The Trinity River washed away their old life during Hurricane Harvey. Repeated flooding and erosion since then never gave it back. The couple got rid of their Ford Mustang Cobra to buy a 1984 Chevrolet truck, until the mud and dirt tore up the truck’s bearings and seals. They traded the truck for a small four-wheel-drive Suzuki Samurai, until the makeshift trails that took over for the roads became too narrow. Then they traded that for a four-wheel ATV, which would often break down, forcing them to walk.

“My next step was gonna be to buy a horse,” Todd said.

Their small rural subdivision in the Trinity River bottom has been slowly abandoned, devastated by flooding and intense rains — the kind of weather that’s becoming more extreme in East Texas due to climate change — prompting a spiral of decline that’s left the area nearly uninhabitable.

Decades ago, there were as many as 100 occupied homes in Sam Houston Lake Estates, a densely-wooded neighborhood about 60 miles northeast of Houston. Today there are fewer than a dozen, according to interviews with locals.

Water hasn’t flowed to the homes in this neighborhood in more than three years — the water company says it can’t get vehicles in to maintain its well — and first responders won’t attempt to navigate the neighborhood’s narrow bridge and eroded dirt roads.

When someone is sick or injured, residents have to drive, or carry, their neighbors out of the woods to reach medical help.

This river bottom flooded often in the past, former residents said, but not like it has in the last decade. Climate change has likely intensified flooding and accelerated erosion, experts said.

“One of the issues is with climate change, we’re going to see more frequent flooding in general,” said Jonathan Phillips, a retired University of Kentucky geography professor who studied the Trinity River. The result for rivers is erosion, he said, which threatens nearby homes.

It used to be easy to live here. Now, it’s not. And that’s pushed people like Todd and Nelson to leave.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/69e85bee7e17944ac79fd278231cbbaf/Managed%20Retreat%204Grid%20COURT.jpg)

Top left: Linda Nelson and Thad Todd stand in front of a “Tiki hut” on their property in Sam Houston Lake Estates in 2014. Top right: A temporary bridge buckles under floodwaters in 2017 following Hurricane Harvey, which isolated part of the community. Bottom left: Thad Todd and Linda Nelson’s house days before Hurricane Harvey hit. Bottom right: Todd and Nelson's dog, Betty, debates whether to take a dip in the rising floodwaters during Hurricane Harvey. “She was always trying to get in to cool off, but we tried to keep her out because of the gators,” Linda Nelson said. Credit: Courtesy of Thad Todd and Linda Nelson

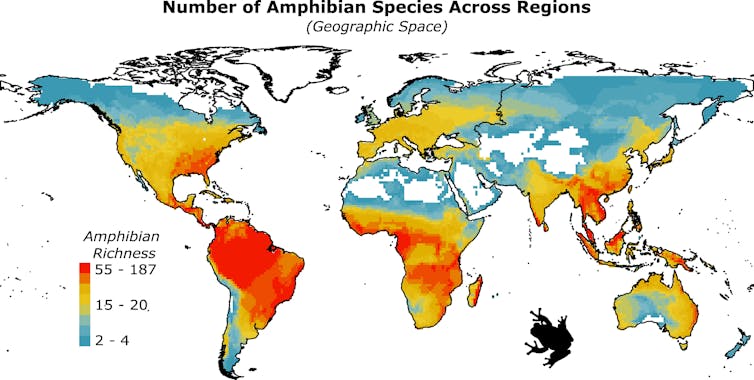

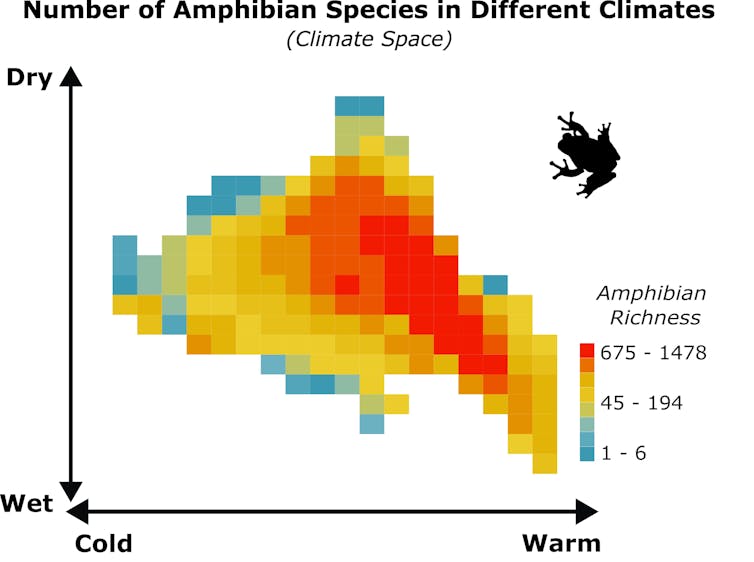

Sam Houston Lake Estates is one example of a global problem as communities reckon with stronger storms, disappearing coastlines, deeper droughts, extreme heat and more devastating fires.

It’s notoriously difficult to track the number of “climate migrants” — people who are forced to abandon their homes due to the effects of climate change — and estimates vary. But an experimental survey by the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that around 3 million adults were displaced by a climate or weather disaster, mostly hurricanes or fires, within the last year.

Between 200,000 and 300,000 Texans are already being displaced by natural disasters each year, the survey indicates.

Floods, whether brought by stronger hurricanes or more intense rain, are expected to be among the most devastating impacts of climate change on Texans, according to the National Climate Assessment. Hurricane Harvey in 2017 was the most significant tropical cyclone rainfall event recorded in U.S. history and caused $125 billion in damage.

Nearly 6 million Texans — about 20% of the state population — now live in an area susceptible to flooding, according to the state’s first detailed analysis of the problem reported this year. Yet only about 753,000 homes, or 14% of Texas homeowners, are covered by flood insurance, according to the Texas Department of Insurance.

In the Trinity River watershed alone, the state’s water agency estimates that more than half a million people live in a 100-year or 500-year floodplain, with at least a 1% or 0.2% risk of flooding each year.

Across the U.S., the federal government has turned to voluntary buyout programs to encourage “managed retreat” from areas that are repeatedly struck by natural disasters. Managed retreat can also include the government forcing residents out by seizing their property through eminent domain. In Harris County, which includes Houston, eminent domain has been used to seize land for flood control projects since at least the 1920s.

Yet state data shows that the money earmarked for buyouts pales in comparison to the number of homes at risk. When Texas received more than $5 billion in federal disaster recovery funds after Hurricane Harvey, the state allocated $189 million for buyouts or land acquisitions in the affected counties — excluding Houston and Harris County, which managed their own $56 million and $194 million buyout programs, respectively.

In the other 37 counties that applied for buyout funds, the state estimated the money would be enough to buy out just over 1,000 homes. That turned out to be optimistic: Later estimates by the counties brought the number down to about 500.

The General Land Office does not track how many total properties were eligible for buyouts, a spokesperson said.

In the end, only 336 homeowners outside the Houston area submitted an application for a buyout; almost all were approved, including fewer than 20 so far in Liberty County, where the average buyout offer has been less than $60,000 — roughly a quarter of what a typical house in the county costs.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/564b7ae70a91dc683a39e4c4cb87b9fc/0627%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2001.jpg)

Kim Click, general manager of the Lake Livingston Water Supply Corp., flips through photos of the flooding around the Trinity River at the water supply office on June 27, 2023. Click said the company decided to cease service in the neighborhood in 2019 after she got one too many calls reporting the road has washed out and that operators could not reach the well or water lines for maintenance. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/2bc03d0ebea2e4307113c3a4550d7289/0627%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2008.jpg)

Phillip Everett, superintendent of the Lake Livingston Water Supply Corp., next to a water tank at the entrance of Sam Houston Lakes Estates. The water supply corporation fills the tank, and residents have to haul water from the tank to their homes since regular water service stopped in 2019. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

“Getting the money they’re getting, it would be hard to find another house somewhere,” said Liberty County Commissioner Greg Arthur.

In Sam Houston Lake Estates, however, the effort is totally stalled: Unable to safely deliver demolition equipment to tear down the flood-damaged homes, which the federal government requires, the county’s grant manager paused buyouts in the neighborhood.

That’s left people like Todd and Nelson with little hope that they’ll ever get the financial help they were promised — and no other option but to abandon their property and start over with nothing.

Six years ago, when Harvey’s rains started to push the Trinity River out of its banks, Todd packed some food, four dogs and a bird named Sidney into a canoe to escape the rising floodwaters. He spent three days trapped on the second floor of a neighbor’s house, grateful that his wife was safe in Oklahoma visiting family. One of their dogs died.

Five feet of water gushed into the one-bedroom house that Todd had spent the better part of a decade building. They lost most of their belongings, including Nelson’s cherished childhood photo albums.

The federal government offered them money to rebuild, but they declined; the house was too damaged to justify the repairs and they were tired of the repeated flooding in the years after Harvey. They wanted to relocate, but didn’t have the money. In other words, they were the perfect candidates for a buyout.

So when a local buyout program opened two years later in 2019, they applied. And then they waited, living in a fifth-wheel trailer next to their rotting home.

“We’ve been through hell and back,” Todd said. “It was crazy. It’s still crazy.”

Nelson had a heart attack in June 2021. She knew an ambulance couldn’t reach her; a neighbor found someone with a four-wheel-drive vehicle to get her out of the woods, then drove her to the hospital. They were just in time.

But it made her and her husband realize they couldn’t wait on the buyout any longer.

A month later, they left everything.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/4bf3f61f2cf67dfe317efb5c4ebbbefc/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2058.jpg)

A small body of water inside Sam Houston Lake Estates, which hugs the Trinity River and has seen repeated, severe floods in recent years that has pushed many residents to leave the community. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

'It was nothing like this'

Advertisements for catfish and signs offering “Cash!” for homes adorn the roads near Sam Houston Lake Estates. As the paved farm-to-market roads fade to dirt, tree branches close in like a tunnel.

Inside the neighborhood, homes are scattered far from one another on plots of cleared forest. Nearby, a community center that in its heyday hosted popular dance nights is now a shell of a metal building with more open air than walls. The locals advise newcomers to stay out of the grass and watch out for snakes, alligators and wild boars.

In August, a late summer drought meant the dirt roads were dry enough for Marvin Stovall, a road foreman for Liberty County Precinct 2, to slowly but skillfully navigate a white pickup around gaping potholes, tree branches and mounds of caked earth to reach the back of the neighborhood and the Trinity River. Most of the homes appeared abandoned, flood-stained, falling apart.

“Back in the day, these houses were really nice,” Stovall said. He grew up in Liberty County and remembers frequenting the dance hall in the 1970s.

“All this right here was really pretty,” he said as he drove past one abandoned home after another. “It was nothing like this at all.”

Sixty years ago, a farmer named Barney Wiggins began to buy this land in the Trinity River bottom. Wiggins, who’d had seven failed crops in six years, according to an obituary for his wife, Bonnie, turned to the real estate business to make a living. He began purchasing and developing land throughout Southeast Texas, advertising cheap rural lots to Houston residents.

Wiggins employed less-than-reputable business practices, such as allowing property owners to swap lots and immediately voiding deeds so he could resell the lots if an owner missed a payment, according to court records. Occasionally, the same lot was accidentally sold to two purchasers.

One 837-acre Wiggins development, with lakes stocked with bass and catfish on the east side of the river, became Sam Houston Lake Estates. A 2-mile road was bulldozed and eventually improved with loads of iron ore, while shorter dirt roads connected the one-acre plots throughout the subdivision. Electricity and water soon arrived, provided by rural utility companies, but sewer lines and garbage collection never did. The property owners association was supposedly responsible for the roads, but one longtime resident called that “a joke,” simply a way for Wiggins to wash his hands of it.

Today, some of the homes are occupied by squatters while others sit abandoned and empty, their insides stripped by thieves. A few are used as weekend homes. In the section closest to the river, just a handful are still owner-occupied.

One of them, a raised one-story wooden house with chipping red paint, is where Kenneth Brister, 77, has lived on the riverbank for a little over a decade. He’s heard talk of buyouts for almost that long and says he doesn’t want one.

“I made it this long with it,” Brister said of his home. “I’ll make it till I die.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/af5227098ab926831414f9a696565979/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2056.jpg)

Marvin Stovall, a road foreman for Liberty County Precinct 2, drives through Sam Houston Lakes Estates. Stovall grew up in the county and used to attend weekend dances in the 1970s at the now-abandoned community center near the neighborhood's entrance. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/183513ce0219a1a86b026d1d9d277867/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2052.jpg)

Sam Houston Lakes Estates resident Kenneth Brister stands in the doorway of his home next to the Trinity River on Aug. 22. Brister, 77, says he's not interested in taking a buyout and plans to stay in his home despite repeated floods. He said he's concerned that a tree branch will soon fall on the power line to his home and wants the electric utility to more frequently maintain the area. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

Residents like Brister have electricity, but the water lines haven’t worked since 2019, when the Lake Livingston Water Supply Corporation got one too many calls reporting that the road had washed out again, meaning their operators couldn’t reach the well for maintenance. The company stopped charging customers for water and started dropping a small, dark-green water tank near the mailboxes. That’s about three miles from where Brister lives.

Last year, the company told the state it wanted to cease that service too, but the Public Utility Commission ordered them to continue.

The county once floated the idea of taking over road maintenance for the subdivision, but an agreement never materialized because the county insisted that the roads meet county codes first. Residents couldn’t get enough money together to fix them.

Brister said he hauls in necessities with his all-terrain vehicle when it's dry enough. Otherwise, he walks. He only brings the ATV to his house when there’s little risk of flooding, and otherwise, he parks it near the mailboxes.

“You got to play with the weather,” Brister said, likening it to gambling.

Because voluntary buyouts usually take years to implement and often fail to relocate the whole community out of harm’s way, buyout programs can leave hollowed-out neighborhoods behind, with fewer services and resources than before the buyout program began, researchers said.

“You want a critical mass to move,” said Chris Hilson, director of the Reading Centre for Climate and Justice, who has researched climate displacement. If people move in “dribs and drabs,” the buyout program wrecks the community web that neighbors built together, businesses stop investing in the area, and government services begin to fall away. And the remaining homes could easily flood again.

One of the biggest challenges is convincing people to leave. The buyout money is often not enough to buy or rent housing elsewhere. And residents tend to misjudge the amount of risk they face from climate disasters because of their emotional attachment to the place, Hilson said.

“It becomes a big part of their identity,” he said.

Buyout programs are supposed to have protections that prevent local governments from removing critical services, said A.R. Siders, an assistant professor at the University of Delaware and member of the university’s Disaster Research Center. But in reality, as fewer people live in an area, it makes less sense to spend tax dollars there. And government officials are hesitant to trample on people’s property rights to force them to leave, she said.

“The idea of individual property rights treats it as though [homes] are isolated, but they’re not,” said Siders, one of the leading researchers on managed retreat. “...Those homes are very dependent on government systems: the roads, the water services, the septic systems, emergency services.”

What many longtime residents of Sam Houston Lake Estates want — reliable roads, help elevating their homes above floodwaters, easy access to clean water — isn’t something a small county with a tight budget can responsibly do, said Arthur, the Liberty County commissioner who represents the subdivision.

“There’s so many things I wish we could do back there, but we can’t,” Arthur said. “I can’t go spending county money on private roads. I wish we could, but we can’t. We got laws to go by.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/89352cd69004efc477d461ec0d843b64/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2063.jpg)

Fred Boyum looks at the remains of a home where one of his neighbors used to live in the Sam Houston Lake Estates neighborhood. Many homes in the area have been abandoned after years of repeated flooding. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

Life in the bottoms

A handful of people opted to leave their flood-damaged homes near the river for rented mobile homes closer to the mailboxes, water tank and still-maintained road.

Tina Cutsinger, 65, traded her old house and property with a neighbor for a reliable truck, then moved into a rented mobile home near the front of the community. She says that she and her neighbors don’t need buyouts. She’s heard it wouldn’t be enough money to buy a new home somewhere else.

If it floods again, she said, “We know we are probably going to get messed up again.”

But, she added, “We can’t afford to live anywhere else. We have no money.”

With little hope of getting help from the government, residents of Sam Houston Lake Estates have tried to help one another navigate their post-Harvey reality.

For years, Edward Gibson, 68, who lives in a house at the front of the neighborhood, used a tractor to fill the holes in the roads, trying to make the back of the neighborhood drivable. But it seemed like each time he fixed it, the river washed it out again.

“It just wasn’t gonna happen,” he said.

Another resident, Fred Boyum, 53, said that after Harvey, he began hauling groceries to his friends who couldn’t make the trek in and out of the neighborhood. He stuffed an old Army backpack with water, food, and medical supplies and hiked the two miles or so to their houses. They usually paid him with a six-pack of beer, he said.

He constantly worried about neighbors with medical problems.

“When my good friends have to leave, I’m happy, because it’s for their own good,” Boyum said. “It’s a bitter but happy kind of thing.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/e053e57d657d77d291c1fa0b4c6d22a2/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2059.jpg)

Fred Boyum stands outside of his home, a hunting property that he converted to his full time residence, at the entrance of Sam Houston Lake Estates. "When my good friends have to leave, I'm happy, because it's for their own good," he said. "It's a bitter but happy kind of thing." Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8b097a38f3786629b5400e1388ed52f7/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2037.jpg)

Edward Gibson checks on his various pets outside of his home at the entrance of Sam Houston Lakes Estates on June 28. Gibson said he tried filling in the holes in the neighborhood's roads with his tractor but it was a losing battle and he gave up. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

Medical emergencies are chief among the county’s concerns for the area, Arthur said.

Liberty County bought two military-grade trucks at a government auction a few years ago that can navigate the terrain and pick up residents during an emergency, he said. But that’s not a long-term solution — he wants to buy out as many residents along the river bottom as possible.

“I’m hoping that people can get out of those situations,” he said. “It’s a health and safety issue not being able to get in and out.”

Linda Nelson knows that better than anyone. On a June morning in 2021, she woke up feeling sick. Todd offered to stay home with her, but she told him no, go on to work.

He was 50 miles away when she had a heart attack.

If it weren’t for the neighbors who got her to the hospital, she said, “I wouldn’t have made it.” She was in the hospital for four days. And after that, things changed.

“We were worried, if I have another one, am I gonna get out of here?” she said.

“That just broke the camel’s back,” Todd said. A few days after Nelson came home from the hospital, he called her from work: “Do you wanna get out of here?”

They started packing for Oklahoma.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/56d2324c4dcbb733c876212e1731a126/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2069.jpg)

Robert Lawrence and his wife Jinelle outside their home in Cleveland, less than 10 minutes from the home they had to abandon in Sam Houston Lake Estates after Hurricane Harvey flooded it. "What I loved the most was that we could ride our horses anywhere we wanted," Jinelle Lawrence said of living in the neighborhood. After Harvey, they had to give away their horses. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

Bought out

Even those who got the buyout money say it’s a long and difficult process.

Robert and Jinelle “Linda” Lawrence, for example, still miss the life they created in Sam Houston Lake Estates, where they spent their free time rescuing the many stray dogs and cats wandering through the rural area.

They waited as long as they could to evacuate during Harvey — they couldn’t bear to leave their animals, including two horses. For four days afterward, they waded in chest-high water to drop off cat and dog food.

Volunteers had rescued the horses, but one had “river rot” on his hooves. He would recover, the veterinarian said, but it forced the Lawrences to confront their reality: A floodplain was just too dangerous for the horses — and for them. They were broke and living in their son’s house. They gave up their animals, with a plea: “Just find them a home away from the [river] bottom.”

Since then, they’ve made do, buying necessities from flea markets to furnish their trailer home in Cleveland, less than a 10-minute drive from their old house, where they now live on a portion of what was their son’s property. They used most of their buyout money to pay for the land and bought the trailer on installments.

“I didn’t think I’d ever live back in a trailer home,” Jinelle Lawrence, 70, said.

It would help if they had the other $15,000 they were initially promised by the county, a bonus for remaining in Liberty County. But because they bought the trailer and the land separately, their grant manager told them they don’t qualify.

Liberty County received $6.7 million from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to fund its housing buyout program. Harvey flooded more than 5,000 homes in the county in 2017, and 70% of the money was earmarked for low-to-moderate income households. Only about 50 offers have been made, almost all to residents living close to the river, according to data provided by GrantWorks, the company managing the program, and 17 buyouts have been completed.

The deadline to apply is at the end of October, but the company hasn’t received any new applications in months, said Tyler Smith, the grant program manager. The buyout offers are technically capped at $331,770 for a single-family home, but usually the county offers far less than that: The buyouts have ranged from about $20,000 to $180,000, Smith said.

The average offer is $58,000. The median home price in Liberty County is $224,000.

The Lawrences were paid only $19,700, including a roughly $5,000 moving stipend, for the lake house where they lived from 1997 to 2017, documents show, even though the home was valued at $39,700 in an appraisal. After back taxes and a Harvey-related insurance claim were subtracted, the offer was slashed in half.

“I feel like we got messed over,” said Robert Lawrence, 71, who is retired, but “it’s the government and there ain’t nothing we can do about it.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/d0d54c4ec8904f57690c7cb1e6366a44/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2067.jpg)

“I didn’t think I’d ever live back in a trailer home,” Jinelle “Linda” Lawrence said. Their new mobile home in Cleveland sits on land that they bought from their son, using part of the money from their buyout. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/5908757e4332abf4937e5c805a7cfebe/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2070.jpg)

Ducks form a line outside of the Lawrences' home. The couple loves animals and while they lived in Sam Houston Lake Estates, spent much of their free time rescuing the many stray dogs and cats wandering through the rural area. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

Smith said homeowners are offered pre-storm value for their property. If the offer is accepted, the government is supposed to demolish the structure and attach a deed restriction to ensure the property will forever be open space. Ideally, it returns to nature.

It’s been more than six months since the Lawrences got a check, but their old house still hasn’t been torn down.

“They told us they would be flattening it down, and that’s the main reason I wanted to go ahead with the buyout, because I wanted it flattened,” Jinelle Lawrence said. “I don’t want someone trying to live in it and get hurt.”

Smith said they can’t figure out how to get the necessary equipment to some of the homes in Sam Houston Lakes to demolish them. If they can’t tear down the homes, the county is violating the terms of the federal money. There are six homes in the neighborhood, he said, that qualified for a buyout but are too isolated to demolish.

One of those homes is Todd and Nelson’s. Unlike the Lawrences, they never got the money they were told they’d get for the buyout, which stalled once the grant managers realized the dilemma. That means that Todd and Nelson must keep paying property taxes — which are rising every year in Liberty County — for a home they were forced to abandon.

“We should’ve been paid a long time ago,” Nelson said. She said their property taxes shot up to $3,000 this year, from about $600 in prior years. “They’re not doing what they said they were gonna do.”

Smith said GrantWorks is planning to hire contractors to construct a temporary road that will allow them to tear down the homes; the proposal is currently going through an environmental evaluation. It’s unclear when the demolitions might actually occur, but Smith said he hopes they’ll be able to finish sometime this year.

Smith has worked in disaster recovery housing for more than a decade and said he’s never encountered a situation like this.

“The people who own Harvey-damaged homes that are so severely impacted that there’s not even a road to their house anymore should be your ideal candidate for a buyout,” Smith said. “It’s a big problem.”

“No one should live there,” Smith added. “There should be no house there.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8ce4b8a4e0f6fa63ab05aac696d8423f/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2021.jpg)

Ray Tarver takes a break while mowing the lawn around his home in New River Lake Estates on June 28. Tarver and his wife Shirley are seeking a buyout for their property but are in limbo due to a property dispute with Shirley’s late sister’s husband, who is in prison. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

Up the river

About five miles up the river from Sam Houston Lake Estates, Ray and Shirley Tarver, both in their 60s, feel like they’re being held captive in their own home. Ray packed a trailer full of stuff months ago, but their buyout is tied up in a legal dispute with Shirley’s late sister’s husband, who is in prison and hasn’t agreed to sell the property.

“If that guy signed that paper, we’d probably be next week selling out,” Ray Tarver said. “[We’re] sitting around waiting on a buyout, waiting on a signature.”

The Tarvers live in a neighborhood called New River Lake Estates. The roads are easily drivable and the water lines work. But the road to New River Lake Estates hugs the Trinity, and the river is taking more land every year. When it floods, there’s only one way out: by boat.

Liberty County offered them $170,000 for the ranch-style home and land that Shirley’s grandmother bought in the late 1960s. Her grandmother passed it down to her kids, and eventually Shirley bought the property from her father. She’s lived there for 30 years.

“You have to look at it this way: What happens if it floods, and they make everybody move, and don’t even give you that?” Shirley Tarver said.

The Tarvers consulted with attorneys, sent letters, and had more phone calls with their buyout program manager than they can count. They still plan to move to Hancock County, Mississippi, where Ray’s family lives, if they ever get the money, but they’re starting to lose faith.

“I’m almost to the point where I’m ready to say, ‘Never mind, I’m just gonna stay here,’” Shirley Tarver said.

While the Tarvers look for a way out, down the street in the same neighborhood, new residents have moved in since Hurricane Harvey. Hector Torres Vasquez, 48, said he bought his property in New River Lake Estates in 2019 to relocate his auto shop from Houston to a quieter area. He said he wasn’t aware of the buyout program.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/7c76226a07eb43cd26c5548619186d68/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2027.jpg)

Hector Torres Vasquez works on his property in New River Lake Estates on June 28. Vasquez, who bought the place in 2019, said he hadn’t heard about the buyout program for homeowners who want to leave the flood-prone area. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/fb4e84846737e7c77cfa5a5578def122/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2026.jpg)

A chicken cares for its chicks on Vasquez's property. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

Katharine Mach, a professor at the University of Miami who has studied managed retreat, said these sorts of problems — people moving in at the same time as the government is trying (and often, failing) to move people out — are common when the “carrots” offered to relocate aren’t enough.

Because it’s expensive and politically unpopular, it’s rare for the government to turn to eminent domain to condemn private property and relocate people out of areas affected by climate disasters, experts said.

Researchers are exploring new strategies to convince people to leave disaster-prone areas and avoid the red tape that homeowners in the Trinity River bottom are experiencing. Siders, of the University of Delaware, said that governments could present residents with an offer that’s not tied to the value of their property, but the price for comparable housing nearby.

Though more local governments, researchers, and nonprofits are thinking about new ways to “manage retreat” due to climate change, researchers say it remains extraordinarily difficult to do well.

“When funding is tied to post-disaster funds, as it has been for basically all [federally funded] buyouts, there’s this massive cognitive disconnect between the time when the flood happens, and then the five or 14 years later, when the buyout eventually occurs,” Mach said.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/b504d64de373474feb665098d7bd4fb8/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2051.jpg)

Gulf fritillary butterflies visit a Brazilian vervain near the Trinity River inside Sam Houston Lake Estates. Residents take pride in the beauty of the area, and Texas Parks and Wildlife intends to create a new state park, called Davis Hill, nearby. Credit: Annie Mulligan for The Texas Tribune

'I’ll make a home'

Just south of Warner, Oklahoma, Linda Nelson’s aunt lives in a quaint ranch-style home on a large plot of land where she’s let Nelson and Todd park a travel trailer.

They’re 10 miles from the nearest major river and the dirt road to their place is free of potholes. This land in the Cherokee Nation is where Nelson grew up, and where she and Todd met 40-something years ago, when Linda was only 14 and Thad was 21, working at an iron and metal recycling facility.

“I didn’t even like him then,” Nelson said, for the record.

They didn’t fall in love until decades later, after Nelson had married and divorced, and Todd was living in Texas for work. One day, he said he wondered about his old friends in Oklahoma — and about a girl he’d known there.

He drove to Oklahoma and showed up at her mother’s house, where a woman with dyed red hair ran to him, wrapped her hands around his neck and started crying. All he could say was, “Who is this?” He hadn’t seen her in 16 years.

“We started seeing each other after that,” said Nelson, a natural brunette. “One thing led to another.”

In 2000, she followed Todd to Texas. In 2008, they bought the property near the Trinity River, with the small lake house that Todd fixed up himself.

Two decades later, they returned to Muskogee County, shaken by Nelson’s heart attack and hauling just a small trailer of belongings.

A family member had asked if they could use a bare-bones, 30-foot travel trailer until they got on their feet — or until the $51,000 from Texas came that would buy a nicer one.

“I said, ‘I’ll make a home out of it,’” Todd said, “and I’m working on it now.”

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/69e85bee7e17944ac79fd278231cbbaf/Managed%20Retreat%204Grid%20COURT.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/564b7ae70a91dc683a39e4c4cb87b9fc/0627%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2001.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/2bc03d0ebea2e4307113c3a4550d7289/0627%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2008.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/4bf3f61f2cf67dfe317efb5c4ebbbefc/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2058.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/af5227098ab926831414f9a696565979/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2056.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/183513ce0219a1a86b026d1d9d277867/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2052.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/89352cd69004efc477d461ec0d843b64/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2063.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/e053e57d657d77d291c1fa0b4c6d22a2/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2059.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8b097a38f3786629b5400e1388ed52f7/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2037.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/56d2324c4dcbb733c876212e1731a126/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2069.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/d0d54c4ec8904f57690c7cb1e6366a44/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2067.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/5908757e4332abf4937e5c805a7cfebe/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%20TT%2070.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8ce4b8a4e0f6fa63ab05aac696d8423f/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2021.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/7c76226a07eb43cd26c5548619186d68/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2027.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/fb4e84846737e7c77cfa5a5578def122/0628%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2026.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/b504d64de373474feb665098d7bd4fb8/0822%20Liberty%20Co%20Buyouts%20AM%2051.jpg)