Opinion

The real story with Obamacare IT woes is out-of-control private contractors

Whatever the ultimate benefits of Obamacare, it's clear that the rollout of its $400m registration system and website has been a disaster. Healthcare.gov was unusable for millions who visited the site on launch day earlier this month, and the glitches reportedly continue. What went wrong?

Of course, the Obama administration is to blame for the botched rollout, but there are other culprits getting less attention – namely, global tech conglomerate CGI, which was responsible for the bulk of the execution, and in general the ability of big corporations to get massive taxpayer-funded contracts without enough accountability.

Government outsourcing to private contractors has exploded in the past few decades. Taxpayers funnel hundreds of billions of dollars a year into the chosen companies' pockets, about $80bn of which goes to tech companies. We've reached a stage of knee-jerk outsourcing of everything from intelligence and military work to burger flipping in federal building cafeterias, and it's damaging in multiple levels.

For one thing, farming work out often rips off taxpayers. While the stereotype is that government workers are incompetent, time-wasters drooling over their Texas Instruments keyboards as they amass outsized pensions, studies show that keeping government services in house saves money. In fact, contractor billing rates average an astonishing 83% more than what it would cost to do the work in-house. Hiring workers directly also keeps jobs here in the US, while contractors, especially in the IT space, can ship taxpayer-funded work overseas.

Fortunately, then, there are alternatives to outsourcing public functions to big corporations padding their profits at taxpayers' collective expense, and it is time we used them.

To this end the Healthcare.gov experience should serve as a wake-up call to President Obama, who, after all, said early in his first term he wanted to rein in the contractor-industrial complex, and to the state governments doling out multi-million dollar contracts. The revelation here is that an overdependence on outsourcing isn't just risky in terms of national security, extortionate at wartime, or harmful because it expands the ranks of low-wage workers; it's also messing with our ability to carry out basic government functions at a reasonable cost.

Like many contractors, CGI got an open-ended deal from the government, and costs have ballooned even as performance has been abysmal. The company – the largest tech company in Canada with subsidiaries around the world – was initially awarded a $93.7m contract, but now the potential total value for CGI's work has reportedly tripled, reaching nearly $292m.

Sadly, Healthcare.gov is but one high-profile example of the sweet deals corporations get to do government work—even as they fail to deliver. For other recent examples, one need only look at the botched, taxpayer-funded overhauls of the Massachusetts, Florida and California unemployment systems, courtesy of Deloitte.

In Massachusetts alone, professional services giant Deloitte got $46m to roll out a new electronic system for unemployment claims. The company, whose private-sector whippersnappers were expected to lap the crusty bureaucrats the state employs directly, delivered the project two years late and $6m over budget. On top of that, the system has forced jobless residents to wait weeks to months to collect benefits. One unemployed man who filed a claim for benefits instead received an erroneous bill charging him $45,339. A slap in the face of absurd proportions.

Similarly, the rollouts in Florida and California, which each cost about $63m, can only be described as train wrecks: late, over budget and riddled with glitches that delayed payments to the jobless.

It doesn't have to be this way. We can save money, create good jobs, and get more for each taxpayer dollar by simply by in-sourcing government work. Doing so would mean actually having faith that the government can employ top talent instead of making unfounded assumptions that anyone receiving a government check is a waste of space who can't possibly innovate. Think about it: Why couldn't we, the taxpayers, have just directly hired the finest minds in tech to build Healthcare.gov?

Unfortunately, while Obama promised to focus on insourcing at the start of his presidency, federal workers have instead received multiple kicks in the teeth. There are now 20%, or 676,000, fewer federal workers since the size of that workforce peaked in mid-2010. Recall, too, that Obama froze federal worker pay for two years following the 2010 congressional elections. Now the sequester – a fancy word for the government cuts that started this year – is causing further damage, and could cost 100,000 more federal jobs within a year. Deep cuts to state and local governments continue at the same time.

If we're not going to insource work – presumably because anti-government types successfully peddle the useless bureaucrat stereotype – we should at least have a better process for picking contractors that benefit from taxpayer largesse to carry out public projects. It may be hard to believe in light of the Healthcare.gov experience, but there are examples of successful government outsourcing arrangements in IT. One key to their success, a Government Accountability Office study pointed out, is consistent communication with, and monitoring of, contractors. Penalties for cost overruns, failing to deliver by agreed-upon deadlines and other forms of mismanagement would help, too.

Of course, we also need a more competitive bidding process, and a more thorough examination of the track record of any company up for a giant government contract.

Putting all of these systems in place takes time and money, which is one reason why direct government hiring is preferable. But regardless of whether we start insourcing or improving oversight or both, one thing is clear: we need to stop blindly throwing taxpayer money at corporations while not holding them accountable.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2013

Saving the planet from short-term thinking will take 'man on the moon' commitment

"We choose to go to the moon." So said John F Kennedy in September 1962 as he pledged a manned lunar landing by the end of the decade.

The US president knew that his country's space programme would be expensive. He knew it would have its critics. But he took the long-term view. Warming to his theme in Houston that day, JFK went on: "We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too."

That was the world's richest country at the apogee of its power in an age where both Democrats and Republicans were prepared to invest in the future. Kennedy's predecessor Dwight Eisenhower took a plan for a system of interstate highways and made sure it happened.

Contrast that with today's America, which looks less like the leader of the free world than a banana republic with a reserve currency. Planning for the long term now involves last ditch deals on Capitol Hill to ensure that the federal government can remain open until January and debts can be paid at least until February.

The US is not the only country with advanced short-termism; it merely provides the most egregious example of the disease. This is a world of fast food and short attention spans; of politicians so dominated by a 24/7 news agenda that they have lost the habit of planning for the long term. Britain provides another example of the trend. Governments of both left and right have for years put energy policy in the "too hard to think about box". They have not been able to make up their minds whether to commit to renewables (which is what Germany has done) or to nuclear (which is what the French have done). As a result, the nation of Rutherford is now prepared to have a totalitarian country take a majority stake in a new generation of nuclear power stations.

Politics, technology and human nature all militate in favour of kicking the can down the road. The most severe financial and economic crisis in more than half a century has further discouraged policymakers from raising their eyes from the present to the distant horizon.

Clearly, though, the world faces long-term challenges that will only become more acute through prevarication. These include coping with a bigger and ageing global population; ensuring growth is sustainable and equitable; providing the resources to pay for modern transport and energy infrastructure; and reshaping international institutions so that they represent the world as it is in the early 21st century rather than as it was in 1945.

Pascal Lamy had a stab at tackling some of these difficult issues last week when he presented the findings of the Oxford Martin Commission for Future Generations, which the former World Trade Organisation chief has been chairing for the past year.

The commission's report, Now for the Long Term, looks at some of so-called megatrends that will shape the world in the decades to come, and lists the challenges under five headings: society; resources; health; geopolitics and governance.

Change will be difficult, the study suggests, because problems are complex, institutions are inadequate, faith in politicians is low, and short-termism is well-entrenched. It cites examples of collective success – such as the Montreal convention to prevent ozone depletion, the establishment of the Millennium Development Goals, and the G20 action to prevent the great recession of 2008-09 turning into a full-blown global slump. It also cites examples of collective failure, such as depletion of fish stocks and the deadlocked Copenhagen climate change summit of 2009.

The report comes up with a range of long-term ideas worthy of serious consideration. It urges a coalition between the G20, 30 companies and 40 cities to spearhead the fight against climate change; it would like "sunset clauses" for all publicly funded international institutions to ensure they are fit for purpose; the removal of perverse subsidies on hydrocarbons and agriculture, with the money redirected to the poor; the introduction of CyberEx, an early warning platform aimed at preventing cyber-attacks; a Worldstat statistical agency to collect and ensure the quality of data; and investment in the younger generation through conditional cash transfers and job guarantees.

Lamy expressed concern that the ability to address challenges is being undermined by the absence of a "collective vision for society". The purpose of the report, he said, was to build "a chain from knowledge to awareness to mobilising political energy to action".

Full marks for trying, but this is easier said than done. Take trade, where Lamy has spent the past decade, first as Europe's trade commissioner then as head of the WTO, trying to piece together a new multilateral deal. This is an area in which all 150-plus WTO members agree in principle about the need for greater liberalisation but in which it has proved impossible to reach agreement in talks that started in 2001.

Nor will a shake-up of the international institutions be plain sailing. It is a given that developing countries, especially the bigger ones such as China, India and Brazil, should have a bigger say in the way the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are run. Yet it has proved hard to persuade countries in the developed world to cede some of their voting rights and the deal is still being held up owing to foot-dragging by the US. These, remember, are the low hanging fruit.

Another conclave of the global great and good is looking at what should be done in one of the much tricker areas, climate change. The premise of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate is that nothing will be done unless finance ministers are convinced of the need for action, especially given the damage caused by a deep recession and sluggish recovery. Instead of preaching to the choir, the plan is to show how to achieve key economic objectives – growth, investment, secure public finances, fairer distribution of income – while protecting the planet. The pitch to finance ministers will be that tackling climate change will require plenty of upfront investment that will boost growth rather than harm it.

Will this approach work? Well, maybe. But it will require business to see the long-term benefits of greening the economy as well as the short-term costs, because that would lead to the burst of technological innovation needed to accelerate progress. And it will require the same sort of commitment it took to win a world war or put a man on the moon.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2013

How young heroines helped redefine girlhood as a state of strength

Malala is one of a number of girls being idolized by adults – following a change parallel to the women's movement of the 1960s and 1970s

When Malala Yousafzai, the 16-year-old schoolgirl and youngest Nobel nominee, appeared on the Daily Show earlier this month, host Jon Stewart seemed, for the first time, disarmed. Later, he'd be left speechless by her eloquence but his first, stuttering words to her were: "It's honestly humbling to meet you. You are 16..."

Those two statements sum up an internationally felt, two-part awe: first, how is she so brave and formidable and, second, how is she so young?

Malala has been a campaigner for girls' rights to education since she was 11, when she began blogging for the BBC about life in Pakistan under Taliban rule, but she became an international symbol of peaceful resistance and valour after an attempt on her life last year.

She has said that up until then, despite being told that she was a target, she couldn't believe that anyone would try to shoot a teenage girl. Instead: "I was worried about my father [also an activist] – we thought that the Taliban are not that much cruel that they would kill a child."

Her courage and her achievements are enormous regardless of her youth: she has defied arguably the world's most tyrannical and brutal regime and she not only survived an assassination attempt at 15, but was emboldened by it. In a speech delivered at the United Nations soon afterwards, she said: "The terrorists thought that they would change our aims and stop our ambitions but nothing changed in my life except this: weakness, fear and hopelessness died. Strength, power and courage was born."

All this is more than enough to justify the worldwide adulation she has elicited. But what makes her compelling even beyond this, and why she will endure, is the fact of her girlness. Like her, we all find the idea of someone shooting a child in the head unconscionable. But when that child is a girl, it seems more shocking: we are told that girls are vulnerable, more vulnerable than boys. More insidiously, we are told that girls are trivial, dismissible and inherently risible. The word "girl" remains something like an insult – to throw like a girl, to act like a girl, to cry like a girl.

US secretary of state Hillary Clinton seemed to acknowledge this girl-scorn and to celebrate its subversion when she joined the ranks of world leaders praising Malala. Speaking in April, she said: "The Taliban recognised this young girl, 14 at the time, as a serious threat. And you know what? They were right. She was a threat. "

Malala, then, is not just an emblem for peace: she's heralding a shift in the way we valorise and lionise girlhood.

Lorde, aka 16-year-old New Zealander Ella Yelich O'Connor, has not survived gunshot wounds to the head or been nominated for the Nobel peace prize, but she is, like Malala, now a near-global teenage heroine. (One who's just released a debut album aptly, if impudently, named Pure Heroine.) There isn't anything novel or remarkable about a teenager topping the charts – youth has always been pop's favourite commodity – but there is everything novel and remarkable about a school age pop star who speaks eloquently about feminism, cites writers such as Wells Tower and Tobias Wolff as influences, and references the relationship between Raymond Carver and Gordon Lish. Lorde's poise and precocity are at play in Royals, which has been the number one song in the US for the past three weeks. This has to be the first time that a critique of wealth – sly and knowing and lyrical and written by a schoolgirl – has found itself a number one hit.

Lorde has a fan, and vice versa, in 17-year-old Tavi Gevinson, who began her career at 11 with Style Rookie, a fashion blog so astute that national news outlets suggested it was written by an insider.

In the years since then Gevinson has deftly navigated her way from fashion world curio – a granny-spectacled cutie whom famous people loved having their picture taken with – to a global media powerhouse, a 17-year-old public figure idolised by as many adults as teens. Rookie, founded in 2011, announces itself as a site for teenage girls, but with some of the most enlightened interviews and columns around, it has found as passionate an audience among grown women. I'm nearly 30, but, like every woman I know, I read her website every day.

As the online magazine Slate put it recently: "People seem to recognise that Tavi Gevinson is doing great things for girls. The truth is actually much more impressive: She is doing great things. Adults need not turn to Rookie out of nostalgia or to experience catharsis. Read it because it is singular."

Among several grown women employed by Gevinson (her staff reportedly refer to her as "tiny boss")is 42-year-old Anaheed Alani, who has said: "I said I wouldn't work for anyone who isn't smarter than me, and it's still the case."

Of the many astute things to come out of Gevinson's mouth, this might be the most important: "Feminism to me means fighting. It's a very nuanced, complex thing, but at the very core of it I'm a feminist because I don't think being a girl limits me in any way."

Figures such as Tavi, Malala and Lorde – girls publicly admired for their convictions and the boldness of their actions – might help us all reclaim "girlhood" as a state of strength. Through them, we might start to think of the term "teen idol" differently. We might, in fact, upend it entirely. Because rather than pubescent celebrities adored by tweens (and monetised by the music and movie industries) for their non-threatening attractiveness, these are teenagers idolised by adults for their intelligence and courage.

Pop culture loves the kick-ass version of girlhood. It's a lineage that began in the girl-power 1990s with Buffy the Vampire Slayer and runs on to Xena: Warrior Princess and Katniss of The Hunger Games. But, to put it bluntly, these girl characters are presented as heroes simply through the violence they enact. They look cool doing it (Jennifer Lawrence smouldering down the sightline of a bow and arrow in The Hunger Games, an avenging Hailee Steinfeld toting a pistol in True Grit, or Chloe Moretz karate-kicking as a superhero in the Kick Ass movies) but, to borrow Malala's words: "If you hit a Talib with a shoe, then there would be no difference between you and the Talib. You must not treat others with cruelty and that much harshly; you must fight others through peace and through dialogue and education."

To put it another way, the heroism of peaceful activism is greater than the slings and arrows of outrageous badassery.

Consider Tuesday Cain, a 14-year-old who protested against the abortion laws in Texas with a sign that read, "Jesus isn't a dick so keep him out of my vagina" and was called a "whore" online. But, writing on women's website xojane.com, she said that the experience hasn't made her any less passionate "about fighting for a woman's right to choose and the separation of church and state".

Ilana Nash is an associate professor at Western Michigan University in the gender and women's studies department and the author of American Sweethearts: Teenage Girls in Twentieth-Century Popular Culture. I ask her why it is that the culture is yielding these real life girl-heroes now.

"Teenage girlhood has followed a parallel motion to the women's movement of the 1960s and 1970s," she says. "Just as it was a result of second-wave feminism for women to become political icons, so is it now possible for teenage girls to be admired and publicised as political agents. In other words, girlhood is starting, in a small way, to follow the same trajectory that adult womanhood has in the last generation."

She also identifies as a factor "the student-centred classroom" educational movement of the 1990s, whereby America's public schools put the student and his or her needs first.

"Our shift towards making young people a 'centre' of discussion," she says, "is that we are now more inclined to take seriously the actions of young people. When a young person of either sex does something politically amazing or socially powerful, we are more prone to give it headline space. Especially young females."

The artist Lorde beat to the number one spot is Miley Cyrus, but it would be reductive to take this as some kind of symbolic triumph of thoughtfulness over sexiness (as though the two are mutually exclusive). More noise, after all, has been made over Cyrus's body than Lorde's words. "It is still a world where sexiness and cuteness dominate our images of girls," Nash agrees. "The difference now is that it's no longer the only story being told. There is a widening of the discourse – discussing teen girls as political agents is now part of what is possible."

In a recent interview with Kamila Shamsie, Malala reflected on the Talib who shot her: "He was quite young, in his 20s ... he was quite young, we may call him a boy."

We might – and allowing him his youth is an act of almost superhuman magnanimity on her part. When she calls him a boy, she's virtually pardoning him. In contrast, when we now call her a girl we're simply paying her a compliment.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2013

For Republicans, federal workers are nothing but ideological pawns and punching bags

In a just universe, America's civil servants would be back at work and Congress would be on indefinite furlough.

Federal workers don't create budget crises, yet whenever we have one, they're the ones getting screwed. This time is no different. They can take some comfort in the rock-bottom approval ratings for Congress – currently hovering somewhere between hemorrhoids and Charles Manson – and specifically for the House Tea Party caucus that precipitated the shutdown. But this is an old story: we all hate Congress, but love our own representatives. Members of Congress don't answer to national polls, they answer to their constituents. And thanks to redistricting, a large chunk of the House Republicans are insulated in ultra-conservative districts that have been gerrymandered to a point beyond all recognition to the rest of the country (while the remainder live in fear of getting challenge in the primaries if they don't go along with the former's reckless endeavors).

This is why Representative Ted Yoho, described by the New York Times as "a freshman Florida Republican who had no experience in elective office before this year [who] said the largest economy on earth should learn from his large-animal veterinary practice", suggested "if they're not working, they shouldn't get paid", regarding those federal workers he helped put out of work. Yoho wasn't just spouting off; he was at a town hall meeting responding to a caller from his home district who complained about the federal workers "at home watching Netflix or whatever", as if being furloughed had been their choice.

In the end, even Congressman Yoho went along with the rest of the House, which unanimously voted to provide back pay to furloughed workers whenever the shutdown ends. But the promise of a check at some uncertain, future date doesn't cover rent, groceries or electricity bills now for the 800,000 workers affected, many of whom live paycheck to paycheck. Federal workers have reported taking out loans, selling possessions on eBay, and getting second jobs (the Department of Energy helpfully posted guidelines for moonlighting: bartending is OK, lobbying for energy companies is not). In a member survey by the National Treasury Employees Union, 84% reported cutting back (pdf) on necessities, and nearly half have delayed medical treatment to save money.

Elizabeth Lytle, a furloughed administrative program assistant with the Environmental Protection Agency in Illinois and retired navy reservist, says:

The shutdown has put tremendous financial stress on my family. There's no money coming in. In September my husband was laid off, and I was furloughed the first of October. And if the VA doesn't get any money, I won't get my disability check at the end of the month.

As for back pay, "I'll believe it when I see it." Lytle notes that as a result of the EPA shutdown, cleanup at a nearby superfund site in Waukegan (the former location of a large outboard-boat-motor manufacturing plant and a former railroad tie, coal gasification, and coke plant facility) has stopped.

Yet it's not just a matter of a handful of stubborn legislators. Politicians like Yoho reflect a nasty political current within a part of the American electorate: that civil servants like Lytle are not real workers, that they don't matter, that their livelihoods are expendable for the sake of some broader ideological agenda.

It's reflected by conservative radio host Laura Ingraham gloating "Starve the beast!" in response to furloughs at the IRS, by Tea Party protesters heckling White House police with calls of "brownshirts" and "Stasi".

Starve the beast! "@politico: Furloughs to shut down IRS for a day: https://t.co/eKANDoRnpN"

— Laura Ingraham (@IngrahamAngle) May 15, 2013

It could be seen during the last round of furloughs resulting from sequestration (for which workers did not receive back pay), when Fox News' Neil Cavuto wondered out loud if this isn't a good thing:

Maybe we have too many federal workers in the first place period, if there's any place to cut it's got to be there.

Civil servants make a handy punching bag. They're to blame for deficits, although total expenditures on federal employees (both civilian and military) make up about 13% of the federal budget far less than Social Security or Medicare, and, according to Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, firing every single federal worker in the country would only shrink the deficit by a third. It's an easy sell to balance budgets on the backs of civil servants: the last budget crisis resulted in federal workers being denied cost-of-living raises for the third straight year, along with agency budget cuts and layoffs. In their competing budget proposals, both President Obama and Paul Ryan agreed to cutting federal employee retirement benefits; the only question is by how much.

Anti-government hysteria has fueled everything from congressional kamikaze attacks on Obamacare to actual kamikaze attacks on federal buildings, and those who get hurt are inevitably people doing their jobs.

Bureaucracies are easy to despise when they make us wait at the Department if Motor Vehicles and take for granted when they fix the roads, but no society of laws can function without one. Now that veterans' and Social Security claims are going unprocessed, food is not being inspected, parks are closed, and Head Start programs are not staffed, maybe the anti-government caucus will change its tune. But don't count on a salmonella outbreak or two changing much. Things might be different if voters elected more federal workers to Congress.

The few existing 'reasonable Republicans' could oust House Speaker John Boehner

House Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio addresses reporters at the Capitol, Oct. 10. House Republicans are still weighing a short-term debt-limit increase. Op-ed contributor Jeremy D. Mayer writes: This deal 'won’t eliminate the debate over spending…

Ignore the spin: This debt ceiling crisis is not just politics as usual

Never before has a minority party linked controversial legislative demands with a threat to shut down the government or imperil the global economy. But House Republicans would have you believe otherwise. In an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal this morning…

The only thing crazier than the shutdown is Fox News' coverage of it

Government shutdown theater has given us some surreal moments. Heard of the "trillion-dollar coin"? Obama actually mentioned it on Monday. It's a half-serious solution that some wonks have floated to solve the debt ceiling crisis, if "floated" is the right word for a coin that figures into most people's imagination as a giant, sweepstakes-style money cartoon.

Then there's Senator Ted Cruz reading children's books on the US Senate floor, a move that will undoubtedly give future historians and/or alien visitors curious ideas about the possible role of star-bellied sneetches (Cruz is a fan of Dr Seuss books) in our legislative process. Constant references to hostage-taking and suicide bombers will provide those same analysts with an exaggerated (though not by much) picture of gun violence in the early 21st century.

But you haven't witnessed the truly crazy until you turn on Fox News or browse the right-wing websites.

Here's a piece of absurdism you can appreciate right now: the image of a janus-faced conservative media talking head, with one mouth defiantly denouncing the impact of the government shutdown, and the other wailing at the costs of keeping government going. Sean Hannity, no great advocate of consistency anyway, has sputtered these two thoughts within minutes of each other. "The government is not totally shut down! Seventeen percent is it!" he told listeners Monday, before confiding that he believes the GOP will prevail, since "the public will side with the group that's willing to talk".

Laura Ingraham her listeners that she was "beginning to enjoy" the shutdown; she also tweeted out her apparently earnest concern that the closure of a parking lot on federal land meant that "ppl risk their lives pulling off the GW Pkwy".

Fox News has been a funhouse of these distorted twin thoughts, not surprisingly, with guest after guest mocking the seriousness of the shutdown; in a particularly Orwellian stroke, someone at the network even did a search-and-replace on AP stories run on the site, replacing "shutdown" with "slimdown". At the same time, they've given breathless coverage to a highly-selective pool of "slimdown" victims: first, the second world war veterans who faced some inconvenience at the war's memorial, and, more recently privately-funded parks and – incorrectly – the nation's missing-child "Amber Alert" system.

Let's unpack this rhetoric, since it's wholly representative of the coverage that conservative media has given the shutdown. With one side of your head, you need to remember that government is bad, and that the less of it there is, the better. Supporting that thought is the belief that a government "slimdown" won't disrupt any of the government's more important functions.

With the other side of your head, you need to dredge up righteous indignation at the loss of some government functions. It almost doesn't matter which ones, though it's helpful if they are services that strike a sympathetic chord without being, you know, necessary. The right-wing Washington Examiner has some examples to get you started, including "Lake Mead, NV property owners" and "tourists".

Now, try to stand up. Do you feel a little dizzy? Seeing double? You better sit back down.

How is it that so many conservatives seem able to not just stand, but stand for hours and hours and hours holding both these thoughts in their heads? It would be easy to dismiss them as cynics, that perhaps they don't believe either proposition. But as the remarks about "being willing to compromise" caught on a hot mic between Republican Senators Rand Paul and Mitch McConnell show, at least some of their convictions are sincere – maybe especially this part, "I know we don't want to be here, but we're gonna win this, I think."

Conservatives' problem is not so much that these are two ideas with no basis in fact, but that both ideas have some basis in fact.

That government is unpopular is the easy part. There's a long and even somewhat honorable history to that tenet of conservative philosophy. In fact, that's pretty much argument that the leaders of the shutdown strategy made over the summer to skeptical lawmakers and not-so-skeptical Tea Party activists.

There is one important difference between the small-government philosophy as espoused by, say, the Anti-Federalist Papers and the arguments made by the Tea Party Patriots and Heritage Action: the anti-federalists argued from logic, these modern-day PACs used a misleading poll. They asked voters in conservative districts if, "in order to get … Obama to agree to at least have a 'time out'" before implementing the Affordable Care Act, "would you approve or disapprove of a temporary slowdown in non-essential federal government operations, which still left all essential government services running?"

Well, if you put it that way … And, of course, they did put it that way, and found that voters supported a totally painless shutdown by a 2-to-1 margin.

And this gets us to the half-truth behind the outrage at "slimdown targets": however much you dislike the faceless bureaucracy of "the government", there are very few people who truly want to live without the services it provides. The traditional basis for party divisions has been in deciding what services it provides, and to whom. It makes us hypocrites; it makes us human. Most of us don't really try to argue two different philosophies at the same time, we cave to realism and sentiment. We agree to feed the children of poor families and pay for safety regulations to be enforced. We haggle over the small things because sometimes the big ideas are too large to be contained in a single debate, and it's foolish to even try.

F Scott Fitzgerald once called "hold[ing] two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain[ing] the ability to function" the "test of a first-rate intelligence", but when it comes to the GOP, the jury's out on the "functioning" part.

Are Americans dumb? No, it's the inequality, stupid

Are Americans dumb? This is a question that has been debated by philosophers, begrudging foreigners and late night TV talk show hosts for decades. Anyone who has ever watched the Tonight Show's "Jaywalking" segment in which host Jay Leno stops random passersby and asks them rudimentary questions like "What is Julius Caesar famous for?" (Answer: "Um, is it the salad?") might already have made their minds up on this issue. But for those of you who prefer to reserve judgement until definitive proof is on hand, then I'm afraid I have some depressing news. America does indeed have a problem in the smarts department and it appears to be getting worse, not better.

On Tuesday, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released the results of a two-year study in which thousands of adults in 23 countries were tested for their skills in literacy, basic math and technology. The US fared badly in all three fields, ranking somewhere in the middle for literacy but way down at the bottom for technology and math.

This shouldn't be all that surprising as there is a well documented pattern of American school kids failing to keep up with their tiger cub counterparts in other countries. But these results are the first concrete proof that this skill gap is extending well beyond school and into adulthood. The question is, do the study's results imply, as the New York Post so delicately put it, that "US adults are dumber than your average human"? Hardly, but it does suggest that many Americans may not be putting the smarts they have to good use, or, more likely, that they are not getting the opportunity to do so. Put another way: it's inequality, stupid.

Just a quick scan of the countries that fared really well in all three categories (Norway, Sweden, Japan, Finland and the Netherlands) compared to the countries that fared really badly (America and Britain) gives a pretty good indication that the inequality that is rampant in the (allegedly) dumber nations might have something to do with their pitifully low scores. A closer look at the results is also revealing. The incomes of Americans who scored the highest on literacy tests are on average 60% higher than the incomes of Americans with the lowest literacy scores, who were also twice as likely to be unemployed. So broadly speaking, the better off the American, the better they did on the tests.

Now this is just a wild guess, but could this possibly have something to do with the fact that the kind of schools a poor American kid will have access to are likely to be significantly inferior to the kinds of schools wealthier kids get to attend? Or that because of this, a poor kid's chances of getting into a good university, even if she could manage to pay for it, are also severely compromised? And let me go one step further and suggest that the apparent acceleration of America's dumbing down might be directly connected with the country's rising poverty rates.

Before I go on, I should say that even I can see some holes in the above theory. You only have to look at certain members of congress (read Republicans who forced the government to shutdown last week), for instance, many of whom attended some of the finest universities (and make bucket loads of money), to see that even an Ivy League education may be of little use to a person who is simply prone to stupidity. I should add also that many people believe that it's the large immigrant population (of which I'm a member) who are responsible for bringing down the nation's IQ, which further complicates the dumb American narrative. Indeed one could argue all day about the reasons Americans are falling behind, (Woody Allen blames fast food), but we should at least be able to agree on the remedies.

Here's the thing, most economists agree that in this technology driven age, a highly skilled workforce is key to any real economic recovery. It doesn't bode well for the future then that so many American students, particularly low-income and minority students, are graduating high school without basic reading or math skills. Nor does it inspire confidence that students who leave school without basic skills are not acquiring them as adults. So America's alleged dumbness has a lot to do with inadequate schooling for (poor) children and teenagers and a dearth of continuing education opportunities for low-income adults. By contrast, the OECD study found that in (more equal) countries that fared better in the tests, like Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands, more than 60% of the adult population have engaged in continuing education programs or on the job training.

The smart thing to do then surely would be to pour resources into early and continuing education opportunities so that American adults will be equipped with the necessary skills to compete in the global economy. This is where the dumb argument really gets a boost, however, because the opposite is happening. Those same congressional geniuses I alluded to earlier are also responsible for forcing through the cuts known as sequestration, which among other things cut 5% from the federal education budget. Because federal education funding is doled out according to the number of low-income students in a given school, it is poor children, the ones who most need the help, who are being disproportionately impacted by the cuts. Furthermore since 2010, almost $65m, over one-tenth of the entire budget, has been cut from adult education grants.

So are Americans dumb? The answer appears to be yes, some are. The dumb ones are not the poor minorities or low skilled adults who fared badly on the OECD tests, however, but a certain privileged and selfish elite, who have suffered from no want of opportunities themselves, yet seem to think that denying millions of struggling Americans an equal (or indeed any) opportunity to get ahead is a sensible way forward. The results are in now and clearly it isn't. The question is will enough Americans be smart enough to do something about it?

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2013

["Stock Photo: Confused Man Scratching Head" on Shutterstock]

'Breaking Bad' can't be art: Thoughts on the first truly naturalist television narrative

A few weeks after the finale of Lost, Chad Post attempted to defend it by claiming that its nonsense was the stuff of art. "What’s interesting," he argued, "is how these six seasons functioned as ... a great work of art [that] leaves things open to interpretation, poses questions that go unanswered, creates patterns that are maybe meaningful." I'm not interested in discussing the merits of the Lost finale – whether all of the "survivors" Oceanic 815 were dead the entire time or some of them were only dead most of time doesn't matter, as they're both the narrative equivalent of convincing a child you've stolen its nose: it only works because kid's not equipped to know it doesn't.

Defenders of the Lost finale, of course, have no such excuse and are instead forced, like Post, to recapitulate aesthetic theories they half-remember from high school – in this case, the quasi-New Critical theory that elevates the interpreter over the work of art. It's the critic, after all, not the artist, who benefits from "leav[ing] things open to interpretation."

The New Critic was an archeologist of ambiguity, teasing from every contradiction he encountered a paean to the antebellum South. They valued ambiguity as an aesthetic virtue because poems and novels that possessed it could be made to be about anything, which freed them to make statements like, when it came to great works of art, "all tend[ed] to support a Southern way of life against what may be called the American or prevailing way." And they did so by being ambiguous, which allowed the New Critics to say, without irony, that great works of art celebrated "the culture of the soil" in the South. This, dear reader, is the brand of literary and aesthetic theory you were likely taught in high school, and by its druthers, Breaking Bad's not even a work of art, much less a great one.*

In fact, by this standard, it's quite possibly the least artful narrative in the history of American television, and because of this, it's the first show that deserves the label "naturalist." The naturalist novels of the early 20th Century were tendentious in the most base sense of the word: any tendency that appears in characters' personality early in a book will, by its end, have metastasized into impulses so vast and deep you wonder why they even tried to repress them.

For example, in the first chapter of McTeague (1899), Frank Norris compares his titular character to a single-minded "draught horse, immensely strong, stupid, docile, obedient," whose one "dream [was] to have projecting from the corner window [of his "Dental Parlors"] a huge gilded tooth, a molar with enormous prongs, something gorgeous and attractive."

There's your premise: McTeague is dumb and stubborn, especially in the service of his vanity. In the next chapter, when he tries to extract a tooth from the mouth of a patient he's fallen in love with, it's no surprise that "as she lay there, unconscious and helpless, very pretty [and] absolutely without defense ... the animal in [McTeague] stirred and woke; the evil instincts that in him were so close to the surface leaped to life, shouting and clamoring."

"No, by God! No, by God!" he shouts, then adds "No, by God! No, by God!" He tries not to sexually assault her, but fails, "kiss[ing] her, grossly, full on the mouth." Moreover, his failure revealed that "the brute was there [and] from now on he would feel its presence continually; would feel it tugging at its chain, watching its opportunity." When the woman, named Trina, wakes from the procedure, he proposes to her with the same stupid vehemence with which he tried not to assault her:

"Will you? Will you?" said McTeague. "Say, Miss Trina, will you?""What is it? What do you mean?" she cried, confusedly, her words muffled beneath the rubber.

"Will you?" repeated McTeague.

"No, no," she cried, terrified. Then, as she exclaimed, "Oh, I am sick," was suddenly taken with a fit of vomiting.

One of the most prominent features of naturalist prose, as you can see, is stupid, ineffective repetition in the face of adversity. McTeague can shout "No, by God!" as many times as he'd like, but he still assaults her, and no matter how many times Trina says "No, no" in response to his "Will you?" the only way this ends well for either of them is if she vomits all over his office. Given such favorable initial conditions, would it surprise you to learn that after she wins the lottery, he beats her to death? Or that the novel ends with him handcuffed to the dead body of his best friend, who he also beat to death, in Death Valley?

Because McTeague is a naturalist novel, it shouldn't. The key phrase buried in the previous paragraph is "initial conditions," because when you're in the presence of a naturalist narrative, they're all that matter.

By now, I'm sure it's obvious how this relates to Breaking Bad: in a real sense, the second through fifth seasons mark the inevitable, inexorable consequences of what happens when someone with Walter White's character flaws is put in the situation he's put in. Like his forbear McTeague, he's incapable of developing as a character: he can only more robustly embody the worst aspects of his fully-formed personality.

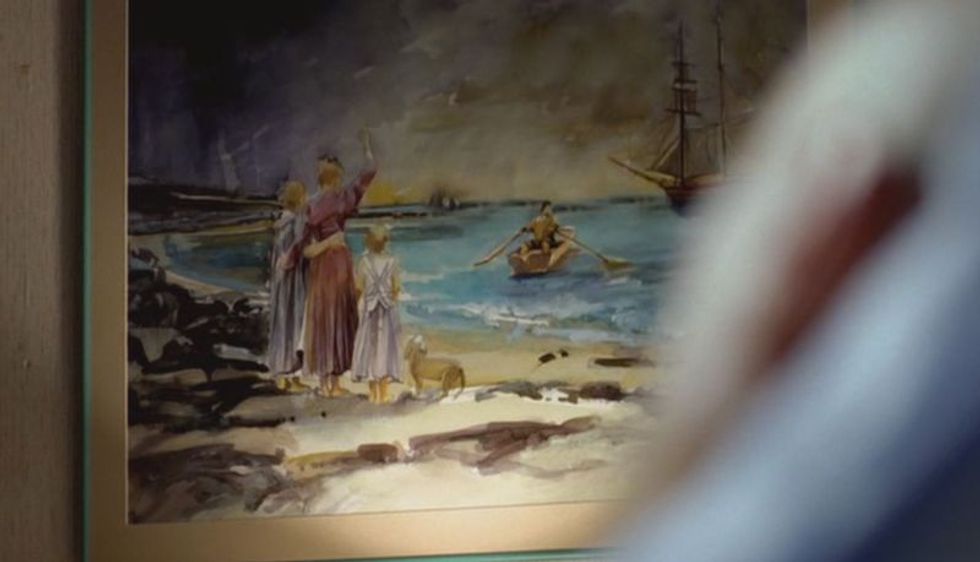

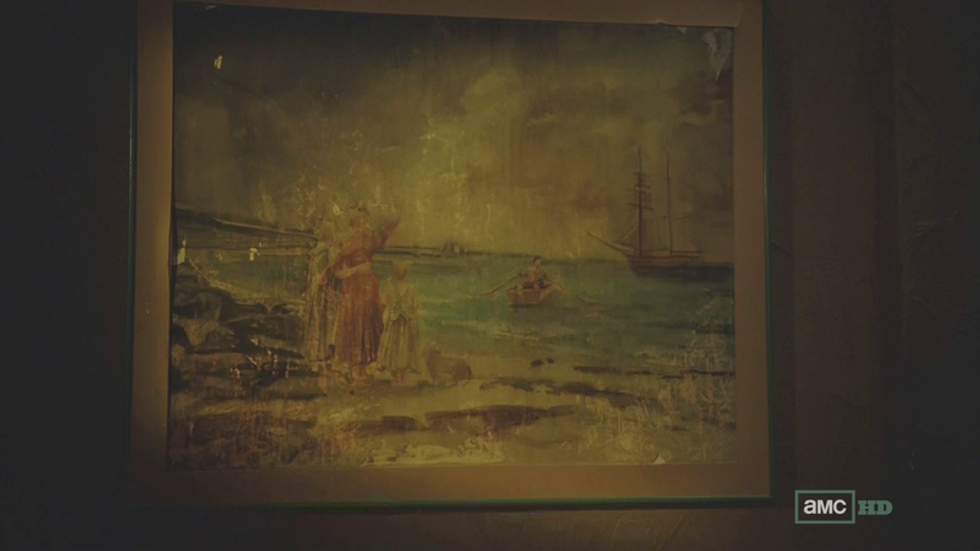

This is why, in naturalist novels and Breaking Bad, repetition is so significant: it's only when provided with a reminder of where the narrative started that we're able to recognize how much the central character hasn't changed. Every time we see another visual echo from episodes past – and in the fifth season, they come fast and frequently – we're reminded of how committed Walter is to his vision of himself as a heroic figure struggling against a universe determined to wrong him. Consider this shot from "Bit by a Dead Bee," the third episode of the second season:

Walter is in his hospital bed after the shoot-out with Tuco in the desert, which happened after he had been missing for three days and, of course, which almost got his brother-in-law Hank killed. He's also claiming that the cancer treatment ate the memory of the walkabout it sent him on. The difference between the man he is – one who's capable of devising a cover story for his meth-related absence that involves playing cancer for sympathy – and the one he imagines himself to be: the one in the boat, about to leave his family alone, possibly defenseless, while he heroically sets out into the great unknown. The next time he sees that image, he's in a motel room surrounded by white supremacists planning the coordinated execution of the remainder of Gus's crew. The director of “Gliding Over All,” Michelle MacLaren, moves our eyes around the scene before settling on a convoluted long shot:

MacLaren is fond of shots in which you're forced to follow eyelines around the frame in order to make sense of the scene, and like that banquet in the “Second Sons” episode of Game of Thrones, it's only after you've done the work of following everyone's eyes around the room that you realize that the most important element in the frame isn't actually in the frame. Once you follow an eyeline to an uninteresting terminus, you move on to the next character, so if you start analyzing the frame from the center and track on action, you'll move to Kenny stretching and follow his eyes (red) to the floor, then Frankie shuffles in place, so you look at him and follow his eyes (blue) to the table, but since that seems unpromising, Todd catches your attention when he shifts his weight, then you follow his eyes (green) to the bed, which means that McClaren's direction has compelled you to move your eyes around the screen until you reach the area of the bed at which Todd's staring, which is puts them right next to Walter, who has remained stock-still throughout. She didn't need him to move or even speak to draw your attention to Walter, she's done so by other means. Once she has you where she wants you, she has you follow his eyeline (yellow) to its terminus, which is off-frame.

Following eyelines to their rainbow's end is a function of film that doesn't necessarily pique our curiosity, but when we come to the end of our journey around the frame and the most significant character in it is staring at something off it, we desperately want to know what he's looking at.** McClaren knows that we'll be less interested in the frame when we find out what he's staring at, so beginning with that long shot (14:43), she cuts to a medium close-up on Jack (15:06), a close-up on Kenny (15:10), a medium shot on Todd (15:13), an extreme close-up on Jack (15:17) that racks to a medium shot on Frankie (15:20) before reversing to the initial medium on Jack (15:23), then back to the initial medium close-up on Jack (15:24) before jumping to a clean medium on Frankie (15:28), then to a more extreme close-up on Jack taking a drag (15:29), then she moves back to the close-up on Kenny (15:31), then back to Jack (15:35), back to Kenny (15:39), and back to Jack (15:41) until finally returning to Walter (15:50), who is of course still staring at something off-frame. McClaren's refused to provide us with the information we desire for more than a minute at this point, but it wasn't a typical minute.

According to the Cinemetics database, the average shot length (ASL) in “Gliding Over All” is 5.8 seconds, but as you can see from above, after that initial 23-second-long shot of Jack, the scene has an ASL of 3.8 seconds.*** Lest you think I'm using the kind of “homer math” that leads sports reporters to write about how their team's ace has the best in ERA in the league if you throw away the four starts in which he got rocked: I'm sequestering this bit of the scene and treating its ASL in isolation because we watch scenes sequentially and in context.

The shift in the pacing of editing created the impression that something really exciting was happening, but “four guys in a motel room talking about doing something exciting” actually qualifies as exciting; the other alternative is that the shot-frequency accelerated because McClaren was building up to something exciting, like the revelation of what Walter is staring at. The editing could be doubling down on the anticipation created by that intial long shot: as frustrating as it is to watch shot after shot fly by without learning what's on that wall, the editing's at least affirming our initial interest in it.

Or was, until she cut to the close-up of Walter staring at the painting (15:50), and because it's a close-up of someone staring at something off-frame, you assume that the next shot will be an eyeline match, but no, MacLaren cuts back to Jack, who's explaining to Walter how murdering ten people is “doable,” but murdering them within a two minute time-frame isn't. In a typical shot/reverse shot situation, especially when it's in the conversational mode as this one is, you expect the eyelines to meet at corresponding locations in successive frames. If Walter's head is on the right side of the frame, and it is, you expect Jack to be looking to the left side of the frame in the reverse, and he does:

The sequence is off-putting because Walter's violating cinematic convention in a way that makes us, as social animals, uncomfortable. On some fundamental level, the refusal to make eye contact is an affront to a person's humanity, so even though Jack's a white supremacist with a penchant for ultra-violence, we feel a little sorry for him. He is, after all, being ignored in favor of we-don't-even-know-yet, but at least it's something significant. MacLaren wouldn't have put all this effort into stoking our interest in something of no consequence, but that doesn't mean we're thrilled when she cuts out to the initial long shot in which whatever-it-is remains off-frame, or when she cuts to an odd reverse on Walter, who asks “Where do you suppose these come from?”

How wonderful is that “these”? We're finally going to learn what Walter's been staring at, but even the dialogue is militating against our interest, providing us with the pronoun when all we want to see is the antecedent. MacLaren holds on Walter for one last agonizing beat before finally reversing to this image of the painting (16:09):

This reverse shot seems more conversational than the last – again, in a way that insults Jack's essential humanity, or whatever passes for it among white supremacists – only now the conversation isn't between Walter and any of the actual human beings sharing that motel room with him, it's with himself.****

“I've seen this one before,” he informs the very people he just insulted. It's not that he's wrong – it is the same painting he saw after he ended up in the hospital, and the timing here is crucial. In “Bit by a Dead Bee,” his outlandish plan had just been successfully completed, so when he looked at the husband heroically rowing out to sea, nobly sacrificing himself for the family he's left behind, he sympathetically identified with a man who shared his current plight, who had made a decision and was following through with it for the sake of those he loved. But in “Gliding Over All,” he sees the same painting before one of his outlandish plans has come to fruition, so now when he sympathizes with the husband heroically rowing out to sea, nobly sacrificing himself for the family he's left behind, he identifies with him because they share a common fate, as both have to decide whether to continue with their foolishness or return to shore.*****

Astute readers may have noticed that I just wrote the same sentence with different words. That's because I did. The only “development” Walter's underwent from the first time he saw that painting to now is that he's more fanatically committed to the image of himself as the hero sacrificing himself for his family. Every sacrifice he makes on his family's behalf only makes him more of the same same kind of hero he's always imagined himself to be.

The presence of this painting – as well as the other visual echoes, most obviously Walter's birthday bacon – reminds us that it's only been eleven months since the moment he first saw it, in November 2009, to the moment he sees it in “Gliding Over All,” in October 2010. Naturalist novels also focused on the rapidity with which can descend in the absence of a social safety net. McTeague's life unravels astonishingly quickly once he loses his job: four months later he and Trina are living in squalor; a month after that, she moves into an elementary school; two months later, he murders her; two months after that, he's chained to the body of a dead man in the middle of Death Valley. Because of the kind of person he is, this is how McTeague's life had to end. Aaron Paul's appearance in Saturday Night Live demonstrates just how much Breaking Bad shares this naturalist concern.

I could go on: the short stories and novels of Jack London were about the opportunities to be had in the wilderness, and the dangers associated with them. In his most famous story, “To Build a Fire,” there is a moment in the fourth paragraph when the nameless protagonist could have, and should have, turned back. Once he makes the decision not to, his fate is sealed, it just takes another 40,000 words to reach it. If there's an art to enjoying a man struggle in vain against his inevitable doom, it's been lost to us – or had been, until Breaking Bad, which demonstrated that there is an audience for naturalist narratives, bleak and unremitting though they may be. Moreover, the opening scene of the finale, “Felina,” almost seems like a combination of “To Build a Fire” and another famous naturalist story, Ambrose Bierce's “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” I'm not saying I believe that Walter dreamed he took his revenge in the moments before he froze to death, but it's not entirely implausible, especially if the series is considered in the light I've presented it here. (Norm MacDonald, of all people, has my back on this.)

The question remains, then, whether Breaking Bad qualifies as "art." Literary naturalism's reputation has faded since the 1930s because, in part, critics consider it more akin to an experiment than literature. Literature requires its characters to develop, to become "round," as they used to say -- whereas naturalists were like scientists who would rather take a personality type and stick it in fifteen different environments so they could observe its behavior. When you consider the conversations that followed George R.R. Martin's comment about Walter being a bigger monster than anyone in Game of Thrones, you can see where that temptation comes from, and how powerful it is, three-thousand comments deep in discussions about whether White would've been more like Tywin Lanister or Roose Bolton.

So is Breaking Bad art? Of course it is. The absurd amount of detail included above isn't meant to overwhelm, merely to acknowledge the level of artistry that went into demonstrating that Walter hasn't grown. I would take it one step further and say that even if you don't believe naturalist narratives can be considered "art," Breaking Bad would still be art, because as much as critics focus on the show's content, what separates it from most television is the manner in which it's presented. Even if the plot itself were terrible, the manner in which it's shot would elevate it to the status of art.

*The main reason New Criticism was adopted as a model was that, unlike the modes of historicism that preceded it, it was infinitely scalable. After the GI Bill was passed, even college and university faculty were worried that their students lacked the educational background required to write the kind of research papers they'd previously assigned, but anyone could be a New Critic: all you had to do was look at a poem and point out what didn't make sense, because that's what it a work of art. Within half a decade, the bug of student ignorance became a feature.

**If you were paying close attention when the scene opened, you would've noticed, since she opens with a medium shot of the painting, then pulling back and sweeping to the right. Like many scenes in Breaking Bad, this one is sequenced backwards, providing us with information before we can understand – or if you've seen “Bit by a Dead Bee” recently, remember – the significance of it.

***For the record: 4 seconds, 3 seconds, 4 seconds, 3 seconds, 3 seconds, 1 second, 4 seconds, 1 second, 2 seconds, 3 seconds, 4 seconds, 4 seconds, 2 seconds, 4 seconds, 4 seconds, 2 seconds, and finally 9 seconds.

****Before you wonder why I'm not just calling that an eyeline match, because it's also one of those, keep in mind that not only has Walter been staring at it with a faraway look in his eyes for almost two-and-a-half minutes, he now appears to be asking it a question. Also, in a move seemingly designed to frustrate my former students, check out the examples the Yale Film Analysis site chooses for “eyeline match” and “shot/reverse shot.

*****The boat seems closer to shore than ship, after all, which only adds to the nobility of the man rowing it out to sea, because it'd be so much easier to just turn around.

[This was originally published at Lawyers, Guns & Money, where Scott Kaufman also writes when he's not chairing the AV Club's Internet Film School.]

'Breaking Bad': A Tragic Gay Love Story

Sunday night's Breaking Bad finale was incredible. It was the first time my sympathy for Walter White outweighed my anger toward him. I teared up when I saw him talk to Skylar for the last time, look at his daughter for the last time and see his son for the last time. And I got really verklempt when Walt rescued his side-kick in distress, freeing Jesse from the clutches of the Aryan Brotherhood, by throwing him to the ground and protecting him the hail of bullets that would ultimately kill everyone except Jesse. How romantic! This is hardly the only scene that lends itself to a homoerotic reading of Breaking Bad. Ladies and gentleman, I present "Breaking Bad: A Tragic Gay Love Story."

Copyright © 2025 Raw Story Media, Inc. PO Box 21050, Washington, D.C. 20009 |

Masthead

|

Privacy Policy

|

Manage Preferences

|

Debug Logs

For corrections contact

corrections@rawstory.com

, for support contact

support@rawstory.com

.