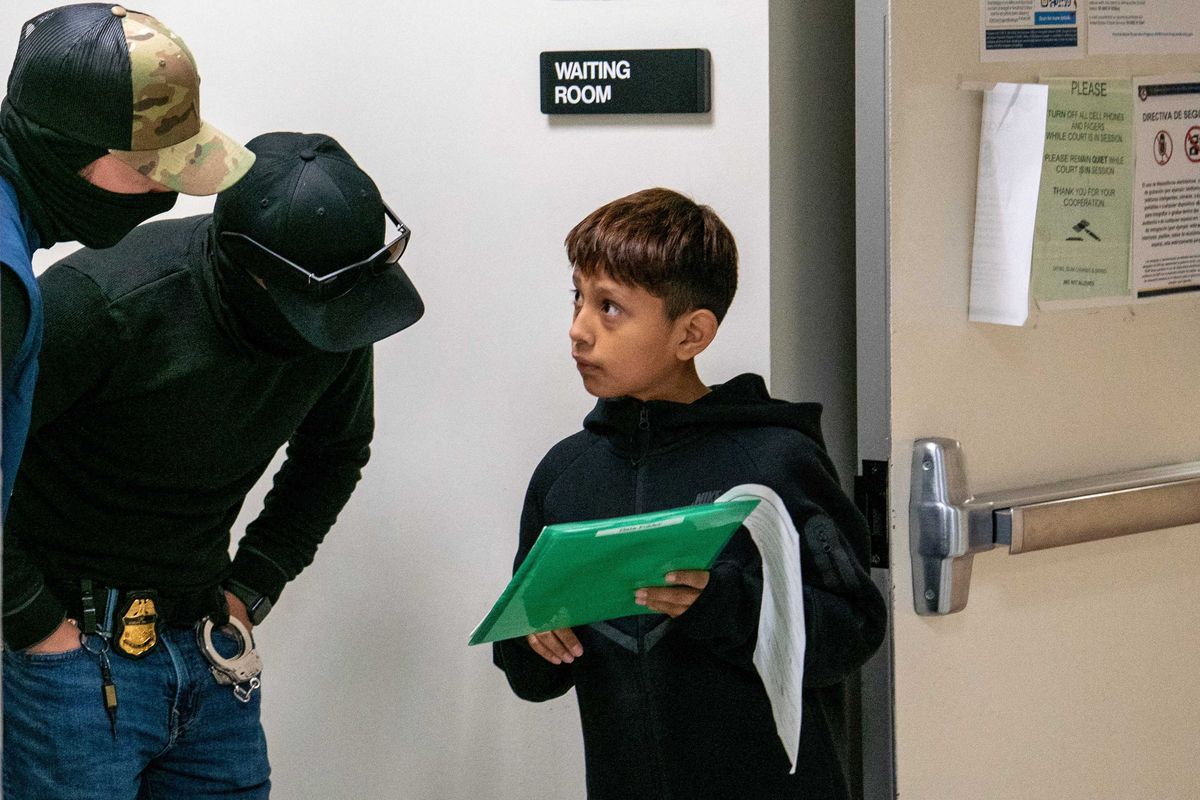

Five-year-old Luz spent 72 days separated from her father, Julio Rodriguez, after they were detained at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2018.

Escaping extortion and violence in Guatemala, Julio was detained in Texas while Luz was sent to a shelter in New York. Eventually, they reunited in Atlanta and joined family in Massachusetts.

Melanie Hernandez left Guatemala in the middle of the night in 2019 with her 14-year-old son, Lucas, fleeing an abusive husband. She left behind an adult daughter and five-year-old son with severe heart disease. Melanie spent several days away from Lucas when detainees were separated by gender at the U.S. border.

The Rodriguez and Hernandez families are just two of 16 that experienced family separation under the first Trump administration, and who are now the subjects of a book by Gabrielle Oliveira, Now We Are Here: Family Migration, Children’s Education, and Dreams for a Better Life.

The families from Brazil, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador all came to the U.S. with children, the youngest four months old. Some mothers were pregnant.

The parents and children faced significant trauma that lingers though they are settled in the U.S., pursuing asylum cases, Oliveira writes.

Oliveira observed the children in school as much as twice a month over two to three years.

Gabrielle Oliveira (provided photo)

Gabrielle Oliveira (provided photo)

She observed families at home and engaged in communities, from meetings with lawyers to trips to the grocery store and church, for more than 2,500 hours. She interviewed parents and some children twice a month.

“I think if we have children as our North Star for policymaking, it would change everything,” Oliveira, a Harvard professor, told Raw Story.

‘More tragedy’

From being mugged to paying bribes, the families encountered numerous dangers on their way to the U.S., Oliveira writes.

One family traveled in a windowless truck with 50 other people, including babies, pregnant women and elderly folks.

Julio Rodriguez paid a smuggler $7,000 to help him and Luz get to the U.S., traveling for 12 days from Guatemala to Ciudad Juárez in Mexico.

Diana López, from Guatemala, recalled crossing the Rio Grande with her two-year-old in her arms. When her daughter fell into the river, Lopez grabbed her from underwater.

López told Oliveira: “When I was leaving the water with Belén in my arms I was relieved that we survived the river … But when I looked up what I saw were these electric pistols … the next thing I know I felt it in my arm, stinging, and I fell to the ground.”

"Now We Are Here" book cover

"Now We Are Here" book cover

While the parents were often fleeing unsafe situations, the ultimate motivation in risking all to cross the border came down to seeking better education for their children, Oliveira writes.

Melissa Santos, a mother from Brazil, told Oliveira: “It’s one of those things: do you stay and let your children not have a chance, become drug addicts, and get shot by a stray bullet, or do you travel north and risk being arrested, shot, and deported. It’s more the same … more tragedy.”

‘Did I make a mistake?’

Oliveira learned that many parents questioned whether the trek was worth it, then found themselves separated and exposed to inhumane treatment after reaching U.S. soil.

The families encountered another hurdle: COVID-19, which stopped children attending school in person.

Julio told Oliveira how he would comfort Luz, who was missing her mom and home: “I used to tell her about the good life we would have and that she would not believe the schools … I was just trying to have her not be sad all the time … But I kept thinking about the mistakes I made … Did I make a mistake bringing her?”

Oliveira, who immigrated to the U.S. herself, from Brazil, said parents saw children having nightmares, seeming detached, or struggling in school.

Some parents were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder but had to keep moving forward.

"That's why the title is Now We Are Here,” Oliveira said.

“The counter mantra to the ‘What if, what if, what if, what if’ is ‘Now we're here,’ so this is the shot that we have. That kind of stabilized the doubts of being worthy or not.”

‘They're going to grow up with this trauma’

President Donald Trump was in the White House for his first term when the 16 families came to the U.S.

With the second Trump administration employing even harsher immigration enforcement tactics, Oliveira imagines families such as those she writes about now being unable to reach the U.S.

“So many of them were escaping life-and-death moments, so not being able to ask for asylum, not being able to do that, I think it would be extremely, even more dangerous than what it was a few years ago, just because of how the border is right now,” Oliveira said.

With the Trump administration aggressively detaining and deporting immigrants — and encouraging unaccompanied children to self-deport — Oliveira said another form of family separation is happening.

“It's going to be forever with them. They're going to grow up with this trauma, and it's not an easy one to address,” she said.

Oliveira has stayed in touch with those she interviewed. Some, she said, have been afraid to leave their homes for doctor’s appointments, psychological treatment or speech therapy, due to the wave of deportations and detentions.

“It was a real chilling effect,” Oliveira said.

Still, the children she followed remained in school, with six teens having graduated high school.

Oliveira has mixed feelings about her book being published at this moment.

“I'm happy that at least there are these stories in this moment right now, and they're needed,” she said.

“Let's think about the well-being of children. We can come together on this one.

“It also makes me nervous … that it could be misplaced or misused, or in any of these ways that it wasn’t intended … the moment that we're living, it's a delicate one to tell stories."