CAL State San Bernadino design major Nohemi Gonzalez saved enough money to live her dream of studying in Paris for a semester.

On November 13, 2015, the college senior met friends for dinner in the 11th arrondissement — a neighborhood known for edgy art and racial and religious diversity. As diners applauded the staff at La Belle Équipe, who brought a birthday cake to a waitress at 9:30 p.m., a dark car stopped nearby. Soon after, two heavily armed men emerged and blasted the candlelit tables with gunfire. In less than three minutes, 19 were dead. One of those killed was Nohemi.

Across Paris, ISIS shooters and a suicide bomber attacked a popular bar, a Cambodian restaurant, a nightclub concert, a sports stadium and La Belle Équipe. The terrorists killed 130 people.

Investigators later learned that some attackers were recruited by an ISIS video posted on YouTube. Noemi's family sued Google, which owns YouTube, after learning from investigators that the men clicked on a link to the video after YouTube recommended it as content they might enjoy. The U.S. Supreme Court will hear Gonzalez v Google on February 21.

But Twitter, Google, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and other social media giants have powerful protection from such liability thanks to Section 230(c)(1) of the Communications Decency Act.

Created in 1996, Section 230 states that social media are neutral tools offering recommendations based on an online visitor's usage, not distinguishing between moral and immoral content.

"Platforms are encouraged to voluntarily block and screen objectionable content; however, they are granted immunity if they do not," explains Bipartisan Policy Center analyst Sabrina Neschke.

But Section 230 was crafted in the internet's infancy, long before Artificial Intelligence and other revolutionary tech advances enabled algorithms to guide users into the darkest corners of the web. Soon, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments about whether Section 230 still fits the sophisticated, AI-enhanced algorithm that social media uses in 2023.

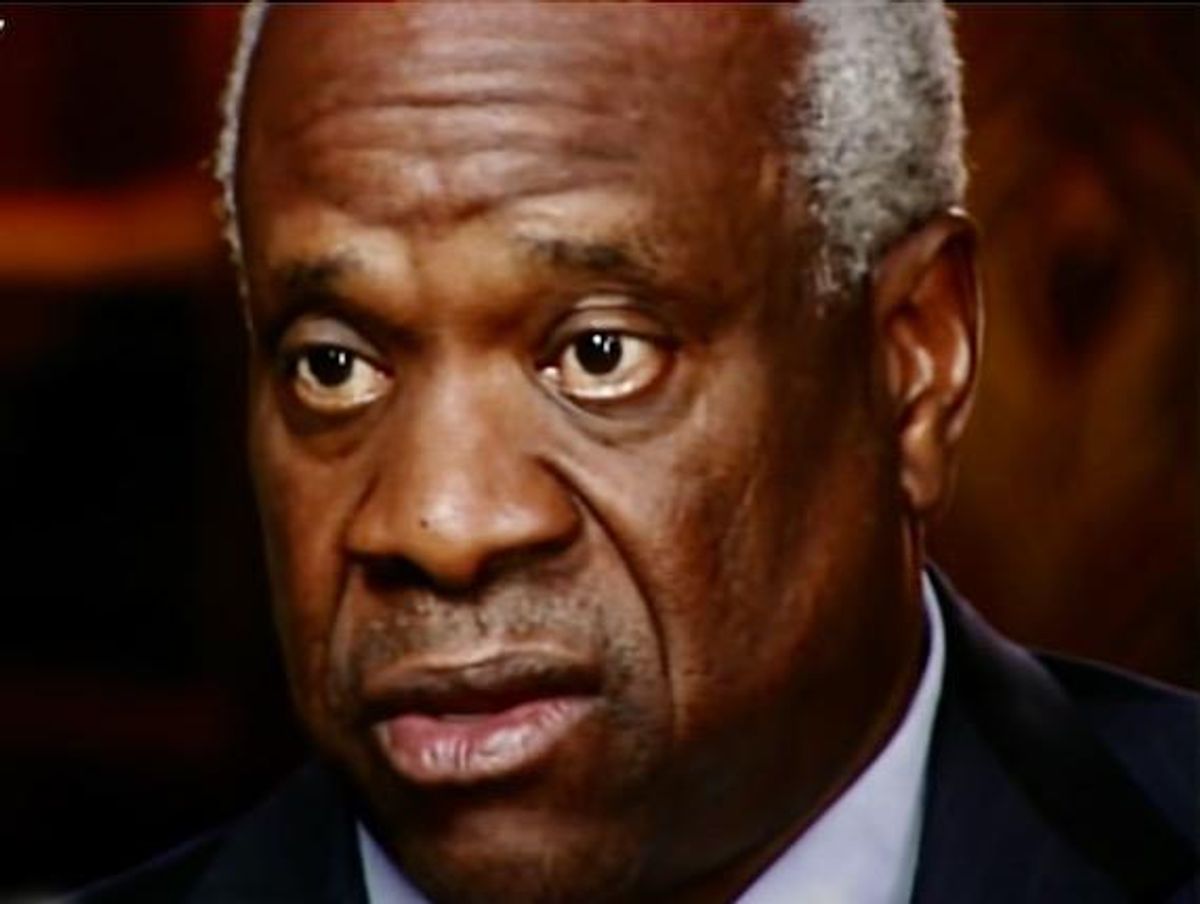

Interestingly, Justice Clarence Thomas, whose wife became well-known for posting debunked conspiracy theories about the 2020 presidential election, urged SCOTUS to tackle the question.

"Thomas has previously voiced skepticism toward Section 230," Neschke wrote. "Thomas expressed dissatisfaction with the Supreme Court’s decision to not further review (last year's) Jane Doe v. Facebook, Inc., stating, “Assuming Congress does not step in to clarify 230’s scope, we should do so in an appropriate case."

Jane Doe v Facebook Inc. resulted when an adult male predator befriended a girl, 15, via Facebook and convinced her to meet him. He raped, beat and sexually trafficked her. Jane Doe argued that Facebook was liable for violating anti-sex trafficking laws.

People for the American Way's Supreme Court analyst is attorney Elliot Mincberg — a former House Judiciary Committee chief counsel for oversight and investigations. He told Raw Story this is a possible landmark case for social media platforms.

"This case is nuanced and complex," Mincberg said, adding that it's also more unpredictable since it won't trigger "the break along conservative and moderate justices that you see with cases involving LGBTQ rights or guns."

There has been surprisingly broad bipartisan support for getting Gonzalez v. Google heard in America's highest court. Trump loyalist Sen. Josh Hawley and the Biden Justice Department filed briefs urging SCOTUS to consider Gonzalez's position.

The Justices' decision could dramatically alter the social media landscape.

Section 230 allowed a new form of communication to evolve by shielding social media platforms from endless lawsuits from online visitors who disliked some content. Mincberg condenses Section 230’s protective message: “Don’t blame Google, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, etc., because they are only messengers.”

Gonzalez family attorney, Keith Altman, argues that today's robust tech giants are obliged to take more responsibility for the content they recommend and showcase.

"By their terms of service...on YouTube, you have to submit your articles for monetization to Google," Altman told NBC News. "Then they start putting ads on our pages and sharing revenue with you."

The National Association of Attorneys General's Dan Schweitzer explains that the Gonzalez family's lawsuit argues that algorithms are no longer neutral tools but more like the human book or film reviewers who analyze then recommend content.

"They argue that Google’s allowing the content to be posted on its website and recommending the content are two separate acts, and only a lawsuit based on the former would seek to treat Google as a publisher and thus entitle it to immunity," he wrote. "Petitioners also point out that the recommendations are not themselves a communication from a third party but rather are from the interactive service itself."