ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Reporting Highlights

- Payments Denied: After a North Carolina man attempted suicide twice, his wife sought coverage for his mental health treatment. His insurance carrier refused to pay for his care.

- Third-Party Reviews: Patients can appeal denials and even ask for additional review by independent physicians. But less than 1 in 10,000 patients eligible for those reviews seek them.

- Medical Necessity: Decisions made by those independent reviewers often turn on the issue of “medical necessity.” Reviewers’ decisions are binding and insurers must abide by them.

The email took Dr. Neal Goldenberg by surprise in a way that few things still do.

As a psychiatrist, he had grown accustomed to seeing patients in their darkest moments. As someone who reviewed insurance denials, he was also well-versed in the arguments that hospitals make to try to overturn an insurer’s decision not to pay for treatment.

But as soon as he opened the review last October, he knew something was different. It was personal and forceful and meticulous — and it would lead him to do something he had never done before.

“Based on the indisputable medical facts, we are unsure why anyone would assert that any part of the insured’s inpatient behavioral health treatment was ‘not medically necessary,’” the appeal letter argued.

The battle playing out on the pages before him began in March of 2024. Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield had refused to pay for a North Carolina man’s monthlong treatment at a psychiatric hospital. The man had been suffering escalating mental health issues, culminating in back-to-back suicide attempts. But using a designation insurers commonly employ when denying coverage, doctors working for Highmark determined the care was not “medically necessary.”

Insurance companies deny hundreds of millions of claims a year, and only a tiny percentage of people appeal them. Even fewer take the process to the very end, appealing to a third-party, or external, reviewer like Goldenberg. A recent report found that, on average, less than 1 out of every 10,000 people eligible for an external review actually requested one.

Goldenberg, who is based in Cleveland, had initially picked up the extra job a few years ago to help pay down the massive student debt he and his wife, a family doctor, had accumulated during medical school.

External reviewers like Dr. Neal Goldenberg have the power to overrule an insurer’s decision to deny coverage for patient care and to force insurance companies to pay for treatment.

External reviewers like Dr. Neal Goldenberg have the power to overrule an insurer’s decision to deny coverage for patient care and to force insurance companies to pay for treatment.In that role, he has the power to overrule an insurer’s decision to deny a patient coverage and force the company to pay for treatment. Few things anger him as much as patients being denied the care they needed, which compelled him to continue doing the reviews even after the student loans were paid off.

Attached to the appeal letter were nearly 200 pages of records organized by headings and numbers. There was even a glossary of diagnosis codes that are used for billing.

Goldenberg’s first thought was that a lawyer had put together the appeal. But the name on the bottom of the letter didn’t belong to a law firm.

He spent the next hour and a half reading the file: records from eight separate medical providers; research on suicidal ideation; letters from two psychiatrists supporting the appeal, including one that described the patient’s depression and stress as causing “psychological suffering and functional impact.”

Then he did something he hadn’t done in the six years he’s been reviewing cases. He called the name at the bottom of the letter: Teressa Sutton-Schulman.

The line rang several times before going to voicemail.

“Hello. My name is Neal Goldenberg. I am reviewing an insurance claim for your husband,” he began.

Teressa Sutton-Schulman and her husband on their wedding day

Teressa Sutton-Schulman and her husband on their wedding daySutton-Schulman’s husband, who ProPublica is identifying by his middle initial “L,” had always been anxious and more than a little obsessive. As an adult, financial matters, especially, threw him into a panic and eventually sent him to therapy.

By January of last year, after deciding that the therapy wasn’t working, he made an appointment with his primary care doctor, who prescribed him an antidepressant and antianxiety medication. After a few days, L called the doctor to say he felt worse. A panic attack landed him in the emergency room about a week later.

Right before Valentine’s Day, he met with a psychiatrist.

The way his mind had begun to shuffle through worst-case scenarios was something Sutton-Schulman hadn’t witnessed before.

They met at Georgia Tech. L had noticed her at a party. When he walked up to her, she told him she was waiting for someone.

“I could be someone,” he responded without missing a beat.

She was drawn to his humor and charm. As an introvert, Sutton-Schulman marveled at the way his presence filled a room, floating between people and the things they talked about with ease. He considered her his rock, his best friend, the person he loved most in this world.

They shared a mutual admiration for each other’s intellect and drive. He skewed nerdy, playing Dungeons & Dragons in his downtime. Not that he had much. As a rising star in the world of software engineering, work consumed him. He craved success the same way he pushed the boundaries of technology — relentlessly.

They decided not to have kids; they had each other and their work. In the early 2000s, they built a software consulting company together. Although Sutton-Schulman trained as a chemist, she went back to school to become a paralegal and the company’s in-house legal expert.

More than 20 years into their marriage, they still held hands like it was their first date. When they entered their 50s and faced the prospect of growing old in their three-story house, they decided to buy a ranch home in the same small North Carolina town outside of Raleigh that they had lived in for more than two decades.

That decision would forever alter their lives.

After more than 20 years of marriage, Sutton-Schulman and L bought a ranch home outside of Raleigh, North Carolina.

After more than 20 years of marriage, Sutton-Schulman and L bought a ranch home outside of Raleigh, North Carolina.The pandemic’s housing market, with its skyrocketing prices and houses that sold before they even went on the market, exacerbated his stress. The couple put offers on half a dozen houses. They lost $25,000 in earnest money after backing out of the only two offers that were accepted. The hit hurt, but thanks to L’s job, they had more than enough in the bank.

Finally, in the summer of 2023, they found their house, though it needed some work. They decided to rent out their old house, but that, too, required some fixing up before they could put it on the market. L was determined to get a renter in quickly, and they poured money into both houses simultaneously.

L’s anxiety grew with every expense. They argued about money, about his insistence on undertaking everything at once, about his unwillingness to get treatment, about their five cats. She begged him to get help. He assured her he had it all under control.

After two months, they moved into the new house.

L grew more irrational each day. All he could do was fixate on the finances. On top of it all, they weren’t sleeping. To help with the cats’ transition to the new house, Sutton-Schulman had talked to L about getting them an enclosed space on their patio. But L, who was overseeing the remodeling, didn’t prioritize it. The cats kept them up each night with their incessant whining and scratching at their doors.

She knew that all of his concerns were symptoms of a larger problem, but neglecting to take care of the cats was the final straw. As hard as it was for her to leave him, she felt like she had no other choice. Two weeks after moving in, she packed her bags and her SUV and moved back into their old house.

It took her leaving for him to see a therapist and agree to couple’s counseling.

Buying the house, he told his wife, was a mistake.

If you or someone you know needs help, here are a few resources:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

“I started catastrophizing every day,” L said at his appointment with his psychiatrist right before Valentine’s Day, medical records show.

L told him that he regularly woke up at 2:30 a.m. in the throes of a nightmare. His heart raced. His legs felt weak. He contemplated ending his life.

The psychiatrist tried to determine how serious his suicidal thoughts were. L admitted he felt anxious and hopeless, but he said he was afraid to die.

“I’m a fucking coward and I can’t do it,” L told the psychiatrist, according to his medical records. “I don’t know how to kill myself.”

Two days later, he swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills and chased them down with bourbon. He slid into the driver’s seat of his Mercedes parked in the garage, turned on the ignition and closed his eyes.

L finally agreed to go to counseling after Sutton-Schulman moved out, but his condition continued to deteriorate.

L finally agreed to go to counseling after Sutton-Schulman moved out, but his condition continued to deteriorate.Goldenberg’s path to medicine began at a young age. He excelled in science in school. He grew up with a dad who was a dentist and a belief that doctors could heal.

But 2003, his first year of medical school, was difficult. He didn’t fit in with some of his classmates who were focused on which speciality would yield the biggest salary.

Stumbling upon a book by Dr. Hunter “Patch” Adams, the doctor who devoted himself to infusing humor and compassion in medicine, provided the inspiration he needed. Adams’ name became the title of a movie starring Robin Williams, which made the red clown nose he popped on when visiting sick children famous.

Goldenberg reached out to Adams’ nonprofit Gesundheit Institute, which allowed him to volunteer. He soon embarked on a 300-mile bike ride from Ohio to West Virginia to spend the summer after his first year of medical school surrounded by people who, like him, were frustrated by the health care system. They yearned for an approach that focused not just on the illness of one patient, but on the health of a community.

When he got back, he volunteered at a free clinic in Columbus. The experience deepened his appreciation for caring for the sick as well as his disillusionment with a health care system he viewed as farming out the medical treatment of certain patients to trainees.

The next turning point came when he attended a conference of the American Medical Student Association, which encourages doctors to advocate for affordable health care. Seeing so many of his fellow medical students with the same values energized him.

“Vast swaths of our population were uninsured,” he recalled. “I just couldn’t get over how unfair that was and wanted to be part of the good guys fighting to change that.”

“Vast swaths of our population were uninsured,” recalled Goldenberg. “I just couldn’t get over how unfair that was and wanted to be part of the good guys fighting to change that.”

“Vast swaths of our population were uninsured,” recalled Goldenberg. “I just couldn’t get over how unfair that was and wanted to be part of the good guys fighting to change that.”Goldenberg met his wife at the conference; together they pledged to improve how medicine is practiced. They both pursued family medicine. But during his residency at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he fell in love with psychiatry. He found satisfaction in building relationships with patients struggling with mental illness and helping them through it.

Madison had pioneered a team-based model in the 1970s that treated patients with severe mental illness in their homes and communities, rather than at institutions and hospitals. He was so struck by this approach that he specialized in community psychiatry. Later, he became medical director of a nonprofit organization that treated the homeless.

The job reviewing health insurance denials came about after he spotted an online job posting.

With more than 15 years’ experience treating patients at clinics and in hospitals, he was flush with knowledge and a desire to make a greater impact. He told himself that he could walk away at any point if he felt he wasn’t living up to the ethical standards he set for himself. He was determined not to be a rubber stamp for anyone — not for the insurance companies and not for the hospitals.

Perhaps surprisingly, he estimates that he sided with insurance companies about half the time. Some hospitals, he said, admitted patients when they didn’t need to, and some doctors wrote that they had ordered treatments that made little sense given the patient’s diagnosis.

The bulk of his cases are reviews involving the major Medicaid plans in Ohio. The third-party company he worked for approached him in 2023 with another opportunity: to do more in-depth external reviews for commercial insurers. He agreed, but his priority remained his main psychiatry job and the patients he treated there.

The third-party review company that Goldenberg works for declined to comment.

State and federal regulations designed external reviews as an attempt to level the playing field between behemoth insurance companies and individual patients. The idea is to provide an added measure that prevents insurers from having the final say in deciding whether they will pay for a claim they had already denied. The Affordable Care Act in 2010 expanded access to the reviews, but barriers regularly get in the way of the process serving as a true check on insurers.

Most people haven’t heard of external reviews, and most denials are not eligible for one. Those that are eligible typically involve medical judgment, surprise medical bills, or an insurer deciding to retroactively cancel or discontinue coverage or determining that a treatment was experimental. Even then, insurers can argue that a denial is ineligible for an external review.

Only after the internal appeals with the insurer are exhausted is an external review an option for some denials. Requests have to be filed within a certain time frame, depending on whether they’re filed under state or federal laws. That distinction can also determine if insurance plans get to pick the company that does the external review.

In addition, it’s nearly impossible to know how effective they are. Insurance companies almost never release data around denials in general. That’s especially true about external reviews.

A recent KFF report looking at federal insurance marketplace plans found that fewer than 1% of of the system’s tens of millions of denials were appealed internally. Of that 1%, about 3% of all upheld internal appeals — only about 5,000 enrollees — went on to file external reviews, though there wasn’t enough data to calculate the rate at which external appeals were upheld.

After L’s suicide attempt last February, a judge ordered him to be committed to a mental health center about 40 minutes south of Raleigh. There, staff took away his phone, shoes and anything that could be a safety hazard. Doctors increased the dosage of his new antidepressant and, while they waited for the medicine to take effect, L spent his days coloring, making bracelets and watching a documentary about meditation.

The court rescinded the involuntary commitment order about a week later, but did so under two conditions: that L be released to his wife’s care and that he see a therapist and a psychiatrist. Sutton-Schulman heeded the judge’s orders and agreed to have him move back in with her.

When she picked him up, they both cried.

“I never want to do anything ever to go back to a place like that again,” he said as he climbed into her car.

At the house, she didn’t let her emotions show through the reassuring facade she maintained for him. Secretly, she was terrified he would try to kill himself again.

Four days later, she woke up to a quiet house. She assumed he’d gone for a walk, as he usually did.

After L’s first suicide attempt, he moved back in with Sutton-Schulman, who agreed to help care for him as a condition of his release from a mental health facility.

After L’s first suicide attempt, he moved back in with Sutton-Schulman, who agreed to help care for him as a condition of his release from a mental health facility.She heard the front door open and went to greet him. Her eyes immediately found him leaning over the kitchen sink. As she got closer, she glimpsed a knife in the sink covered in blood. Then she saw blood pouring out of his neck, spilling from his wrists, soaking his sweater.

She grabbed a towel to put pressure on the gash on his neck.

“Did you do this to yourself?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said.

For the second time in 11 days, she called 911.

“Just let me die,” he said over and over.

Paramedics rushed him to the hospital. This time, police taped off the house and questioned Sutton-Schulman for two hours until a detective got a call from the hospital confirming that L had attempted suicide in the woods behind the house.

By the time she arrived at the hospital, the bleeding was under control. After the doctor stitched up L’s neck and bandaged his wrists, he agreed to accept treatment. Police drove him to Triangle Springs, a residential treatment facility in nearby Raleigh.

But instead of improving, L’s mental health deteriorated. He began displaying signs of psychosis. He told the doctors that “the coke machine was fuzzy and he could hear just random voices,” his medical records show. During a call with Sutton-Schulman, he told her that he believed the other patients had been planted at the facility by the FBI and authorities were trying to frame him for murder.

“Patient is not considered safe to be discharged,” his doctors wrote in his medical notes on four separate occasions.

Desperate, Sutton-Schulman called a friend who is a social worker in psychiatric hospitals. He’s getting worse, she told her. Where else can I take him?

Of the three facilities her friend recommended, The Menninger Clinic in Houston was the only one that returned her call.

She wasn’t sure she could get him there in his condition, but she knew she had to try. She booked an early-morning flight for the two of them. At one point, he dropped to the airport floor. “I can’t do it anymore,” he told her.

“You have to,” she told him.

She was relieved when they arrived at Menninger. The staff did genetic testing that revealed he could have an adverse reaction to the antidepressant his doctor had put him on. Learning that, she said, felt like the missing piece of a puzzle.

Sutton-Schulman got L settled in, met with his doctors and, for the first time in months, felt some hope.

Goldenberg approached his side job with caution.

When he’d started, a part of him feared he would be pressured to side with insurers regardless of the medical evidence. But that didn’t happen. He soon embraced the job as a way to hold everyone accountable because it wasn’t just insurance companies that tried to game the system.

“Doing these chart reviews has also opened my eyes to the way doctors and hospitals cheat the system, even Medicaid,” he said. “And I don’t like that either.”

Over the years, he said, he’s done hundreds of Medicaid reviews and about a dozen external reviews. He knows more than most that no one is immune to having a mental health episode.

“We all have vulnerabilities, and we all have genetic predispositions, sensitivities to certain kinds of stress,” he said. “Someone who’s been able to handle stuff all their life, if they have just too many things going on, it can push you past your breaking point.”

It’s a bit like how a healthy person can be diagnosed with cancer or get into a car accident. People pay for insurance, he said, so it’s not financially disastrous when that happens.

“I’m working within a system that I know is broken, but doing my best to change it from the inside,” he said.

A part of him wonders if Patch Adams would consider him a sellout for not living up to the radical ideologies of his youth. But his goals haven’t changed. They’re evident in the practice philosophy he spotlights at the top of his CV: “Increase quality of life for those suffering from mental illness in an atmosphere of respect, understanding, and collaboration.”

The spirit of his work, which earned him a humanism in medicine scholarship in medical school, is what prompted him to call Sutton-Schulman.

“I see how opaque the system can be,” Goldenberg said, “how frustrating it is when you feel like no one hears you.”

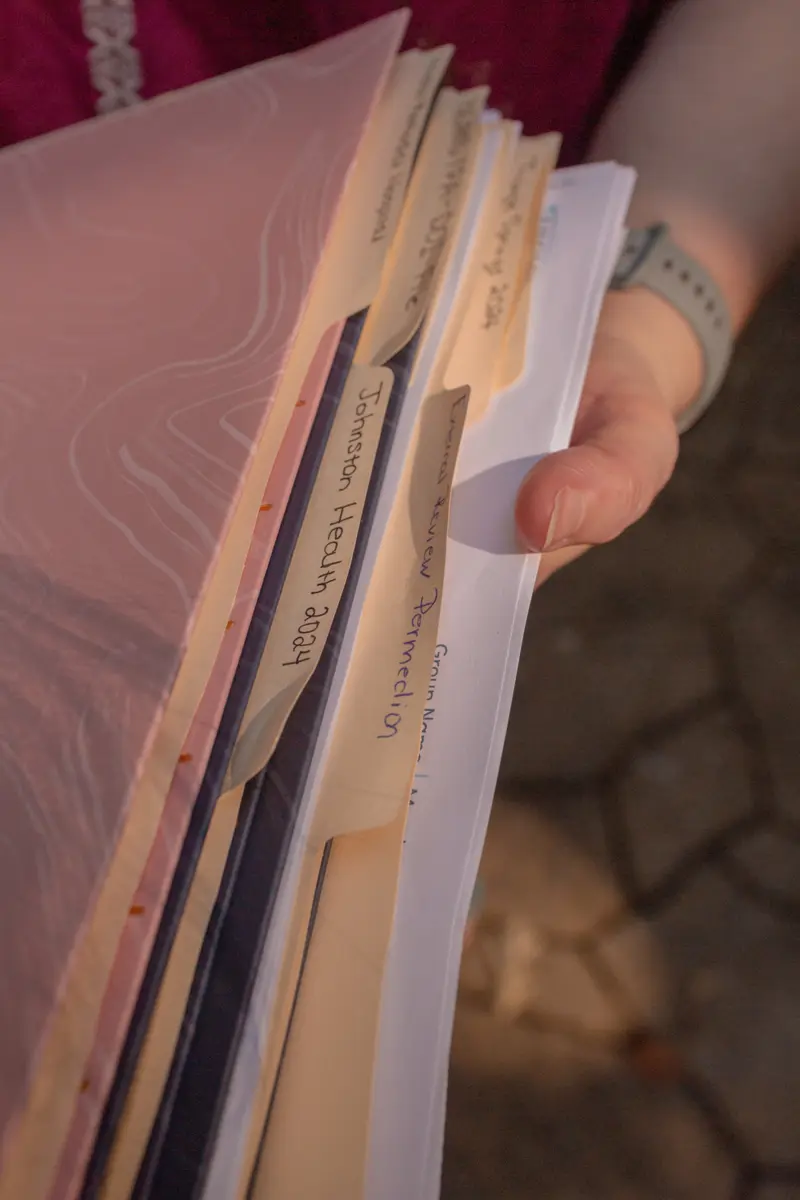

Sutton-Schulman with the records she kept from her husband’s case

Sutton-Schulman with the records she kept from her husband’s caseOn March 19, just a week after her husband was admitted to Menninger, Sutton-Schulman received the first denial from Highmark.

Highmark had sent her a letter in late February confirming pre-authorization for his treatment at Triangle Springs, where L was first treated after his initial suicide attempt. “This approval means that we confirm that the requested services or supplies are medically necessary and appropriate.”

And again a few days later, it sent her another: “We approved the request to extend an inpatient admission for the patient.”

But on that day in mid-March, Highmark showed a balance of $30,599.69.

The reason? The Triangle Springs treatment was not being covered after all; it had been deemed not medically necessary.

The pre-authorization letters included a line saying payment was not guaranteed, but Sutton-Schulman didn’t think much of it. And with good reason. At the top of the letter, in bold, were the words: “We approved your inpatient admission request.” She felt like Highmark was reversing itself.

Sutton-Schulman watched as her husband — one of the smartest men she knew — continued to unravel. When a person is gravely ill, they’re often forced to fight two battles, one against their sickness and the other against the insurance company. As L focused on his health, Sutton-Schulman mobilized against Highmark.

Find Out Why Your Health Insurer Denied Your Claim

Find Out Why Your Health Insurer Denied Your ClaimShe was no stranger to taking on powerful companies. She was part of the army of women who took on the pharmaceutical giant Bayer after they blamed the company’s permanently implanted birth control device for serious health complications. They filed reports with the Food and Drug Administration over adverse reactions, they organized protests, and many of them sued Bayer, though Sutton-Schulman did not.

At the end of 2018, Bayer stopped selling the device, despite insisting it was safe.

In her fight with Highmark, Sutton-Schulman leaned on her paralegal skills, beginning with reading the company’s coverage booklet from start to finish. That’s where she learned of the possibility of the external review. Then she began tracking and documenting everything — the calls with Highmark, its promises, denial letters, bills and appeal requests — and developing her own filing system of labeled manila folders and document boxes. She even started recording her phone calls with the company.

Just as she started to get going, a call from Menninger stopped her in her tracks.

Her husband had passed out in the bathroom and hit his head. Menninger took him to a nearby hospital, where he was treated for a severe colon infection, likely brought on by his long-term use of antibiotics to treat the neck wound.

Once doctors cleared out the infection, an ambulance took him back to Menninger to complete his treatment.

Meanwhile, Highmark sent Sutton-Schulman a succession of denials.

Sutton-Schulman continued to fight Highmark to cover her husband’s care, even as he was hospitalized.

Sutton-Schulman continued to fight Highmark to cover her husband’s care, even as he was hospitalized.Highmark refused to pay for the emergency medical treatment for the colon infection. In a bizarre twist, that denial letter listed her husband as the patient but made reference to the care of a newborn, not that of a 52-year-old man having a mental health crisis.

“It was determined,” the letter said, “that your newborn does not meet the criteria for coverage of an inpatient hospital admission.”

“This is when I really start to think they’re just denying,” she recalled. “They’re not even looking. They’re just ‘deny, deny, deny.’”

A denial letter from Highmark relating to L’s stay in a Texas hospital with a colon infection described the 52-year-old man as a newborn, stating “it was determined that your newborn does not meet the criteria for coverage of an inpatient hospital admission.” Credit:Obtained and highlighted by ProPublica

A denial letter from Highmark relating to L’s stay in a Texas hospital with a colon infection described the 52-year-old man as a newborn, stating “it was determined that your newborn does not meet the criteria for coverage of an inpatient hospital admission.” Credit:Obtained and highlighted by ProPublicaBefore she could appeal it, she was hit with another denial. The company denied her husband’s first week of care at Menninger.

Then the fourth denial arrived, this one for the rest of the treatment at Menninger.

Doctors at the hospital where her husband was treated for the colon infection had persuaded Highmark to pay for the medical care, but she was responsible for the remainder of the appeals. She soon found herself raging at what she came to believe was “weaponized incompetence.”

Fax numbers were wrong. Key records that included the billing codes and denial reasons that she needed for her appeals were no longer available online. The insurer wouldn’t even give her access to her husband’s medical records, though he had signed a release granting her permission.

“At this time,” she wrote to the insurer, “I can only interpret Highmark’s refusal to respond to appeal requests in a timely manner or provide information as an ongoing, purposeful effort to erect insurmountable obstacles to this process.”

On her 18th call to Highmark, she bristled at the notion that a critical letter from the insurer was lost in the mail.

“I never got a letter,” Sutton-Schulman shot back from her kitchen table.

Listen to One of Sutton-Schulman’s Calls With Highmark

Sutton-Schulman: So it’s up to me to do the appeal, to handle the appeal. Which it’s very hard for me to do when there are roadblocks being purposefully erected for me, such as not being notified that I have a case number and that I’m supposed to send stuff in and I’m on a deadline. Because I absolutely would have sent that stuff in. I have it.

Highmark representative: Mm-hmm.

Sutton-Schulman: I am very curious under what scenario exactly a person who has tried to kill himself twice within the span of a week is denied an inpatient behavioral health treatment when every doctor that saw him said he needs to be in a residential treatment program. I am infinitely curious what credentialed individual made that decision that that is not medically necessary.

Highmark representative: Yeah, I definitely understand. That’s very frustrating.

Appalled, she filed two complaints with the state insurance department in Pennsylvania, where Highmark is based. The first, in June 2024, explained the multiple roadblocks she experienced and wrote that Highmark denied claims as medically unnecessary and impeded her ability to appeal them. The department wrote back and incorrectly stated that the denial was not eligible for an external review because it did not involve medical judgment or rescission of coverage.

Six months later, Sutton-Schulman filed a second complaint with the agency highlighting a litany of additional problems and asking for an investigation into Highmark. After both complaints were closed, Sutton-Schulman wrote the agency again, reasserting the “weaponized incompetence” claim and adding that she believed the company’s goal “seems to be not paying claims or to delay payments as long as possible.”

“Frankly,” she concluded, “I don’t even know why they are allowed to continue operating like this without sanctions or fines.”

A spokesperson for the insurance department did not answer ProPublica’s questions, saying that state law prohibits the department from disclosing details of individual consumer complaints or ongoing investigations.

In a statement, the department said every complaint is “carefully reviewed and informs our broader oversight. When we find systemic issues, we have not hesitated to act, including imposing fines, ordering corrective actions, and requiring restitution to Pennsylvanians.”

The Pennsylvania agency and the Delaware Department of Insurance have fined Highmark and its health insurance subsidiaries at least four times in the past 10 years, including as recently as 2024 and 2023. The fines were levied for denying and failing to pay claims on time, including those for mental-health-related treatment. Just last year, Delaware fined Highmark $329,000 for violating mental health parity laws, which aim to ensure that mental health and physical health insurance claims are treated equally. Highmark said in response that it evaluated its practices and ensured that the same standards are used for mental health as physical health. In addition, it said at the time that it would review and revise its procedures where necessary to ensure compliance with state and federal requirements.

L provided Highmark two signed releases authorizing the company to respond to ProPublica, which the company said were necessary for it to answer questions. He also called the company to ask it to respond. Still, Highmark would not discuss L’s case in any detail, citing patient privacy.

Instead, the company provided a statement acknowledging “small errors made by physicians and/or members can lead to delays and initial denials,” but said those are corrected on appeals. The statement said company officials “recognize and sincerely regret” when prior authorization and claims processing are “challenging and frustrating,” and added that the issues raised by L’s case were “resolved at least a year ago.”

The statement said prior authorization requests are reviewed by licensed physicians and completed based on widely accepted national guidelines. The decision to deny or uphold an appeal, the statement said, is based on the same national guidelines. Highmark said it is working to improve its prior authorization process, including reducing “denials when errors are made, regardless of who or how the errors are made because we are passionate about providing appropriate and timely care to our members.”

“Highmark is dedicated to full compliance with all applicable state and federal Mental Health Parity laws regarding coverage for behavioral health services for our members,” the statement said.

In the end, Sutton-Schulman won the Triangle Springs appeal, but Highmark classified L’s treatment at Menninger as two separate admissions. She eventually was able to get Highmark to pay for the first week at Menninger — more than $20,000 — but the company wouldn’t budge on the $70,000-plus for the other four weeks of treatment.

Her final shot was an external review, but getting Highmark to agree to one wasn’t easy — though Sutton-Schulman believed they were eligible. When she finally convinced the company, it gave her less than two hours to file a request before a 5 p.m. deadline. She pressed send on the email at 4:34 p.m.

By the time Sutton-Schulman’s letter landed in Goldenberg’s inbox, he had done enough reviews to know what to expect. But the details of L’s case were striking.

“This is the high-risk case that psychiatrists have nightmares about,” he recalls thinking.

It was also the first time he had received an appeal from a family member, not a hospital. He wondered if he should call Sutton-Schulman. He decided that for a doctor who believes so adamantly in humanism in medicine, this was a chance to be human.

She wasn’t sure what to make of his voicemail. A part of her was relieved, but a bigger part didn’t trust it. After all the denials and broken promises, she couldn’t believe that it could all be resolved in a single phone call.

A little while later, Goldenberg called her again. This time she answered.

He asked how her husband was doing. Did he survive?

He’s back home, she said, seeing a local psychiatrist. “I think they finally have his medication correct and stabilized.”

“I just want you to know that there was a human in this whole process that actually took a look at all this stuff, that actually read it,” he told her. “It probably just felt like that has not been the case for most of it.”

“We all have vulnerabilities, and we all have genetic predispositions, sensitivities to certain kinds of stress,” said Goldenberg. “Someone who’s been able to handle stuff all their life, if they have just too many things going on, it can push you past your breaking point.”

“We all have vulnerabilities, and we all have genetic predispositions, sensitivities to certain kinds of stress,” said Goldenberg. “Someone who’s been able to handle stuff all their life, if they have just too many things going on, it can push you past your breaking point.”He acknowledged that he probably shouldn’t be talking to her.

“Part of the reason I do this job is to make sure that people get what they need,” he said, “and bad doctors get punished, and shitty insurance companies don’t get to do this kind of stuff to people.”

In response to Highmark’s denial, Goldenberg wrote that the insurer did not understand L’s “complex psychiatric and medical situation.” His treatment was interrupted by a medical emergency — he didn’t leave the facility because he had completed treatment, as the company suggested. After doctors tended to the infection, his “psychosis and depression were still severe.” The resumed treatment, he wrote, was “denied unfairly.”

In total, L’s treatment cost more than $220,000, which includes claims that Highmark approved when they were initially filed. But Sutton-Schulman and L had to pay more than $95,000 out of pocket, burning through their savings in hopes that Highmark would reconsider their denials. Many people don’t have the money to pay for care if their insurance won’t cover it. Highmark ended up reimbursing them more than $70,000. Considering out-of-network and other charges, Sutton-Schulman was content with that amount.

With their struggles against Highmark behind them, Sutton-Schulman and L are still putting their lives back together. In July, they returned to couple’s counseling; the therapist told Sutton-Schulman she needed to process the trauma of what happened.

“I’m just now starting to do that,” she said, “because I finally feel like I don’t have any insurance to fight.”

She’s also dealing with her own guilt, wondering if moving out pushed her husband over the edge.

L turned to look at her. “You shouldn’t blame yourself.”

“I know,” she said, her voice breaking. “But the reality of knowing that intellectually to be true, and then emotionally, those are two very different things.”

He has tried to assure his wife that he’s better. He’s returned to work, though colleagues don’t know what happened, other than that a medical emergency kept him away. He logs onto meetings from his laptop and travels for business trips. His voice is exuberant, especially when cracking jokes.

“When your mind shatters like this, it’s hard to explain,” he said. “Nothing makes sense, and you just want it to be over.“

Things feel normal until he catches sight of the scar on his neck. It’s small and could pass as a nick from a razor. But every time he looks in the mirror, he is transported back to that moment in the woods. He’s not sure he can handle the world knowing what happened.

The couple still live in separate houses but eat dinner together most nights. On a recent evening, they sat at the round kitchen table where Sutton-Schulman had done so much of the work fighting with Highmark. He chatted about work. She talked about needing to take one of the cats to the vet. As he got up to leave, she walked him to the door and wrapped her arms around him before saying goodbye.

They recognize how lucky they were that their case was assigned to Goldenberg.

The praise makes Goldenberg uncomfortable.

“It shouldn’t even be a big deal,” he said. “It should have happened multiple steps before it got to me.”

Since the review, Goldenberg has gone back to the residents he teaches. As doctors, he tells them, they have the power to make patients feel seen, to spend an extra few minutes filling out paperwork to help someone with a request for time off work, to support an appeal if they believe an insurer wrongly denied coverage.

“Sometimes,” he said, “there’s an opportunity to reach out and connect in a way that adds a little bit of humanity to the world.”