Derek Williams, 51, has been spending a lot of time thinking about certain numbers.

He committed 12 armed robberies in and around Milwaukee 30 years ago. In 1997, the North Side native was sentenced to 15 years in prison for each robbery – a total of 180 years.

In 2023, a Milwaukee County judge cut that sentence in half after Williams stopped an attack of a correctional officer who was being stabbed with a sharpened pen. The reduction in his sentence made Williams eligible for parole.

But Williams, who was transferred to Sturtevant Transitional Facility from Oakhill Correctional Institution in September, has learned that parole eligibility is not the same as being released. Now, he worries about another number – how many days he will have to wait to go home to his family.

“I’m seeing a parole process that really has no clear path on what a person’s supposed to do,” Williams said. “They create an ideal, and at every turn it’s another road going left or right.”

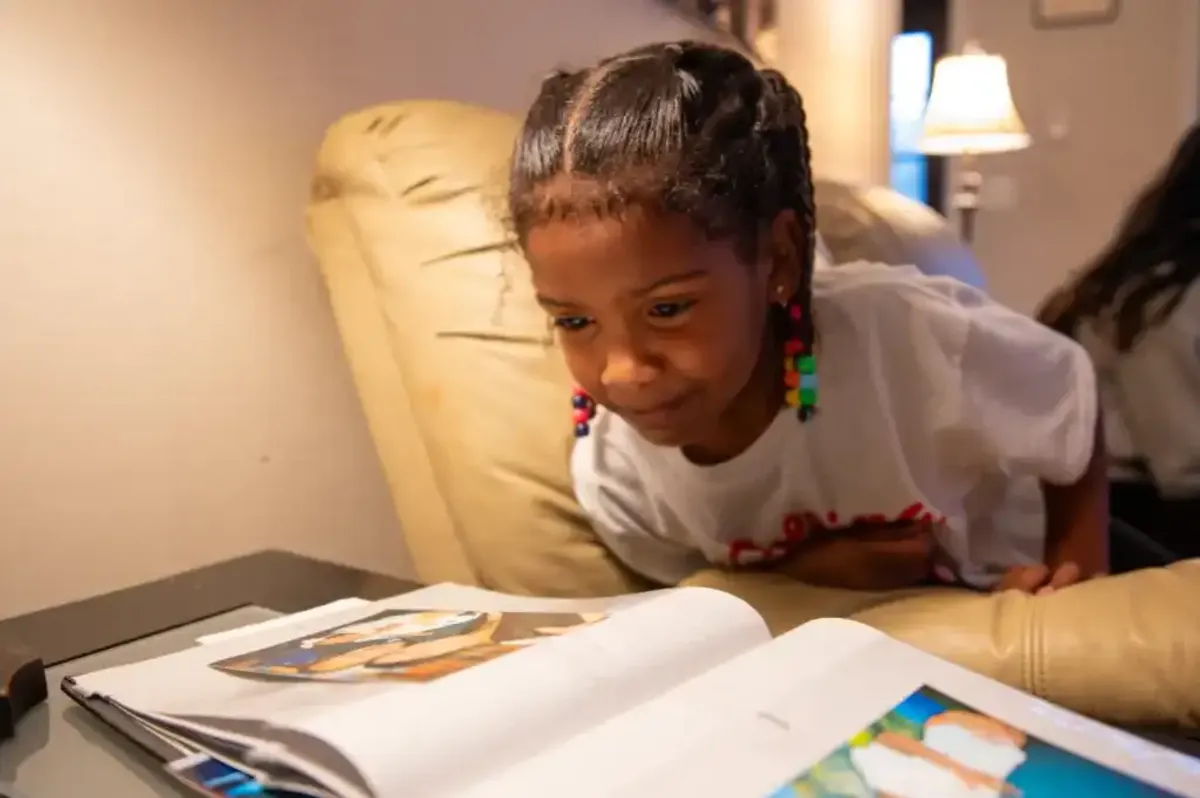

Rikki Williams shows her granddaughter Skylar Valentine, age 6, photographs of Derek Williams. Rikki talks with Derek every day that she is not allowed to visit him in person. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)

Rikki Williams shows her granddaughter Skylar Valentine, age 6, photographs of Derek Williams. Rikki talks with Derek every day that she is not allowed to visit him in person. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local) Skylar Valentine, the granddaughter of Derek Williams, looks at photographs of the two of them. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight)

Skylar Valentine, the granddaughter of Derek Williams, looks at photographs of the two of them. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight)Frustrations with the parole process

In Wisconsin, only people who committed their crimes before Dec. 31, 1999, can become eligible for parole.

Those sentenced for crimes committed on or after Jan. 1, 2000, fall under 1997 Wisconsin Act 283, more commonly known as the Truth-in-Sentencing law. These people must serve the entirety of their prison sentence.

Those sentenced before Truth-in-Sentencing took effect become eligible for parole after serving one-quarter of their prison sentence or after reaching their mandatory release date, whichever comes first.

Before Williams’ sentence was reduced, he would have been eligible for parole in 2042.

Since his sentence reduction in 2023, Williams has gone before the Wisconsin Parole Commission twice – in May 2024 and June 2025.

Both times, the commission said he wasn’t ready for release.

State regulation requires the Parole Commission to consider several factors when deciding whether to grant release: acceptable conduct in prison; completion of required programming; reduction of risk to the public; sufficient time served so release does not depreciate the seriousness of the crime; and an approved release plan.

For both of his parole hearings, the Parole Commission said Williams’ conduct and participation in programming were adequate.

Yet both times the commission deferred Williams’ parole to be reconsidered at some later date. The commission cited an “unreasonable risk to the public” and said Williams had “not served sufficient time for punishment.”

Williams said he doesn’t understand how the commission arrived at these conclusions, especially after the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office and the judge who modified his sentence reduction said he had already served enough time.

“In terms of the armed robberies themselves, we were most acutely concerned with the level of violence,” said Paul Dedinsky, an assistant district attorney for Milwaukee County, during the sentence modification hearing. “I found them to all be extremely serious and necessitating an enormous amount of incarceration, but we believe that end has been met.”

Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Jack Davila agreed.

Williams’ frustration with the parole process is not surprising, said Laura Yurs, a Remington legal fellow at the University of Wisconsin Law School.

“Because parole release is discretionary, it is impossible to predict and tends not to operate as a standardized set of steps,” Yurs said. “For example, what is deemed ‘sufficient time for punishment’ can vary widely from person to person – even when the crime of conviction is the same.”

Parole trends

In recent years, fewer people in Wisconsin are being granted parole, according to Department of Corrections data.

Publicly available charts from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections depict trends in parole hearings, grants, deferrals and denials. The number of people granted parole in Wisconsin has increased since last year but has decreased overall since 2017. (Source: Wisconsin Department of Corrections)

Publicly available charts from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections depict trends in parole hearings, grants, deferrals and denials. The number of people granted parole in Wisconsin has increased since last year but has decreased overall since 2017. (Source: Wisconsin Department of Corrections)An average of 37 people were granted parole in 2023 and 2024, compared with an average of 144 a year from 2017 to 2022, the data show.

From Jan. 1 to Aug. 31 of 2025, there have been 234 parole hearings for people convicted in Milwaukee County. Out of these, 19 people were granted parole, 201 were deferred and 14 were denied.

As of Aug. 31, 43 people had been granted parole in Wisconsin in 2025, out of 551 hearings.

Williams hopes to add his name to the list of people granted parole, but that is still in question.

'Not an entitlement'

A spokesperson for the Wisconsin Parole Commission said in an email to NNS that a parole is “not an entitlement.” He said all five parole requirements must be met, including reducing the risk someone poses to the public and that a person has served enough time.

He said risk reduction is determined using several factors, including sustained good conduct, completion of required programming, transition through lower security levels and the approval of their release plan.

“This requirement is met when the risk to the public upon release is considered not unreasonable,” the spokesperson said.

For time served, the commission spokesperson said the requirement is met “when the amount of time served is sufficient to not diminish the seriousness of the original offense.”

Red tape?

Williams, whose next parole hearing is scheduled for January, disputes the commission’s assessment. Nevertheless, he is trying to follow its guidance leading up to his next hearing.

Williams said this is easier said than done, given the lack of clarity about parole.

Williams said he is also worried about being deferred again because of a lack of coordination within the Department of Corrections.

After his most recent parole hearing in June, commissioners endorsed a transfer for Williams to a less restrictive facility – called a Wisconsin Correctional Center System facility – where he would be able to participate in work release.

Programming and activities at these facilities place an emphasis on life after release and only house people requiring minimum security.

About a month after his June parole hearing, the Program Review Committee at Oakhill could not reach a consensus on whether to transfer Williams, according to paperwork he received from Oakhill staff.

Derek Williams was transferred from Oakhill Correctional Institution in September. (Michelle Stocker / The Cap Times)

Derek Williams was transferred from Oakhill Correctional Institution in September. (Michelle Stocker / The Cap Times)After learning of the split decision, Rikki Williams, Derek’s wife, raised their concerns to Jason Benzel, director of the Department of Corrections’ Bureau of Offender Classification and Movement.

In an email, Benzel told Rikki to “be patient and allow the process to occur.”

She then contacted Jared Hoy, secretary of the Department of Corrections.

“I understand your frustration, I really do,” Hoy wrote in an email to Rikki. “If we cut corners for Derek and rush the process, or if I intervene and put my thumb on the scale, that would not be fair to the many, many others who go through a similar process.”

These explanations ring hollow for Rikki.

“Everyone tells us to ‘trust the process,’ ” Rikki said. “What process?”

Rikki Williams sits in bumper to bumper traffic during an hourlong drive to see her husband, Derek Williams, at Sturtevant Transitional Facility on Oct. 2, 2025. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)

Rikki Williams sits in bumper to bumper traffic during an hourlong drive to see her husband, Derek Williams, at Sturtevant Transitional Facility on Oct. 2, 2025. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)Recent progress for Williams

Wayne Olson, the warden at Oakhill, and another Department of Corrections administrator reviewed the Program Review Committee’s split decision on Williams’ transfer. They approved a transfer but not to a Wisconsin Correctional Center System facility.

Instead, on Sept. 16, Williams arrived at Sturtevant Transitional Facility, which houses people requiring minimum or medium security.

Olson and the DOC administrator chose Sturtevant because it can provide a more “gradual transition” from Oakhill, according to the paperwork.

Rikki Williams and her mother, Donna Woodruff, walk into Sturtevant Transitional Facility to visit Rikki's husband, Derek Williams, on Oct. 2, 2025. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)

Rikki Williams and her mother, Donna Woodruff, walk into Sturtevant Transitional Facility to visit Rikki's husband, Derek Williams, on Oct. 2, 2025. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)Off-site employment is available at Sturtevant, the paperwork stated, "at the discretion of the warden," and requires a "period of monitoring on-site."

As Williams waits in limbo, he often returns to a particular irony.

“I made a life-or-death decision in a heartbeat,” he said. “But it’s taken years for anyone to decide what to do with my life.”

Rikki Williams talks with Derek Williams over a video call. Rikki has been waiting for her husband to be paroled since 2023. “I think I got overly happy thinking he was coming home right away,” she said. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)

Rikki Williams talks with Derek Williams over a video call. Rikki has been waiting for her husband to be paroled since 2023. “I think I got overly happy thinking he was coming home right away,” she said. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)Jonathan Aguilar is a visual journalist at Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service who is supported through a partnership between CatchLight Local and Report for America.