul's appearance in Saturday Night Live demonstrates just how much Breaking Bad shares this naturalist concern.

I could go on: the short stories and novels of Jack London were about the opportunities to be had in the wilderness, and the dangers associated with them. In his most famous story, “To Build a Fire,” there is a moment in the fourth paragraph when the nameless protagonist could have, and should have, turned back. Once he makes the decision not to, his fate is sealed, it just takes another 40,000 words to reach it. If there's an art to enjoying a man struggle in vain against his inevitable doom, it's been lost to us – or had been, until Breaking Bad, which demonstrated that there is an audience for naturalist narratives, bleak and unremitting though they may be. Moreover, the opening scene of the finale, “Felina,” almost seems like a combination of “To Build a Fire” and another famous naturalist story, Ambrose Bierce's “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” I'm not saying I believe that Walter dreamed he took his revenge in the moments before he froze to death, but it's not entirely implausible, especially if the series is considered in the light I've presented it here. (Norm MacDonald, of all people, has my back on this.)

The question remains, then, whether Breaking Bad qualifies as "art." Literary naturalism's reputation has faded since the 1930s because, in part, critics consider it more akin to an experiment than literature. Literature requires its characters to develop, to become "round," as they used to say -- whereas naturalists were like scientists who would rather take a personality type and stick it in fifteen different environments so they could observe its behavior. When you consider the conversations that followed George R.R. Martin's comment about Walter being a bigger monster than anyone in Game of Thrones, you can see where that temptation comes from, and how powerful it is, three-thousand comments deep in discussions about whether White would've been more like Tywin Lanister or Roose Bolton.

So is Breaking Bad art? Of course it is. The absurd amount of detail included above isn't meant to overwhelm, merely to acknowledge the level of artistry that went into demonstrating that Walter hasn't grown. I would take it one step further and say that even if you don't believe naturalist narratives can be considered "art," Breaking Bad would still be art, because as much as critics focus on the show's content, what separates it from most television is the manner in which it's presented. Even if the plot itself were terrible, the manner in which it's shot would elevate it to the status of art.

*The main reason New Criticism was adopted as a model was that, unlike the modes of historicism that preceded it, it was infinitely scalable. After the GI Bill was passed, even college and university faculty were worried that their students lacked the educational background required to write the kind of research papers they'd previously assigned, but anyone could be a New Critic: all you had to do was look at a poem and point out what didn't make sense, because that's what it a work of art. Within half a decade, the bug of student ignorance became a feature.

**If you were paying close attention when the scene opened, you would've noticed, since she opens with a medium shot of the painting, then pulling back and sweeping to the right. Like many scenes in Breaking Bad, this one is sequenced backwards, providing us with information before we can understand – or if you've seen “Bit by a Dead Bee” recently, remember – the significance of it.

***For the record: 4 seconds, 3 seconds, 4 seconds, 3 seconds, 3 seconds, 1 second, 4 seconds, 1 second, 2 seconds, 3 seconds, 4 seconds, 4 seconds, 2 seconds, 4 seconds, 4 seconds, 2 seconds, and finally 9 seconds.

****Before you wonder why I'm not just calling that an eyeline match, because it's also one of those, keep in mind that not only has Walter been staring at it with a faraway look in his eyes for almost two-and-a-half minutes, he now appears to be asking it a question. Also, in a move seemingly designed to frustrate my former students, check out the examples the Yale Film Analysis site chooses for “eyeline match” and “shot/reverse shot.

*****The boat seems closer to shore than ship, after all, which only adds to the nobility of the man rowing it out to sea, because it'd be so much easier to just turn around.

[This was originally published at Lawyers, Guns & Money, where Scott Kaufman also writes when he's not chairing the AV Club's Internet Film School.]

'Breaking Bad': A Tragic Gay Love Story

Sunday night's Breaking Bad finale was incredible. It was the first time my sympathy for Walter White outweighed my anger toward him. I teared up when I saw him talk to Skylar for the last time, look at his daughter for the last time and see his son for the last time. And I got really verklempt when Walt rescued his side-kick in distress, freeing Jesse from the clutches of the Aryan Brotherhood, by throwing him to the ground and protecting him the hail of bullets that would ultimately kill everyone except Jesse. How romantic! This is hardly the only scene that lends itself to a homoerotic reading of Breaking Bad. Ladies and gentleman, I present "Breaking Bad: A Tragic Gay Love Story."

Why I hate Bridget Jones

Help, Bridget's back. She's a widow but she's as vapid, consumerist and self-obsessed as ever. I don't buy this anti-feminist fiction

Calories consumed: No idea. Alcohol units: None of your business. Shisha pipes: Only 2! I am so on trend. Murdered main character: Just the one.

Bridget Jones is back. Get out the big knickers and cocktail shaker. She is now more espresso martini than chardonnay. For Bridget is everywoman, after all, isn't she? Obsessed with three of the most boring things in the entire world: dieting, trying to get a bloke and drinking and feeling bad about it. I thought she had been put out of her misery by marriage but now she is a widow. Well, at least we have bypassed the smug married phase and we can go straight back into looking for lurve. That, dear reader, is Bridget's raison d'etre, for this is what romance, romcoms or chick lit has to do.

Helen Fielding is a brilliant social observer and preceded the shopping and fucking of Sex and the City by years. She zeited the geist of the mid-90s superbly, but Bridget, never trying be too strident (offputting to men) was for me the epitome of post-feminism – vapid, consumerist and self-obsessed. Bridget's much-vaunted independence, gained on the back of the feminism of the previous two decades, manifested chiefly as the freedom to get pissed, appreciate her female friends and speak openly of her sexual desires. For that we may be grateful? Many women clearly identified with this.

In 2013 Bridget is a single mum with two kids, she has discovered nits – what took her so long? – and thigh-high boots. Probably the result of the 5:2 diet but I couldn't care less. The point is that whatever Bridget thinks of herself we must know she is desirable. And lo, she has "a toyboy".

Who is Fielding writing for now? I am her age, and I can't work it out. It may be heresy but I just never identified with her heroine in any way. The ditziness, the choice between the good man and the bad boy (Darcy and Cleaver), the overbearing parents all seemed infantilising. As for having kids, I just thought get on with it. Now she is alone again and the internet has been invented, she could have sex any time. But Bridget doesn't just want sex, does she?

Obviously Darcy had to be killed off even if the fans are upset, because this character is based on lack. The lack of a man. Lack and guilt. Bridget at 51 is more cynical, but without this quest what would her life be? Lunches, Ocado deliveries, chauffeuring children to extra-curricular activities ?

This, you may say, simply reflects real, if real life means you don't have to earn money. Especially in the movies, the aspirations and class assumptions are not hidden. Clearly, though, the identification with Bridget is the one pimped by so much media aimed at women: self-improvement as self-empowerment. Self is the key word. Go girl, at a time when women actually have less and less.

Of course Bridget can make me laugh but her confusion didn't. Still doesn't. The humour that comes from her rhetoric about being a strong independent woman is always undermined by her pseudo neurosis – waiting for the man to ring or, now she has discovered social media, to ping.

What fills the lack is self-indulgence. The promise of post-feminism after all was some Manolo Blahniks, a Mr Big or Darcy, some cracking sex toys, boozy nights out with the girls. And shopping. In the end, liberation is reduced to libido. Hey, I've still got it and hey, I am certainly worth it.

Poor Ms Jones, still hiding her cleverness, putting up with crap from Cleaver and worrying about the competitive school run. Sorry, I am not buying this fiction. The fiction is that post-feminism is not in fact anti-feminism.

It is.

The fiction is that self-obsession is funny because collective struggles are a thing of the past. But this is Bridget Jones, not Emma Goldman. It's not my bag. And guess what? I don't feel guilty about this in any way.

Hollywood copyright cartel's plot to indoctrinate California kindergartens

Sharing is the essence of digital creativity, but its enemies want to brainwash grade-schoolers with their commercial interests

In kindergarten, we teach children to share. By second grade – if people who bring you songs and pixie dust have their way – we'll amend that in a major way.

Hollywood and the recording industry (aka the Copyright Cartel) are leading the charge to create grade school lessons that – at least, in their draft form, as published by Wired – have a no-compromise message: if someone else created it, you need permission to use it.

Sounds wonderful, until you think about how creativity actually works. And never mind that the law, already tipped in favor of copyright holders, doesn't hold such an absolutist position.

It's no surprise to learn that America's biggest internet service providers – let's call them the Telecom Cartel, since that's what they've become – are part of this propaganda scheme. It's sad to learn, however, that the California School Library Association has climbed aboard; the organization helped produce the lessons that, thankfully, are still only in draft form. But they are likely to reach California classrooms later this school year and, presumably, other parts of the nation later on.

Wired obtained some of the draft lesson plans. They're amazing (and not in a complimentary way). The lesson aimed at second graders (pdf), for example, winds up this way:

We are all creators at some level. We hope others will respect our work and follow what we decide to allow with our photos, art, movies, etc. And we 'play fair' with their work too. We are careful to acknowledge the work of authors and creators and respect their ownership. We recognize that it's hard work to produce something, and we want to get paid for our work.

We're definitely all becoming creators, and we do want others to respect our work. But in the real world, and under the law, we can't make all the decisions about what uses we allow of that work. There's a concept called "fair use" – deliberately ignored in the lesson, on the absurd basis that kids can't understand it – that explicitly allows others to make use of our work in ways we don't like, or anticipate. Without fair use, creative works would be next to impossible, because we all build on the work of those who came before us.

Needless to say, this lesson and others made public – including grades one (pdf), five (pdf), and six (pdf) – have sparked a bit of an uproar outside the cartel's orbit. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Mitch Stoltz told Wired:

[The material] suggests, falsely, that ideas are property and that building on others' ideas always requires permission. The overriding message of this curriculum is that students' time should be consumed not in creating but in worrying about their impact on corporate profits.

What should schools actually be teaching? Happily, there are alternatives honoring copyright, which is important, but that also honor tradition, law and the greater culture.

Creative Commons' Jane Park has compiled an excellent listing of resources that educators can use to teach about copyright. I'm especially partial to the EFF's Teaching Copyright, which I've recommended to students of all ages, including some college students.

The California School Library Association should never have let itself become a handmaiden to commercial Hollywood. Perhaps, its leaders will realize that they are undermining the crucial role libraries have played in our society when they assist the copyright absolutists' agenda – because if libraries were invented today, the cartel would declare them to be both illegal and immoral.

I take some solace in a quote of the association's vice president, Glenn Warren, in the Wired story. Confronted with the inaccuracy and imbalance of the lessons, he acknowledged:

We've got some editing to do.

© Guardian News and Media 2013

[Portrait of a cute cheerful girl with painted hands, isolated over white via Shutterstock.com]

The willful idiocy of alleged 'global temperature decline' is based on a mirage

The landmark new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is crystal clear: human action is warming the planet and we're heading for big trouble if carbon emissions are not slashed. As Prof Tim Palmer, at the University of Oxford put it: "The report is further reinforcement that there is an unequivocal risk of dangerous climate change."

Yet before the ink is even dry critics are trying to obscure this stark message behind a mirage: the supposed halt in global warming over the last 15 years. This willful idiocy is based on the fact that air temperatures at the Earth's surface have more or less plateaued since the record hot year in 1998.

What critics choose to ignore is that of all the extra heat being trapped by our greenhouse gas emissions - equivalent to four Hiroshima nuclear bombs every second - just 1% ends up warming the air. By choosing to focus on air temperatures critics are ignoring 99% of the problem.

Are scientists certain that global warming has continued unabated over the last 15 years? Yes. "The best satellite data we have shows that there is still more energy going into the climate system than is going out, because of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere," said Ed Hawkins, at the University of Reading. Another Reading scientist, William Collins, said: "The climate has warmed over the last 10 years, the models are not wrong on the total heat being added."

So where is all the heat going? About 93% goes into the oceans, much of which were largely unmonitored until the 2000s, 3% into land and 3% into melting ice.

Undue focus on the air temperature plateau is cretinous for several more reasons. First, unlike weather, climate is a long term phenomenon and can only truly be assessed over at least 30 years. While the long term warming trend is clear, scientists have long known that air temperatures do not rise smoothly year-on-year in the complex and chaotic climate system and that decade-long ups and downs are part of natural variability.

"The very first climate models built in the 1990s showed this kind of variability, so we have known about this for a long time," said Hawkins. John Shepherd, at the UK National Oceanography Centre, said: "We should prepare for a bumpy ride, as that is what we have had in the past and that is what we will have in the future."

Second, if air temperatures have not risen quickly in the last 15 years, other clear indicators of climate change have worsened more quickly than expected, including the rapid loss of Arctic ice and sea level rise. Critics cannot cherry pick their indicators and remain credible.

Thirdly, many scientists anticipated the so-called "pause": it is not some shock undermining the whole edifice of climate science. A natural and periodic ocean current phenomenon called El Niño peaked in 1998, pumping heat into the air, but has been increasingly in abeyance since. Furthermore, the solar cycle peaked in 2002 and the reached its minimum in 2009, meaning a little less heat beaming down to Earth, and a number of volcanic eruptions have blocked out some sunlight in that time.

So the pause in air temperatures can be well explained and, while work remains to be done determining the exact relative importance of ocean heating, El Niño, solar cycles and volcanoes, we are still only talking about 1% of global warming. Prof David Mackay, the UK's government's chief energy and climate change adviser, is clear: "It is not a terrible mystery."

Another mirage being conjured up is the debate about climate "sensitivity", i.e. how much air temperatures rise for a given rise in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Some scientists have suggested the climate is less sensitive than thought and there is a genuine debate about this. But the differences being discussed are essentially irrelevant. Thomas Stocker, one to the two scientists who oversaw the IPCC report, gave this criticism short shrift: The slightly lower sensitivity being discussed would give humanity only a "few years" longer to tackle climate change, he said: "It is not really a relevant point when it comes to the relevant reductions in CO2 emissions needed to keep temperature rise under 2C."

The estimates of climate sensitivity come out of the complex computers models used to project warming into the future. The IPCC states that the models, built on the basic laws of physics, now accurately represent a great many of the important climate phenomena. "If you are saying the models are flawed, you are saying the laws of physics are flawed," said Tim Palmer, at the University of Oxford.

Be in no doubt, climate change is real and dangerous. In fact, the new IPCC report, written in consensus by the world's climate experts and signed off in unison by the world's governments, may well be too timid. That is because it is a scientific document in which the confidence in climate knowledge and predictions are assessed. It is not a risk assessment.

"If there is a 10% chance of an aircraft crashing, you would not board it, but the IPCC classes that as very unlikely," said Ted Shepherd, at the University of Reading. The IPPC concludes there is a 50-50 chance that global temperatures will exceed 4C this century if carbon emissions are not curbed. Such a rise would have catastrophic consequences. So if you are still feeling confused about all this complex science, it all boils down to this: how lucky do you feel?

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2013

[Flooding via Shutterstock]

What does another Merkel win mean for Europe?

A projection of German Chancellor and leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) Angela Merkel being congratulated by a party member, is beamed onto the side of the Marie-Elisabeth-Lüders-Haus, the German parliamentary library, in Berlin on Sunday…

Copyright © 2025 Raw Story Media, Inc. PO Box 21050, Washington, D.C. 20009 |

Masthead

|

Privacy Policy

|

Manage Preferences

|

Debug Logs

For corrections contact

corrections@rawstory.com

, for support contact

support@rawstory.com

.